Financial Markets’ Complacency is About to Be Tested

-

February 12, 2025

DownloadsDownload Article

-

Well, that didn’t take long. Less than a week into his second term, President Trump has already put the global order on notice that the U.S. role in the global economy will be changing. Nobody should be surprised by that.

The timing of the 2025 World Economic Forum (“WEF”) in Davos could not have been better for him and provided a megaphone directed at the global economic elite gathered there. “Come make your product in America and we will give you among the lowest taxes of any nation on earth,” he said. “But if you don't make your product in America, which is your prerogative, then very simply, you will have to pay a tariff.”1 (Rough translation: Nice car industry ya got there. Would be a shame if anything happened to it.) How much of this tough talk is a negotiating tactic and how much is a sneak preview of policy changes to come remains to be seen, but President Trump surely has everybody’s attention. New import tariffs on our three largest trading partners have just been announced.

It also took President Trump little time to throw down the gauntlet at Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s feet — which we predicted two months ago, but it was so foreseeable we can’t brag about it. Speaking via video at the WEF, President Trump commented, “I’ll demand that interest rates drop immediately. And likewise, they should be dropping all over the world. Interest rates should follow us all over.”2 (Note the use of the word “demand” here.) President Trump is spoiling for a fight with Fed Chair Powell to prime the pump even though the current domestic economic backdrop does not warrant aggressive monetary easing. The consensus market expectation is for just two Fed rate cuts in 2025, as the labor market remains strong, inflation is proving pesky, and financial markets are getting silly. A strong domestic economy combined with import tariffs and unnaturally low interest rates will be inflationary. Few credible economists debate this likely outcome. Within two weeks of demanding lower interest rates immediately, President Trump backtracked and endorsed the Fed’s decision not to lower the Fed Funds rate in January.3

President Trump went further to antagonize Fed officials, saying later that day in the Oval Office, “I think I know interest rates much better than they do, and I think I know it certainly much better than the one who’s primarily in charge of making that decision.”4 Ouch. Recall that back in 2019, President Trump advocated for the same zero or negative interest rates here that prevailed in some troubled countries and regions that were fighting economic stagnation or contraction.5 He thought a zero interest rate was great policy even for an economy that was experiencing respectable growth. President Trump has also questioned the need for an independent Federal Reserve, saying the president should have at least some say in monetary policy decisions.6,7 Jawboning the Fed is one thing — it has been done by presidents for decades, including President Trump in 2019 — but giving the president any degree of direct control over monetary policy is crossing a bright line that has been in place since the Federal Reserve System was created in 1913.

So credit markets may be a tad nervous about Trump’s recent threats despite Chair Powell’s insistence that political considerations and external pressure will not influence Fed policy decisions. Perhaps it will turn out that way, but Powell’s term expires in 2026, and we know how that will play out if he doesn’t acquiesce. Yes, very low interest rates are a nice thing, and so are stock markets that always go up and energy prices that are always low. But these outcomes cannot be imposed without consequence. Ultimately, market forces make these determinations.

The Fed has great influence over short-term interest rates, but Treasury note and bond rates and all other rates that key off of them are made in credit markets — and those traders and investors aren’t captive to the whims of the most powerful man in the world. In fact, long-term Treasury yields ticked slightly higher immediately after these comments from President Trump. The Fed and its policy decisions can influence interest rates, but Treasury markets will determine the long-term cost of U.S. borrowing, and they are expressing some concern.

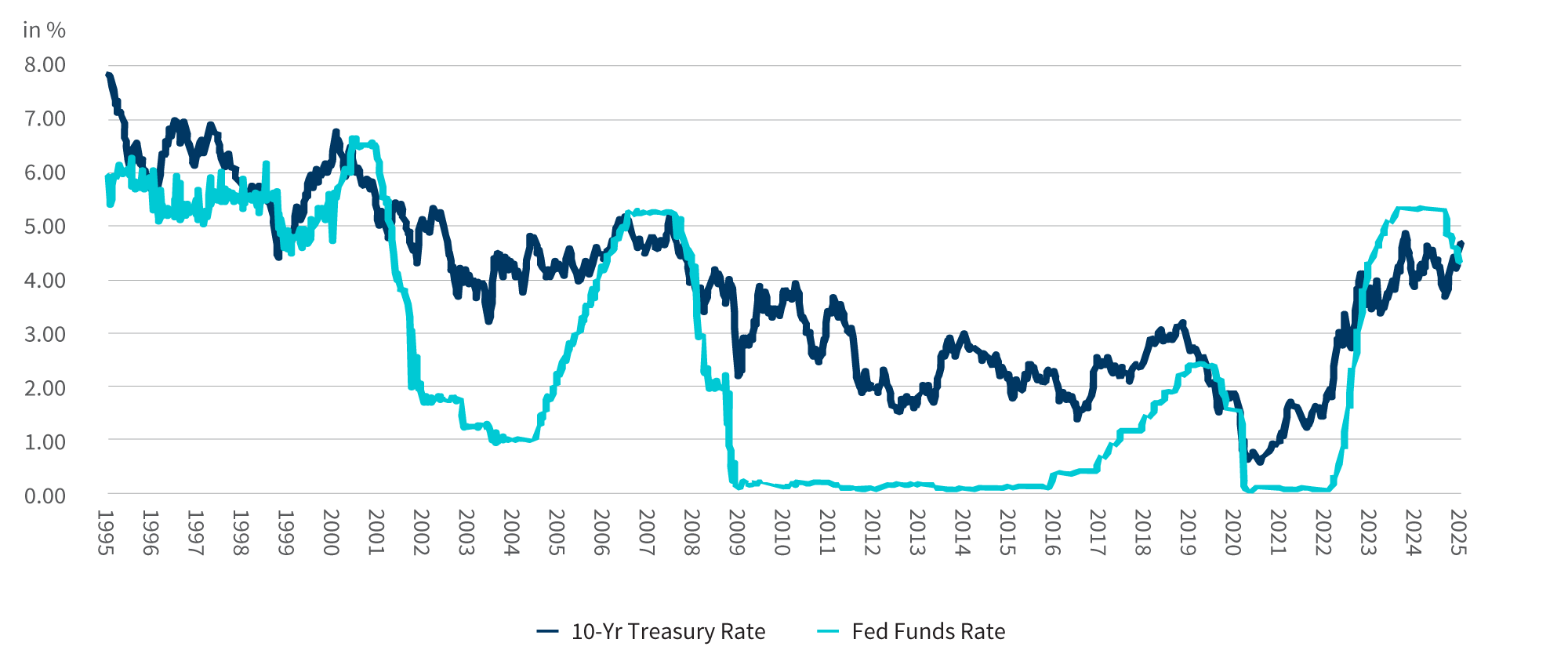

There have been four distinct episodes of Fed rate cutting since 1995 (Figure 1), including the current one, and so far this is the only one where Treasury rates have moved higher as the Fed Funds rate moved lower, though it is still too soon in this cycle to reach any conclusion. As we pointed out last month, the 10-year Treasury note yield is 90 bps higher than in September, when cumulative Fed rate cuts of 100 bps began. There is no modern precedent for this divergence.

What is the significance of this development? Credit markets are apprehensive about an upturn in inflation, especially with some of the stimulative economic policy ideas floated by President Trump. Secondly, markets are wary of soaring federal budget deficits that have become so large in absolute and relative terms since 2020 (with an expanding economy, no less) that they cannot be ignored any longer. Lastly, credit markets recall that President Trump had little regard for taming budget deficits in his first term, with deficits climbing each year of his presidency and doubling by 2019 compared to 2015 — again, while the economy was growing.

Credit markets now seem unwilling to turn a blind eye to our deeply imbedded fiscal imbalances, with Treasury yields edging higher since late 2024. Some respected market commentators are expecting “a 5-handle” on the 10-year Treasury yield in 2025, a rate range that wasn’t considered an outlier prior to 2000 but must seem unreal to a younger generation of Wall Streeters who have known nothing but a highly managed interest rate environment since 2009. That was unreal. A showdown between President Trump and the Fed, should it materialize in 2025, will be fascinating to watch —“must see TV” as they used to say.

Figure 1 – 10-Year Treasury Rate vs. Fed Funds Rate

Source: FRED, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Leveraged Credit Markets Showing Little Concern Over Lofty Loan Default Levels

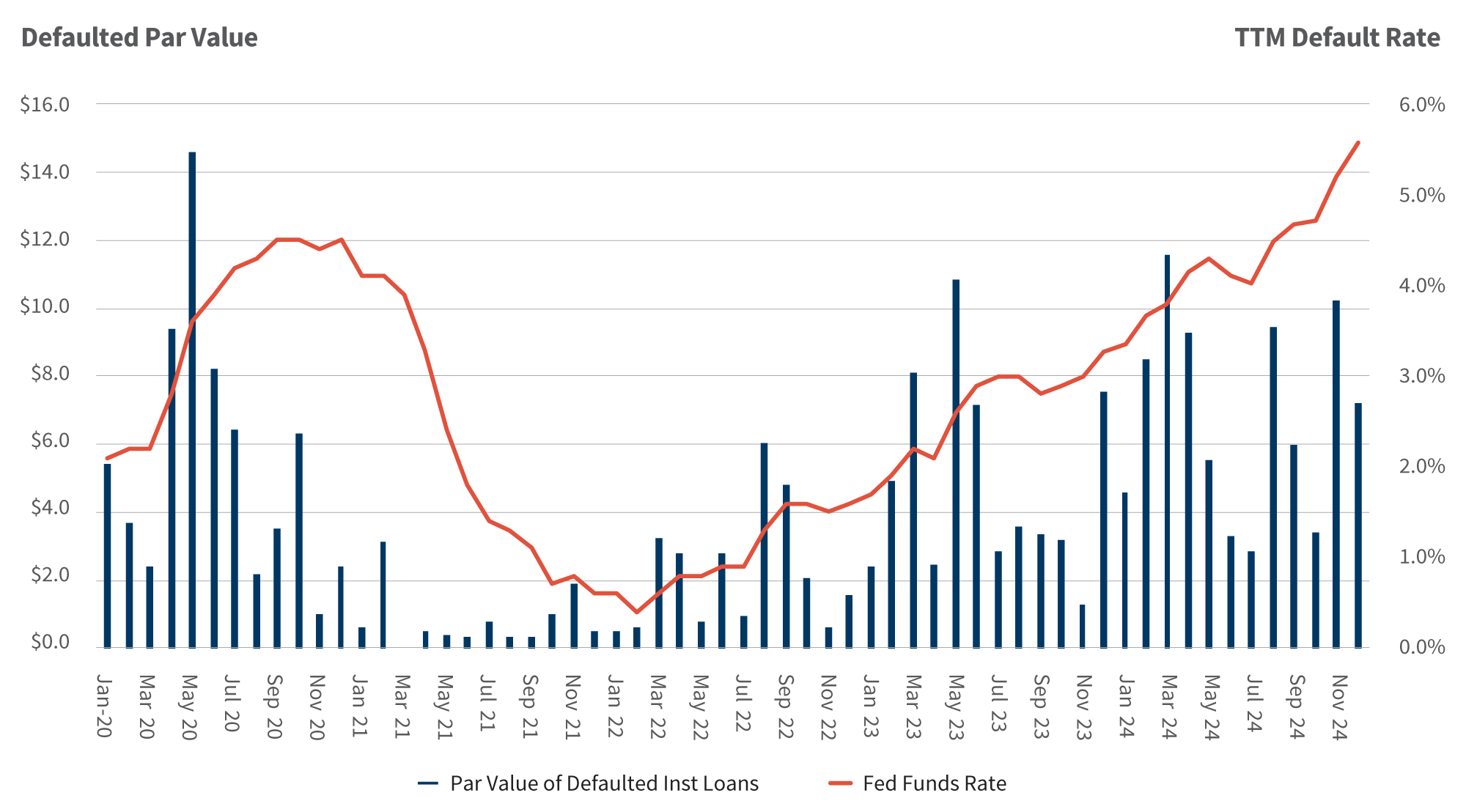

The prevailing theme in leveraged loan markets last year was record levels of issuance amid a refinancing bonanza, and the issuance party has shown little sign of slowing so far in January. Leveraged credit markets are in full risk-on mode that is expected to continue in 2025. What has gotten much less attention in the business media and little concern from lenders is the large upswell of leveraged loan defaults last year. Fitch Investors reported $82 billion of U.S leveraged loan defaults in 2024 compared to $55 billion in 2023.8 Moreover, the U.S. leveraged loan default rate (which Fitch measures by dollar volume) ended the year at its peak of 5.6%, higher than the COVID peak of 4.5% in 2020; it was 3.3% at the end of 2023 (Figure 2). This far exceeded expectations going into last year. Fitch Ratings initially forecasted a U.S. leveraged loan default rate of 3.5%–4.0% for 2024, which it later revised at midyear to 5.0%–5.5% as defaults piled up.

Why the lack of concern or circumspection from lenders? There are a couple of reasons. Primarily, 55 of 93 large loan defaults (59%) in 2024 were distressed exchanges compared to 30 of 71 defaults (42%) in 2023.9 By dollar volume, $58 billion of $82 billion in defaults (71%) were distressed exchanges compared to 39% in 2023. In other words, missed payments and Chapter 11 filings collectively made up a minority of default events last year. This is consistent with S&P, which reported that 54% of default events globally in 2024 (measured by number, not dollar volume) were distressed exchanges, its largest annual share of defaults this century. It is no secret why this is happening: CreditSights recently reported 43 domestic transactions in 2024 that it considered to be liability management transactions (“LME”) compared to 31 in 2023.10

Figure 2 – U.S. Leveraged Loan Default Rate

Source: LSEG LPC, Distressed Market Review, December 2024

Apparently, the leveraged lending community is content to view LMEs as a bridge to better times, a preemptive protective measure, or anything other than a slow-motion restructuring that many LMEs will turn out to be. Thus, LMEs are not considered “real defaults” in the minds of many lenders, especially if they are on the right side of those deals, and so they remain mostly undeterred by rising loan default totals attributable to these transactions. More cynically, many leveraged lenders may realize that if they want to be doing business with larger PE sponsors — the primary authors of weak loan documentation that make LMEs possible — they will have to accept these borrower-friendly terms and their potential consequences as the price of admission.

Our upcoming 2025 Leveraged Loan Market Survey supports this premise. For all the talk of “blockers” and other stricter provisions now being written into loan documents, nearly a majority of our respondents said that loan documentation in recent deals provides no stronger lender protections (24%) or fewer lender protections (23%) than those in deals where LMEs have been completed, while 47% said recent deals provided only modestly stronger lender protections. These responses were highly consistent among traditional bank lender respondents and non-bank lenders. So the parade of LMEs likely will continue, perhaps unabated. It might require double-digit loan default rates before we see heightened concern and significant pushback from lenders. Until then, many leveraged lenders will be content to keep whistling to the tune of “Don’t Worry, Be Happy.”

Footnotes:

1: David Lawder, Susan Heavy, “Trump to Global Firms: Manufacture in USA or Face Tariffs,” Reuters (January 23, 2025).

2: Jeff Cox, “Trump Says He’ll “Demand That Interest Rates Drop Immediately”,” CNBC (January 23, 2025).

3: Jeff Cox, “In a Switch, Trump Approves of the Fed’s Decision to Hold Interest Rates Steady,” CNBC (February 3, 2025).

4: Skylar Woodhouse, “Trump Says He Knows Interest Rates Better Than Fed Chief Powell,” Bloomberg News (January 23, 2025).

5: Howard Schneider, “Trump Reverses Course, Seeks Negative Rates from Fed ‘Boneheads,’” Reuters (September 11, 2019).

6: Elisabeth Buchwald, “The Federal Reserve As We Know It Could Soon Be Turned on its Head,” CNN Business (November 6, 2024).

7: Jordan Weismann, “Could Donald Trump Break the Fed?,” The Atlantic (August 21, 2024).

8: “Distressed Market Review,” LSEG LPC (December 2024).

9: Ibid.

10: “US Liability Management Transactions: Quarterly Update Through 4Q 2024,” CreditSights (January 14, 2025).

Related Insights

Published

February 12, 2025

Key Contacts

Key Contacts

Global Chairman of Corporate Finance

Downloads

Most Popular Insights

- Beyond Cost Metrics: Recognizing the True Value of Nuclear Energy

- Finally, Pundits Are Talking About Rising Consumer Loan Delinquencies

- A New Era of Medicaid Reform

- Turning Vision and Strategy Into Action: The Role of Operating Model Design

- The Hidden Risk for Data Centers That No One is Talking About