- Accueil

- / Publications

- / Articles

- / The Art and Science Behind Damages in Investment Management Disputes

The Art and Science Behind Damages in Investment Management Disputes

-

5 décembre 2024

TéléchargezDownload Article

-

Reproduced with permission from Law Business Research Ltd. A previous version of this article was published in November 2022 and can be found here: https://globalarbitrationreview.com/review/the-european-arbitration-review/2023/article/art-and-science-behind-damages-in-investment-management-disputes

Summary

Disputes between investors and investment managers typically arise from allegedly unsuitable investment decisions that lead to financial losses. Although calculating reliable damages figures in the context of investment management disputes can be challenging in retrospect, there exist techniques to inform counterfactual investment decisions and estimate damages without being overly influenced by which investments have turned out to be profitable and which have not.

The investor’s risk profile (‘IRP’) and the agreed investment mandate are central to determining suitability, with factors such as financial circumstances, risk tolerance and investment goals which guide the investment mandate. This analysis can be complex when so-called ‘alternative investments’ are considered, such as investments in private companies, art, and so on. Such assets are harder to value than traditional asset classes such as listed shares, but can enhance portfolio diversification and performance.

The “low-risk anomaly” shows that low-risk portfolios can sometimes outperform high-risk ones, especially over certain timeframes, confirming that higher risk does not always lead to higher returns.

The Multidimensional Nature of Investment Management Disputes

Investment suitability claims usually arise when investors, typically having sustained losses on their investment portfolio, bring claims against their investment manager or adviser because their investment exposed them to risks which they had not understood or which did not align with their expectations.

Experts are typically asked to assess whether the investments were unsuitable and, if so, which alternatives would have been suitable and how they would have performed. This exercise can also involve investigating whether regulatory obligations were fulfilled, if fraud occurred, whether the overall portfolio construction was suitable and if the investment manager or adviser took all necessary steps to meet the investor’s risk profile.

Investment management disputes can be multidimensional and key considerations are case-specific, such as the allegations made, market context, regulation, investment period, investor type and profile, technicalities regarding financial instruments and factual evidence. Whilst investment management requires precision, and quantitative, statistical, economic and mathematical tools exist to measure risks, advice on the appropriateness of an investment can require a level of judgement after taking account of a variety of considerations.

While investment management experts can opine on market practice and matters to inform conduct and effectively assist courts with liability or causation issues, we focus below on the assessment of damages.

So, what are the primary challenges when calculating damages in investment management disputes? How can empirical evidence help in constructing a counterfactual investment portfolio? What role do investment risk profiles and mandates play in creating a suitable investment portfolio?

Finding the Right Comparator: Avoiding the Risk of Hindsight

One of the main challenges experts face when asked about the quality of an investment manager’s investment decisions or when formulating a counterfactual investment portfolio is to avoid hindsight. When constructing investment portfolios, investment managers have no choice but to make decisions based on information available to them at the time. One of the simplest and most common approaches for producing a suitable counterfactual investment portfolio for calculating damages is to rely on empirical evidence of comparable investment portfolios. This is because empirical evidence provides information about the outcome of real investment decisions made ex ante by a universe of investment managers at a particular point in time, without the benefit of hindsight. These real-world investment decisions are much more objective and reliable, when looking at the make-up and performance of a counterfactual portfolio, than attempting to step into the shoes of an investment manager and building in retrospect a theoretical portfolio that ignores the uncertainty an investment manager faces when making investment decisions.

Investment managers compete and have different views, so portfolio composition can vary significantly even across funds with similar investment mandates. When selecting fund managers within a comparable universe, investors effectively have the choice among a range of suitable portfolios. This investment universe offers a distribution of returns for a given level of risk over a given investment horizon and allows investors to rank the performance of fund managers and separate those who outperform their peer group from those who achieve an average or below-average return.

Because there is a range of possible outcomes for any suitable investment mandate, observing that a portfolio underperformed after the fact would not be sufficient to determine whether an investment was suitable for an investor at the outset as a suitable investment can still result in losses. Therefore, the portfolio components and other criteria, including fees, trade execution, concentration and leverage, should be assessed in light of the IRP and the agreed mandate. Depending on the findings, damages may only apply to certain component parts of the portfolio or the portfolio as a whole.

Investor Risk Profile and Mandate

Assessing an IRP is a judgemental process, given the subjective nature of the IRP process. It depends on:1

- The investor’s circumstances: personal information such as age and familial situation, level of education, nationality, country of residence, professional situation, other banking relationships, net wealth and liabilities.

- The proportion of wealth invested and purpose: this is needed to assess the size of the managed portfolio relative to an investor’s total wealth and any financial or tax planning associated with the investment portfolio – such as wealth preservation, capital growth, regular lifestyle income, retirement income and inheritance.

- The investor’s knowledge and experience: an investor’s ability to make informed investment decisions, when advised or on their own, is typically assessed by asking investors to answer questions such as how frequently they have invested in particular instruments, how long they have used wealth management services and how knowledgeable they assess themselves to be regarding the risks associated with particular investments or wealth management services.

- The investor’s risk and return objectives: the desired level of return and appetite for downside risk, the type of return and the investment horizon and liquidity needed. Although some investors will consistently express the same IRP over time and across their wealth management relationships, not all investors do. As a result, IRPs need to be reassessed regularly.

Based on their understanding of an IRP, investment managers define the portfolio mandate in agreement with the client. Although assessing IRPs may satisfy some regulatory hurdles, there are no specific guidelines for how these should align with the framework for setting up investment mandates.2 Investment mandates usually operate under three generic relationship types – execution only, advisory and discretionary mandates.

In investment management disputes, the parties often disagree on the level of risk of the investment mandate. But defining an investment mandate solely by reference to its level of risk does not provide the expert with sufficient information about the counterfactual portfolio. There is no single source of truth defining how exactly the mandates composing an investment portfolio should align with a given IRP. However, there is a broad consensus regarding the various criteria to be considered when framing an investment mandate, such as:

- Investment theme: investing in a specific, or across various, geographies, sectors, industries and market segments.

- Currency risk: the reporting currency of the investment mandate, the currencies allowed for underlying investments and the ability to hedge currency risk.

- Investment restrictions: defining a set of eligible investments such as floating rate notes only or the ability to employ leverage.

- Limits: concentration by issuer, counterparty, rating, geography, industry, currency or maximum leverage that can be employed.

- Tolerance levels: when a position should be rebalanced if it exceeds a limit or if a previously eligible investment breaches an investment restriction.

- Investment strategy: generating fixed income or growth returns, favouring capital protection over capital at risk or choosing between active or passive investment.

- Investment horizon: depending on the short, medium or long term.

- Performance hurdles and manager’s remuneration: referring to a target return or benchmark the mandate should target or outperform, and the investment manager remuneration and/or performance fees.

Although experts can provide technical assistance for courts to understand the extent to which an investment portfolio complied with the agreed investment mandate and IRP, the agreed investment mandate and IRP remain largely a matter of factual evidence. Disclosure about the information a wealth manager relies on to understand an IRP and the nature and composition of the investment mandate is key.

Portfolio Construction and Asset Allocation

Traditional Versus Alternative Investments

A portfolio is efficient if it maximises the expected return for a given level of risk. In modern portfolio theory, the universe of portfolios that satisfy this condition occupy what is known as the efficient frontier.3

Historically, traditional asset classes such as stocks, bonds and cash have been the primary tools used to build a diversified portfolio. Increasingly, alternative investments (‘AIs’) such as hedge funds, private debt and private equity, venture capital, structured products, cryptocurrencies and art have made their own space in portfolio asset allocation.

Unlike traditional investments, AIs may come with higher minimum investment amounts and complex fee structures, which can make them less accessible to some investors. AIs may be illiquid or may not have a secondary market available, making it more challenging to estimate their value. AIs may not be as regulated and standardised as traditional investments, which can open investors to additional risks.

On the other hand, AIs can provide exposure to sources of risk and returns that are not seen with traditional asset classes, giving them the potential to enhance portfolio returns. As a result, adding AIs to a portfolio can enhance the efficient frontier relative to a portfolio composed exclusively of traditional assets.4

AIs are – in principle – suitable investments if invested in the right proportion as part of a broader portfolio. They can suit various risk profiles, ranging from very low to very high-risk portfolios. Because of their diversification benefits, the proportion of AIs in diversified investment portfolios tends to decrease as risk increases.

Additionally, it has been noted that the proportion of AIs in an investment portfolio increases with wealth,5 highlighting the importance of considering an investor’s circumstances and ways in which wealth broadens the investment universe and might affect the composition of an investment portfolio.

Risk Versus Performance

The difference between high- and low-risk investments is often misunderstood.

As defined by the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority:

There is clear empirical evidence that high-risk investments do not consistently perform better than low-risk investments and that the relative performance between higher and lower risk depends on the observed timeframe. This is known as the concept of the ‘low volatility anomaly’ or the ‘low-risk anomaly’, which contradicts theories that higher risk portfolios earn higher returns. For example, between January 1968 and December 2008, low volatility and low beta portfolios have offered an enviable combination of high average returns and small drawdowns.7

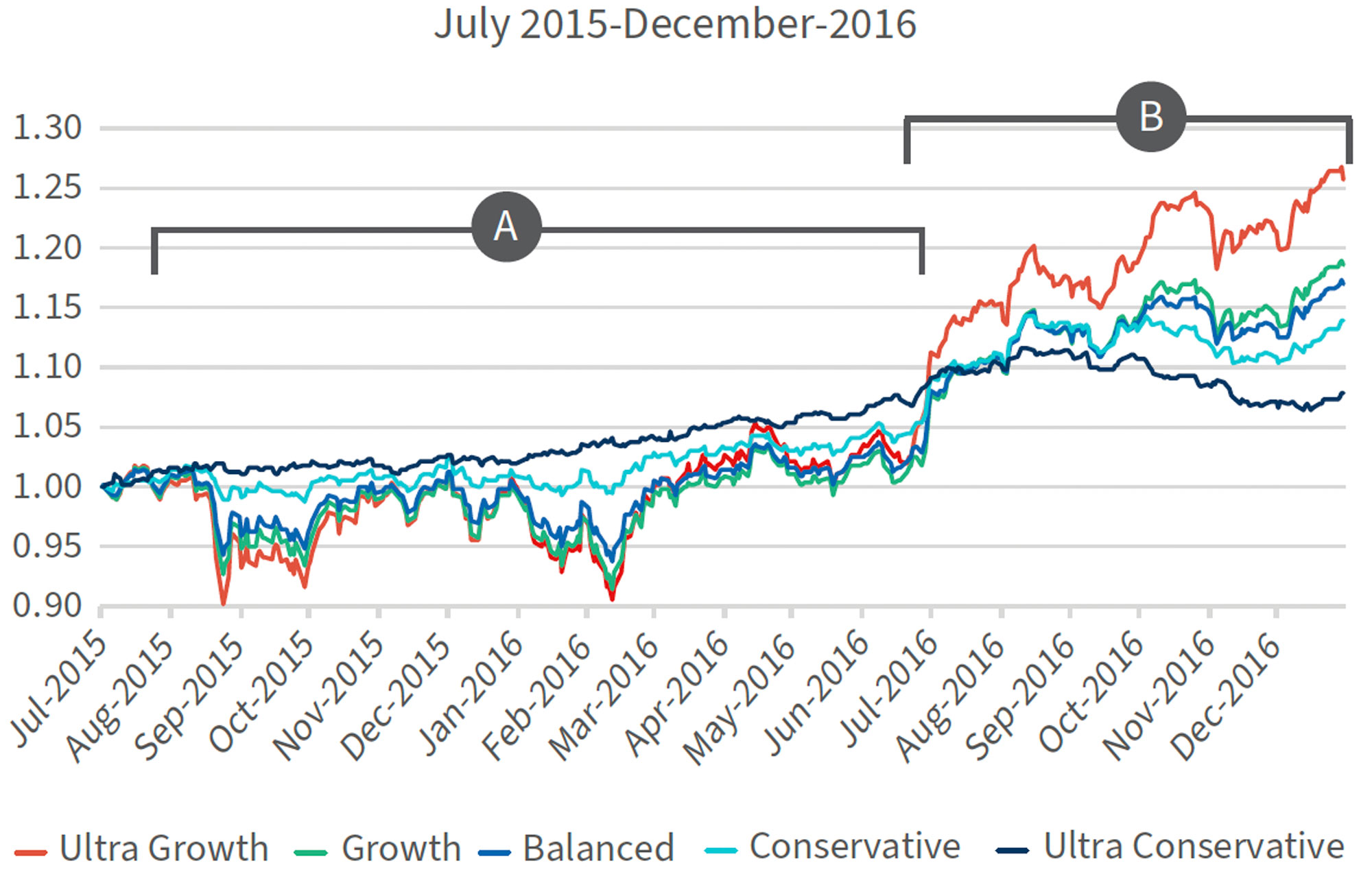

As illustrated in Figure 1, from 2008 onwards some studies suggest that low volatility (i.e. lower risk) portfolios have out-performed high volatility (i.e. higher risk) portfolios in the long run. The period analysed in Figure 1 shows that the low-volatility portfolio had an excess return of 121.4%, which is higher than the 62.5% excess return of the high-volatility portfolio.8 The outperformance is particularly apparent during significant crashes, such as the August 2015 global market sell-off or the March 2020 COVID-19 market crash.

Figure 1: Capital of high and low volatility portfolios

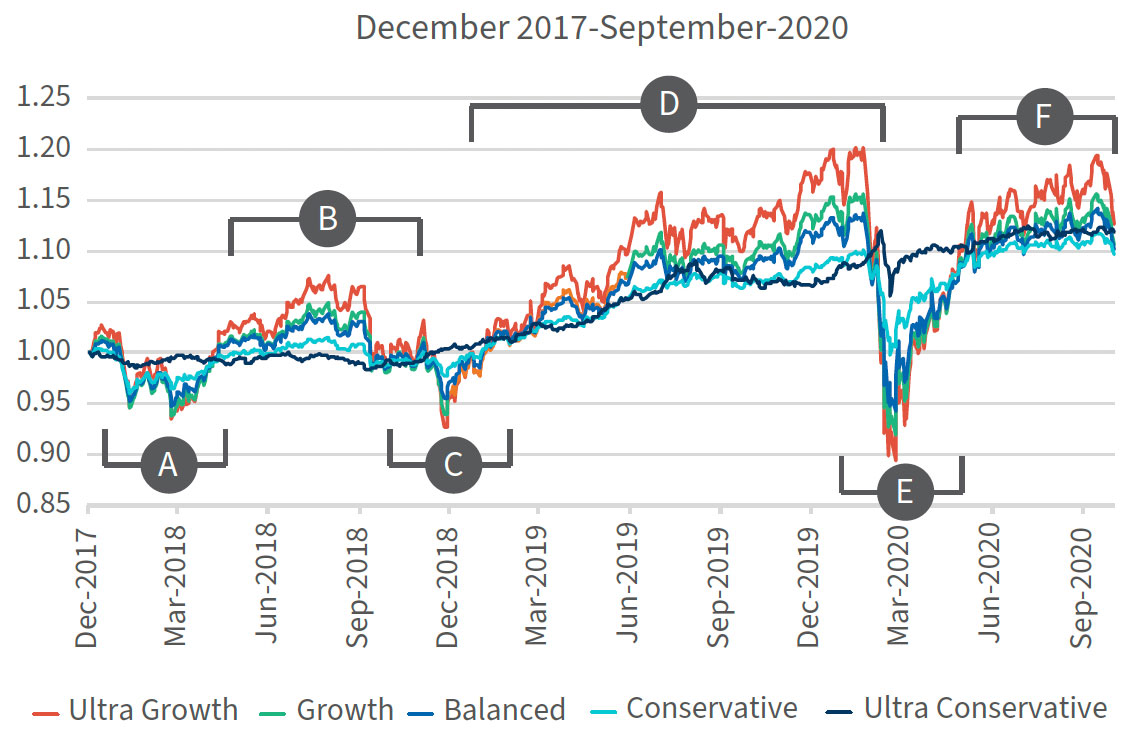

Looking at the performance of various risk categories of the FTSE UK Private Investor Series9 for different asset allocations, from higher risk to lower risk, also shows that low-risk asset allocations can at times outperform high-risk ones (see Figure 2).

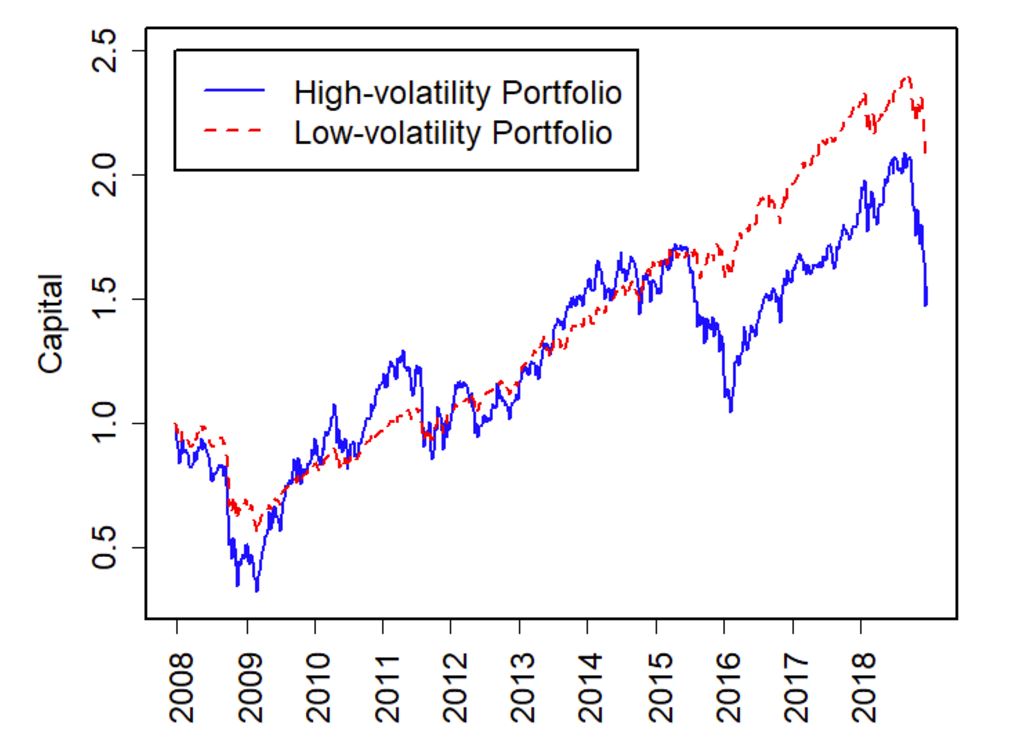

As seen in Figure 2, if an investor had invested shortly before the August 2015 global sell-off, then the highest-risk portfolio (in red) would have consistently underperformed the lowest-risk portfolio (in green) (see Figure 2, part A). In contrast, as seen in Figure 3, the higher-risk portfolio would have outperformed the lowest-risk portfolio over three periods (see Figure 3, parts B, D and F).

Figure 2: FTSE Private Investor Index, July 2015 – December 2016

Figure 3: FTSE Private Investor Index, December 2017 – September 2020

This emphasises the importance of the period analysed when comparing high- and low-risk investments, as well as emphasising that high-risk investments should not always be expected to outperform low-risk investments, and that the market timing of investments and divestments matters. Therefore, there is no certainty that the damages figure obtained from a counterfactual high-risk portfolio will systematically exceed the one obtained from a counterfactual lower-risk portfolio.

Active Versus Passive Investment

Investment portfolios are either passively or actively managed – active investors attempt to outperform the risk-adjusted returns of a specific benchmark by implementing various strategies, whereas passive investors seek to track a specific market index.

The choice between active and passive investment has been subject to many debates among economists.10 A study from Invesco analysing active fund managers over five different market cycles in 20 years showed:11

- Excess return: on an asset-weighted basis, 60% by value of high active share fund assets beat their benchmarks, after fees, across all market cycles studied (50% on an equal-weighted basis).

- Downside capture (which is a measure of how well an investment performs compared to a benchmark index during a down market): 64% by value of high active share fund assets had a better downside capture than their benchmarks across all market cycles (62% on an equal-weighted basis).

- Risk-adjusted returns: when historical returns were adjusted for risk, active funds outperformed passive benchmarks. 59% by value of high active share fund assets had a better measure of return per unit of risk than their benchmarks across all market cycles (53% on an equal-weighted basis).12

The economic environment and economic cycles may also be more favourable to a specific type of investment strategy. For example:

- Higher interest rates: will increase allocation trade-off between assets (such as bonds and stocks) and firms’ funding costs, accentuating uncertainty and dispersion between best and worst performing stocks. This will give more opportunities for active portfolio managers to implement their strategy and differentiate between the worst and best performers.

- Lower interest rates: will favour the stock markets in general, in which case passive portfolios or trackers might outperform active portfolio managers. This has occurred in the last decade with an unprecedentedly bullish US stock market. Active funds suffered outflows nearly every year from 2015 to 2020.

Proponents of active investing or passive investing each have plenty of evidence to cite, so active or passive investment is a consideration that investors cannot ignore when selecting an investment strategy.

When ensuring that the counterfactual portfolio is consistent with the counterfactual mandate, it would not be appropriate to use a passive investment counterfactual to benchmark an active portfolio mandate. As such, the question of active portfolio versus passive portfolio investment mandate is a central question for experts to consider when assessing damages.

High Level Principle for Sampling Suitable Counterfactual Portfolios

To identify a suitable counterfactual investment portfolio for calculating damages, it is important for experts to be provided with detailed information regarding the IRP and the nature and composition of the agreed investment mandate. Depending on the mandate for the counterfactual portfolio, and to eliminate the risk of hindsight when identifying a suitable counterfactual portfolio, one approach is to identify comparable investment managers that were available and open for investment in the relevant period.

Minimising sampling bias is essential to representativeness, objectivity and reliability. As with any sampling, outliers may need to be excluded from the database, but it is important to avoid introducing survivorship bias. So long as comparable funds complied with their investment mandate, their returns should be included. Therefore, funds that, for reasonable reasons (so excluding fraudulent funds for example), failed to survive the entire investment period considered for computing damages, should be retained in the sample.

Sampling existing fund managers to model damages is a robust and fair approach, as it does not diminish the market realities and uncertainties investment managers face when formulating investment decisions. Additionally, because it gives a range of outcomes, it is possible to draw a distribution and attribute a probability to such outcomes, helping the court with selecting the most probable outcome for awarding damages.

Final Thoughts

Calculating damages in investment management disputes is an exercise that requires significant knowledge of industry practices when constructing investment portfolios.

Estimating damages may be challenging, as the counterfactual investment portfolio may trigger investment decisions or rebalancing over time so that it remains compliant with the IRP and investment mandate – whether due to cash inflow and outflow, leverage, rebalancing or the distribution of counterfactual returns.

Estimating damages can also become computationally difficult owing to data limitations or if multiple scenarios are generated. In particular, when it comes to the investment period, disputes over the start and end dates may require the production of several damages scenarios to assist the court. Additionally, the frequency of actual versus counterfactual performance and availability of information may require frequent modelling over the investment period. The availability of historical information for some investments might not be disclosed to experts meaning they may need to enrich or reconstruct the data provided by using independent sources of information or making assumptions between different rebalancing dates.

Ultimately, the mechanics and assumptions relied upon for modelling damages can be subject to disagreements between experts, which in turn may drive differences in damages figures. The predominant driver of damages is usually the selected counterfactual investment portfolio. The more precise the information about an IRP and the agreed investment mandate, the more accurate the sampling and benchmarking of a suitable counterfactual investment portfolio can be.

The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and not necessarily the views of FTI Consulting, Inc., its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, or its other professionals. FTI Consulting, Inc., including its subsidiaries and affiliates, is a consulting firm and is not a certified public accounting firm or a law firm.

Footnotes:

1: CFA Institute Investment Risk ‘Profiling, a guide for financial advisors’, 2020.

2: Ibid.

3: Markowitz H. (1952) ‘Portfolio selection’.

4: Baird Private Wealth Management, ‘The Role of Alternative Investments in a Diversified Investment Portfolio’, 2013.

5: JPMorgan AM 2020, ‘Alternatives: from optional to essential’, exhibit 7 ‘Where Individual Investors put their money’.

6: FCA, ‘Understanding high-risk investments’, January 2021. https://www.fca.org.uk/investsmart/understanding-high-risk-investments

7: Baker M., Bradley B., Wurgler J. (2010), ‘Benchmarks as Limits to Arbitrage: Understanding the Low Volatility Anomaly’.

8: Jarrow R.A., Murataj R., Wells M.T. and Zhu L. (2021), ‘The Low-volatility Anomaly and the Adaptive Multi-Factor Model’.

9: “The FTSE Private Investor Index Series is a multi-asset index series providing market participants in the UK with a set of asset allocation benchmarks covering equities, fixed income, cash, property and other investments” - overview definition from LSEG.

10: Nobel Laureates Eugene Fama (the Efficient Market Hypothesis), William Sharpe (one of the originators of the CAPM and the creator of the risk-adjusted return measure called the Sharpe ratio) and Harry Markowitz have historically supported passive management.

11: John Maynard Keynes is a good example of how an investor can be active and invest in a way that differs from available indices. See Rathbones, ‘Active vs. passive investing — the great investment debate’ and Chambers & Dimson, ‘Retrospectives: John Maynard Keynes, Investment Innovator’.

12: Invesco (2017), ‘Think active can’t outperform? Think again’.

Date

5 décembre 2024

Téléchargez

Most Popular Insights

- Beyond Cost Metrics: Recognizing the True Value of Nuclear Energy

- Finally, Pundits Are Talking About Rising Consumer Loan Delinquencies

- A New Era of Medicaid Reform

- Turning Vision and Strategy Into Action: The Role of Operating Model Design

- The Hidden Risk for Data Centers That No One is Talking About