Finally, Pundits Are Talking About Rising Consumer Loan Delinquencies

Financial Markets Mostly Are Unconcerned

-

November 13, 2025

DownloadsDownload Article

-

The current sentiment across much of the economic punditry is that consumer spending is healthy enough and the average U.S. consumer is in decent shape financially despite some persistent economic challenges. Yes, consumer debt is at an all-time high, but so are home prices and equity markets, while unemployment remains low. Americans owe a lot but also own a lot and, overall, are faring relatively well, as asset price appreciation continues to outpace the growth of consumer debt.1 Consumer spending remains surprisingly resilient despite wide expectations it would weaken in the face of a sluggish sentiment, a slowing labor market, tariff impacts and still-nagging inflation.2,3,4,5 So, the main economic takeaway through mid-2025 is that household finances and spending are holding up well enough even with these headwinds.

But headline data that supports this conclusion does not adequately explain what is really going on, and how perilous it might be.

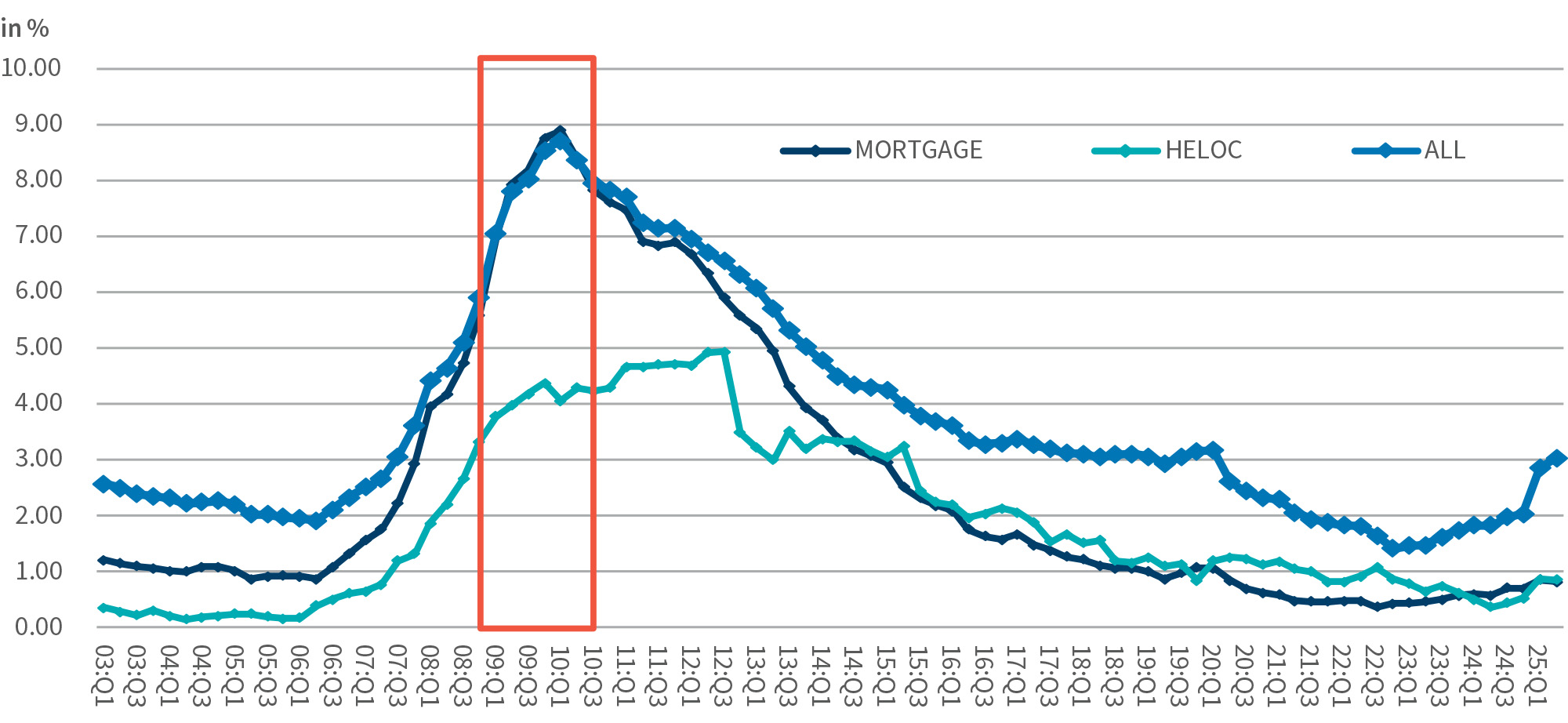

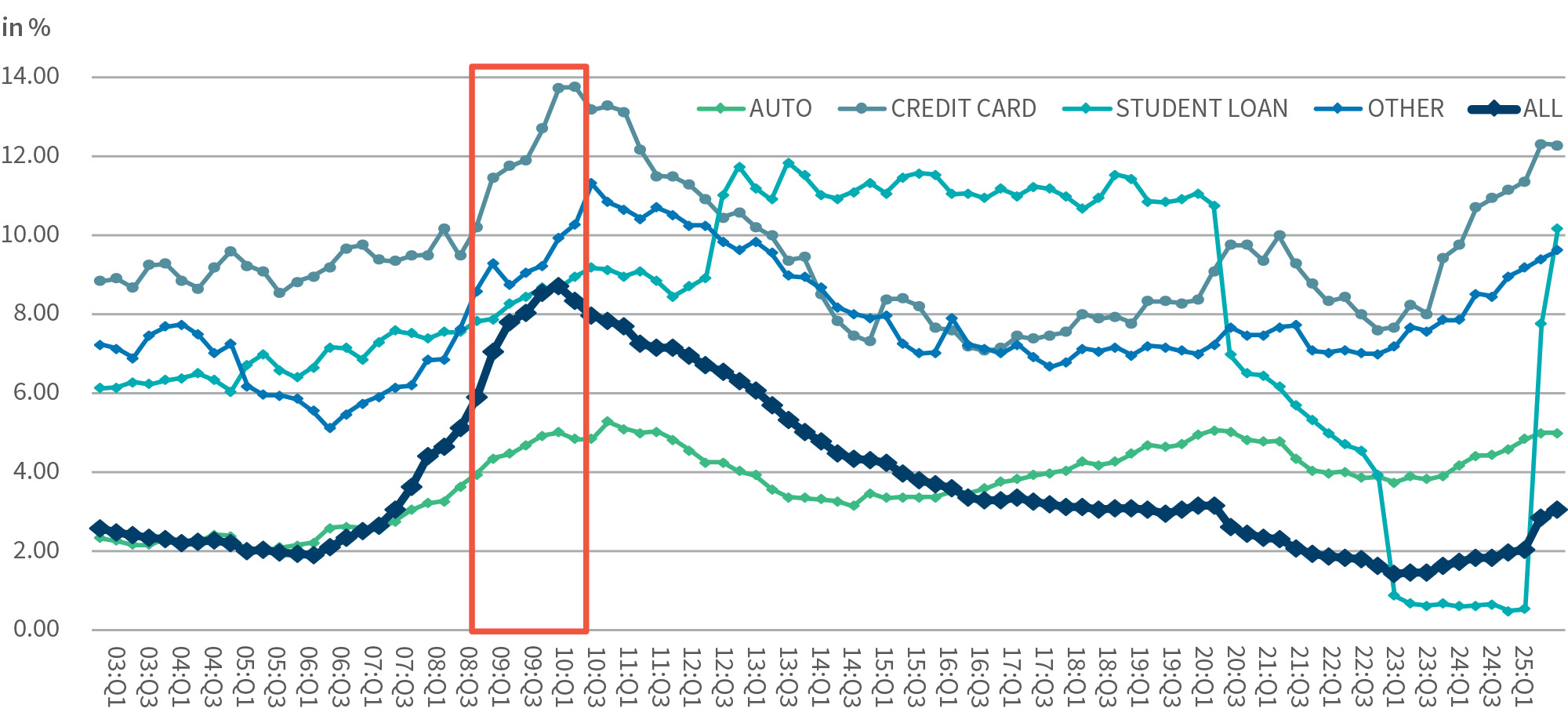

Some economists point out that relatively tame consumer loan delinquency and default rates are persuasive evidence that most households are staying financially resilient, but disaggregating outstanding consumer debt into its respective components by loan type paints a more troubling picture since 2023. It is true that the personal bankruptcy filings remain modest and are well below pre-pandemic levels, while the severe delinquency (90+ days) rate on total consumer debt remains moderate at around 3.0% compared to its long-term average of 3.8%. This improvement is overwhelmingly attributable to low delinquency rates on home mortgage debt, which is by far the largest component of consumer debt and historically has accounted for 67%-74% of total consumer debt. The severe delinquency rate on home mortgages is currently far below its long-term average, though it has ticked higher since 2023, but is hardly worrisome. Americans are staying current on their home mortgages, but many are falling behind badly on other debt they owe (Figures 1a and 1b), mainly credit cards, auto loans and student debt (collectively accounting for 25% of all consumer debt), which is indicative of mounting financial stress for households that are juggling their monthly debt payments.

There is an explanation for the divergence in severe delinquency rates among types of consumer debt in the post-pandemic period. Foremost, those who own homes with mortgages may be a distinctly different group of borrowers from a creditworthiness perspective than those who carry significant other consumer debt, so their respective delinquency rates don’t necessarily move in tandem, though they have tended to do so historically as there is considerable overlap between them. Homeowners today are determined to protect their home equity above all else, which may seem obvious but was not necessarily the case for many households during the housing bust of 2008-2011. Following the bursting of the housing bubble and the ensuing Great Recession, delinquency and default rates on home mortgages soared and stayed elevated for several years. Home mortgages that were deemed severely delinquent soared close to 9.0% of total mortgage debt from 2009-2010, an all-time high (Figure 1a).

But it wasn’t just insolvent homeowners who were defaulting on mortgages during this tumultuous period. It was also homeowners with little or no equity invested in their homes, thanks to ultra-low downpayment requirements on many home mortgages at that time, who saw little financial sense in continuing to make mortgage payments on homes that were very underwater (i.e., negative equity) with little prospect of a housing recovery. Many struggling homeowners opted to hand the keys back to lenders, especially in non-recourse states, rather than throw good money at homes with depressed market values in which they had little (if any) remaining financial stake. Many chose to move on from these homes and became renters. That dynamic has changed entirely over the last decade or so.

As home lending standards became more stringent after the housing bust, home buyers have ponied up considerably more money to make a down payment on a home purchase, typically 20%. Most homeowners now have lots of skin in the game, just as it used to be prior to the housing bubble; they also have unrealized gains, too, as residential home prices have continued to climb.

Homeowners today have lots more at stake financially compared to 2008-2011, while housing supply remains extremely tight and residential rental costs have soared since the pandemic. If you are fortunate enough to own a home, the monthly mortgage payment gets paid ASAP even if money is tight, because there practically is no feasible housing alternative. However, providers of other types of credit to cash strapped consumers are not faring nearly as well of late, as mortgage lenders take a larger share of consumers’ disposable income.

Consider auto loan payments, for instance, which also carry a high priority in the minds of cash strapped consumers. For most Americans, an automobile is more than a convenient mode of transport, it is essential to getting them to and from their jobs, especially in suburban and rural locales. Lose your car, and you might lose your ability to get to work as well (or take your children to school or to childcare). Moreover, auto lenders are famously known to repossess vehicles quickly before loan payment delinquencies can pile up, unlike home mortgage foreclosures that can take many months and considerable cost to enforce. Consequently, Americans have always made their auto loans a high priority payment if there was not enough monthly cash to go around. Given the importance of staying current on auto loans to the functional lives of so many Americans, deteriorating payment performance for auto loans can be considered the canary in a coal mine for non-prime borrowers. By contrast, credit card debt and student loan debt fall lower on consumers’ payment priority scale, as payment remedies often can be dragged out for many months with fewer immediate or severe consequences.

Not only have severe delinquency rates (excluding home mortgages) escalated sharply since 2023, but some are now approaching levels reached during the depths of the Great Recession (Figure 1b). Severe delinquency rates on outstanding auto loans and credit card debt have increased by 34% and 60%, respectively, since the end of 2022. It is startling to realize that severe delinquency rates on non-mortgage debt are nearly as high today amid a period of relative economic prosperity as they were during the worst recession of our lifetimes. So, it is hardly surprising that 36% of YouGov respondents recently said their family finances are in worse shape today than a year ago (45% said the same, 14% said better, 5% Don’t Know)— far higher than negative response rates of the pre-pandemic period in 2018-2019 — even as the domestic economy chugs along and financial markets soar.6

Delinquent auto loans have gotten the attention of the business media in recent weeks following the Chapter 7 bankruptcy filing of Tricolor Holdings, an auto dealer and finance company targeting car buyers with subprime credit, and the dismal quarterly results of used auto retailer CarMax.7 These events speak to weakening new business in the auto sector and the deteriorating performance of auto loans, with severe delinquencies recently reaching 5.0% of outstanding balances (Figure 1b), above its long-term average of 3.8% and slightly surpassing the worst levels of 2008–2010. These loan delinquencies are mostly concentrated in the subprime category (<620 credit score) of borrowers but are also accelerating notably in the next two lowest credit score categories. Similarly, the rate of credit card debt considered severely delinquent is near the worst levels of 2009–2010 at more than 12% of outstanding balances.

Figure 1a - Percentage of Loans 90+ Days Delinquent

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Figure 1b - Percentage of Loans 90+ Days Delinquent

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Severely delinquent student loans have soared in near-vertical line fashion over the past year once the multi-year pause on federal student loan payments during the pandemic period ended in September 2024. Apparently an extended four-year reprieve on these payments did little to help borrowers catch up with their loan delinquencies to any notable degree. Various measures to provide some student loan debt relief or forgiveness by the Biden administration, many of them done through executive orders, are being rescinded by the Trump administration.

The general discussion topic of how Americans’ earning and spending habits are holding up is inherently misleading because economic metrics for the “average U.S. consumer” are a figment based on aggregated economic data which is not representative of any particular group. Rather, it is an amalgam of a relatively small contingent who are doing exceedingly well, a larger cohort who are hanging on, and the largest group who are taking on more water even as they bail. There is nothing new about this pattern but it has become more pronounced in the post-pandemic period, as we pointed out last month in our discussion of the “vibe-session,” with well-off consumers increasingly driving spending and income growth (here we’re not referring to “the 1%” but the top 15%-20% of Americans based on income) while the spending of other income groups further lags their representative size to varying degrees.8 Moreover, spending by lower income cohorts increasingly has been debt financed. There is anecdotal evidence of this divide all around, whether it is the myriad articles on the bleak outlook of Gen Zers or this election season’s political ads that focused on issues of affordability and inflation. Consider that a central issue in the race for NJ governor was the mundane topic of rising utility prices. All of this is occurring amid a broad economic backdrop that is showing respectable growth, moderating inflation and continued asset price appreciation.

Some have little quarrel with this phenomenon of “two economies” provided the top-line keeps growing, while others question the sustainability of such lopsided growth and see the increasing reliance on higher income earners to propel total spending as potentially destabilizing to the economy and divisive for the country. This is potentially a fraught discussion topic that veers into the political realm. But one thing is almost certain; if so many Americans are struggling financially during a period of relative prosperity, then the next true recession we have, whenever it happens, is going to be brutal for a large percentage of households.

If these vulnerable consumers are your customers, you should consider yourself warned.

Footnotes:

1. “Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2024,” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (28 May 2025).

2. Escobar, Sabrina, “Retail Sales Rise Again in August Bucking Economic Slowdown,” Barron’s (16 Sept. 2025).

3. Dyson, Jim, “Retail Sales Exceed Forecasts Despite Sinking Consumer Sentiments,” CFO Dive (16 Sept. 2025).

4. Bartash, Jeffry, “Retail Sales Are Strong for the Third Month in a Row,” MarketWatch (16 Sept. 2025).

5. Slok, Torsten, “We in the Economics Profession Need to Look Ourselves in the Mirror,” Apollo Academy (1 Oct. 2025).

6. “Changes in the Personal Finances of American Families,” YouGov.com (29 Sept. 2025).

7. Tucker, Sean, “A Big Auto Lender Went Bankrupt. Here’s What It Means,” Kelley Blue Book (12 Sept. 2025).

8. Eisenband, Michael C., “There is a Corporate Vibecession Too,” FTI Consulting (9 Oct. 2025).

Related Insights

Related Information

Published

November 13, 2025

Key Contacts

Key Contacts

Global Chairman of Corporate Finance

Downloads

Most Popular Insights

- Beyond Cost Metrics: Recognizing the True Value of Nuclear Energy

- Finally, Pundits Are Talking About Rising Consumer Loan Delinquencies

- A New Era of Medicaid Reform

- Turning Vision and Strategy Into Action: The Role of Operating Model Design

- The Hidden Risk for Data Centers That No One is Talking About