Fiscal Fuel Theft and the Mexican Overview

-

October 21, 2025

-

Abstract

Fuel theft in Mexico, known as huachicol, has been a common practice for criminal groups, resulting in significant losses of government revenue and escalating violence. Traditional fuel theft consists of physically stealing gasoline from pipelines. However, the practice has evolved into a more sophisticated version: fiscal fuel theft or huachicol fiscal. This version of huachicol exploits customs and tax loopholes that allow shell companies and false invoices to move fuel across the country while avoiding payment of the import tax known as the IEPS (Impuesto Especial sobre Producción y Servicios).1 Fiscal fuel theft creates compliance risks for companies and financial institutions that may unknowingly interact with corrupt networks. In this context, it has become crucial to apply enhanced due diligence and stronger compliance measures to mitigate exposure.

Fiscal Fuel Theft

Fuel theft refers to the appropriation of crude oil or refined petroleum products, a criminal practice known as huachicol in Mexico.2 The first documented cases of huachicol in Mexico emerged during the 1980s and became more professionalized throughout the 1990s, reaching their peak under the presidential administrations of Felipe Calderón (2006-2012) and Enrique Peña Nieto (2012-2018).3 After President Enrique Peña Nieto opened the energy sector to foreign investment, fuel theft intensified; fuel prices escalated, and criminal organizations took the opportunity to grow the black market, offering gasoline at lower prices than the formal sector.4

Fighting Fraud:

Top 2025 Insights

Read Now

As the huachicol practices became more complex, Pemex’s revenue losses deepened, hitting the state oil company hard.5 In 2018, the president Andrés Manuel López Obrador (“AMLO”) announced a joint action plan to protect Pemex’s infrastructure against fuel theft. It relied on deploying more than 4,000 soldiers and marines across 15 distribution systems.6 As a result, pipeline tapping declined, and organized crime groups shifted toward smuggling and misclassification schemes at ports, known as fiscal fuel theft. According to the U.S. Department of the Treasury, both traditional and fiscal huachicol have become some of the most lucrative criminal businesses, along with drug trafficking.7

According to Insight Crime, a think tank and media organization, these operations have caused enormous fiscal losses and violence in the country; the issue has become more complex with the fraudulent participation of government officials who allow the fuel theft network to continue operating.8 In recent months, the Mexican Attorney General’s Office, known as Fiscalía General de la República (“FGR”), has seized several shipments of illegal fuel; additionally, the FGR has conducted a series of arrests of high-ranking officials, like Vice Admiral Farías Laguna and other Navy personnel exposed.9 Fiscal fuel theft has been under the radar for the last decade; however, the most recent scandal involving high-ranking officials from various government levels and institutions, organized crime groups, and businessmen has highlighted the need for more robust compliance strategies for private companies to mitigate abstract risks.10

Fiscal Fuel Theft: Inherent Risks

InSightCrime also notes that fiscal fuel theft goes beyond tax evasion; it undermines governance, security, supply chain, energy investors, and society at large.11 Fuel has always been in high demand and widely distributed, and as a result, the illegal activities surrounding fuel create four main categories of risks.12

- Fiscal and Economic Risk

Fuel-related crime has been estimated to cost billions of dollars annually in lost revenue and to generate enormous profits for illegal fuel networks. This issue also causes unfair competition as illicit networks supply cheaper fuel by avoiding taxes and distorting pricing and market conditions.13 Pemex has reportedly lost 3.8 billion dollars to fuel theft in the past five years.14 Many service stations across the country have resorted to buying stolen fuel, according to Enrique Félix Robelo, president of Onexpo (Organización Nacional de Expendedores de Petróleo).15 - Governance and Institutional Risks

Fiscal fuel theft exposes sophisticated fraud schemes such as false import declarations or irregular documentation. According to OPIS (Oil Price Information Service), illicit fuel providers evade taxes by falsely labeling oil products.16 For these schemes to succeed, they require active collusion by authorities, eroding institutional credibility and the rule of law. The recent involvement of high-ranking Navy officers shows how organized crime can infiltrate trusted institutions.17 This is particularly sensitive given that, according to INEGI (the National Institute of Statistics and Geography) surveys, the Mexican Navy consistently ranks among the country’s most trusted institutions.18 - Organized Crime, Violence, and Territorial Control

Further, fiscal fuel theft is managed by criminal groups that rely on bribery, threats, and violence. These networks have proven to be highly adaptive, allowing them to sustain and expand their operations. The illicit revenue finances weapons, corruption, and territorial control.19 - Corporate and Financial Compliance Risks

Companies risk unwittingly transacting with criminal networks and violating anti-money laundering (“AML”) regulations. Organized crime uses shell companies to evade taxes, and launder proceeds, making it harder to detect illicit counterparties.20 In Mexico, these shell companies have become a centerpiece to disguise illegal shipments, as well as falsify tariff codes and documents that allow the untaxed fuel to enter legally. These risks demonstrate the complexity of fiscal fuel theft and the systemic nature of the problem; it deteriorates institutions through corruption, fortifies organized crime groups, and companies face exposure to regulatory and reputational harm. Fiscal fuel theft cannot be understood as an isolated act of tax evasion but as a whole system.

The Mexican Overview

Pemex, the state-owned oil company, leads the national energy sector in Mexico and manages the infrastructure through which most fuel circulates. Therefore, it has traditionally borne the brunt of losses from fuel theft. However, the pattern of losses has shifted, as Pemex’s losses decreased with the decline of physical pipeline tapping and the evolution of fiscal fuel theft through tax evasion schemes.21 As a result, the exposure has reduced for Pemex but increased for the federal government.22 Avoiding the payment of IEPS on imported fuel shifts the damages to the government’s tax revenue, hence massive losses in public finances and the capacity to fund services, infrastructure, and social programs. Essentially, fiscal fuel theft attacks the fiscal foundation of the state by evading tax collection.23

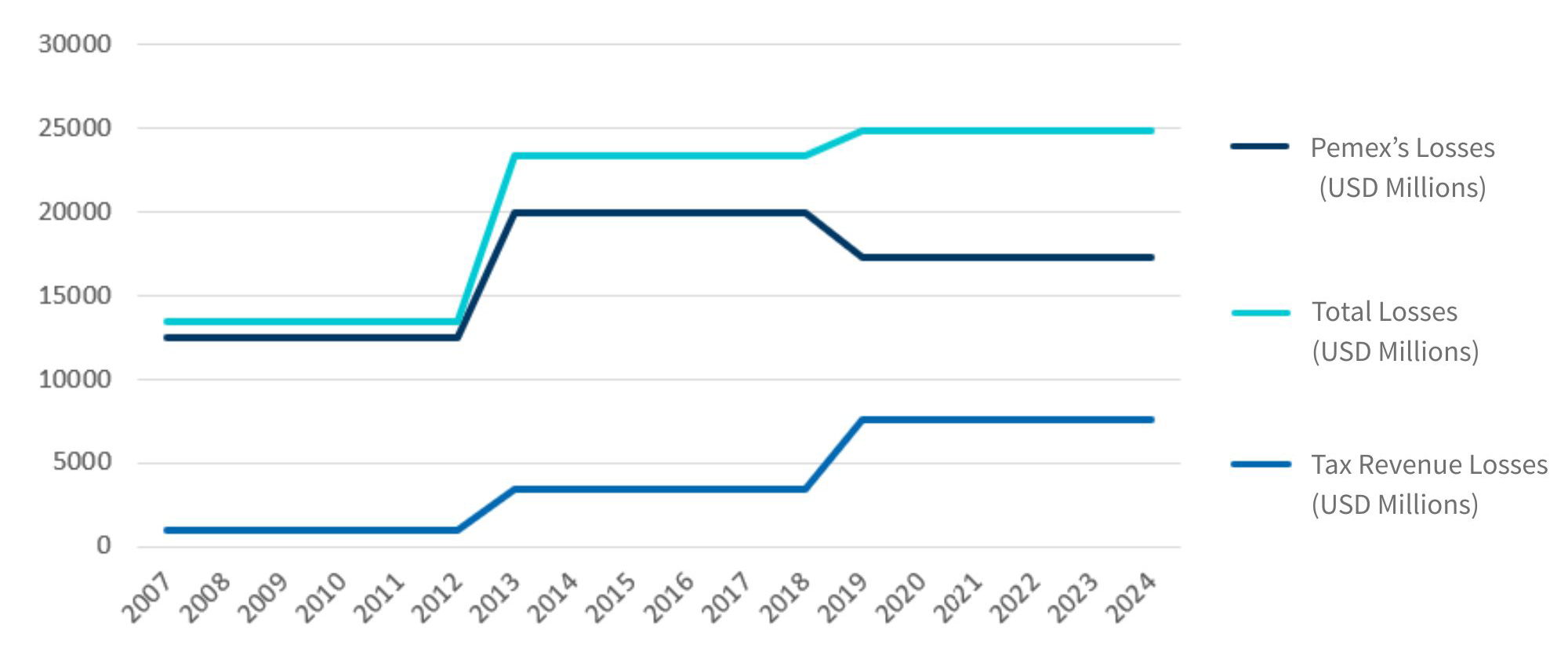

The following graphic demonstrates the change in revenue losses throughout the presidential terms of Calderón, Peña Nieto, and López Obrador.

Estimated Economic Loss(es) From Traditonal and Fiscal Fuel Theft in Mexico, 2007–2024

Data adapted from Francisco Barnés de Castro, Energía A Debate (2025).

As shown in the graphic, fiscal fuel theft increased after Peña Nieto opened the oil sector to foreign investment, as higher import volumes and the liberalization of fuel prices were accompanied by regulatory and enforcement gaps that were used to evade tax obligations.24 This shift from traditional fuel theft to fiscal mechanisms allowed the creation of sophisticated smuggling strategies.

Organized crime groups have found a way to transport contraband effectively by blending illicit fuel with legitimate fuel shipments and reducing the plausibility of being detected.25 Often, organized crime groups use shell companies that serve to create false invoices, paperwork, ownership, and shipments that look legal. Because these companies have no real operational footprint, the theft is less visible and has lower risk than the traditional huachicol.26 For example, according to the US Department of the Treasury, the Sinaloa Cartel and the Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación (“CJNG”) are the most notorious groups to rely on bribing and violence to smuggle fuel through the black market.27

The fiscal fuel theft crisis has been the central debate in the last couple of weeks in Mexico when several navy and customs officials were arrested after a fuel seizure in Altamira, Tamaulipas. This event unmasked a fuel trafficking network that allegedly relied on regulatory loopholes and corrupt officials to avoid paying IEPS.28 The IEPS tax is applied to gasoline, diesel, and other fuels; it’s used as a fiscal tool to regulate prices. When avoiding the IEPS, the prices are lower compared to legitimate importers or Pemex, resulting in the loss of money in guaranteed tax income for the government. The misclassification of goods is a common practice for fiscal fuel theft, where fuel is labeled as other types of chemical goods that are not taxed. Another mechanism for fiscal fuel theft is the manipulation of the invoicing process to avoid taxes, meaning that documents that record the transaction between buyer and seller are modified. With the help of shell companies registered as the legal entity for shipments entering Mexico, it is difficult to identify the ultimate beneficiaries. For instance, the seizure of the vessel Challenge Procyon revealed how the Customs Central Laboratory (Laboratorio Central de Aduanas, operated by the National Customs Agency of Mexico) labeled more than 30 cargoes as “lubricant oil additive” instead of gasoline to avoid the IEPS. The misclassification allowed the cargo to enter under false documentation to evade taxes.29

According to the news outlet, El País, the fiscal fuel theft network has been operating since 2024 with the help of high-ranking officials of the Navy and businessmen. In the aftermath of the scandal, the death of Navy and Marine personnel was reported; the official causes of death have been unclear, which has led to speculation.30

The current panorama is showing its complexity by involving organized crime, the government, the private sector, and even Mexican society. Fiscal fuel theft also relies on corporate and administrative mechanisms; regulatory loopholes enable illicit transactions by creating structural channels through which criminal networks can institutionalize revenue theft. These loopholes create hidden vulnerabilities for companies where they may unknowingly operate with shell companies or other intermediaries involved in tax evasion. Such exposures could result in compliance failures, financial penalties, and reputational harm.

How Can We Help

The rise of fiscal fuel theft underscores a broader risk for companies operating in Mexico: doing business without thoroughly understanding counterparties can expose organizations to money laundering networks, corruption schemes, and organized crime. Companies must strengthen third-party due diligence, supply chain vetting, and compliance frameworks to reduce exposure.

FTI Consulting Mexico supports clients by performing reputational due diligence and integrity assessments to identify red flags, verify counterparties, and to help provide the assurance needed to engage in business relationships without jeopardizing operations, reputation, or regulatory compliance.

Additional Author: Sofia Perezalonso, Junior Consultant

Footnotes:

1: The IEPS (Special Tax on Production and Services) is a federal excise-type tax that applies to the production, sale, and import of certain goods and services—most notably gasolines and diesel, tobacco products, alcoholic and flavored beverages—as defined in the IEPS Law. It is a material source of federal tax revenue, though collections can vary due to fuel-related stimuli and price policies. Cámara de Diputados. (2021). Ley del Impuesto Especial sobre Producción y Servicios (IEPS). Diario Oficial de la Federación. Link.

2: Vivoda, Vladeo, Ghaleb Krame and Martin Spraggon, “Oil Theft, Energy Security and Energy Transition in Mexico,” MDPI Resources, 12 (2), Article 30 (February 17, 2023).

3: Lemus, J. Jesús, “Huachicol: Calderón lo forjó; Peña lo institucionalizó, y AMLO se lo quedó,” La Opinión de México (October 6, 2025).

4: Alire García, David and Marianna Parraga “Explainer – Mexico’s fuel woes rooted in chronic theft, troubled refineries,” Reuters (January 11, 2019).

5: Peralta, Ricardo, “Historia del huachicol en México,” El Heraldo de México [Opinion Column] (July 2, 2025).

6: “Plan Conjunto de Atención a las Instalaciones Estratégicas de PEMEX,” Foro Jurídico (December 27, 2018).

7: U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Targets Major Mexican Cartel Involved in Fentanyl Trafficking and Fuel Theft,” [Press release] (May 1, 2025).

8: Woolston, Sam, “How Fuel Theft Drives Mexico’s Violence Epidemic,” InSight Crime (September 26, 2025).

9: Corona, Sonia, “Detenidos el vicealmirante Manuel Roberto Farías Laguna y una decena de funcionarios por tráfico de combustible en México,” El País (September 6, 2025).

10: “Huachicol fiscal: el eslabón invisible que distorsiona el mercado,” Industry Energy Magazine (September 26, 2025).

11: InSight Crime, supra n. Viii.

12: Baruc, Mayen, “Huachicoleo en México: 5 puntos clave del negocio ilícito que provoca pérdidas millonarias al país,” Milenio (May 17, 2025).

13: Soud, David, Ian Ralby and Rohini Ralby, “Downstream Oil Theft: Countermeasures and Good Practices,” Atlantic Council Global Energy Center (May 2020).

14: AP News, “Mexican authorities seize nearly 4 million gallons of stolen fuel,” [World News] (July 7, 2025).

15: “El 30 por ciento de la gasolina del país es de procedencia ilícita: Onexpo,” [Reprint of article by Gilberto Lastra Guerrero in Milenio] Onexpo Nacional (September 29, 2025).

16: Rodríguez, Daniel and Karla Omaña, “Mexico 101: Illegal Fuel Imports and Blends,” OPIS (April 4, 2023).

17: Andrade, Julián, “Corrupción en la Marina: El lado oscuro del control aduanero,” Forbes México (September 16, 2025).

18: “Percepción sobre el desempeño de las autoridades de seguridad pública y justicia,” Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI)(2025).

19: Mosqueda, Sara, “Seeking Revenue, Cartels Turn on the Fuel Tap,” ASIS International Security Management (June 12, 2023).

20: “Obradorismo bajo escrutinio: investigan vínculos de red de huachicol con familia de Audomaro Martínez, señala Peniley Ramírez,” Aristegui Noticias (September 15, 2025).

21: Woolston, Sam, “The Story of Mexico’s Multibillion-Dollar Fuel Theft Crisis,” InSight Crime (September 8, 2025).

22: Mares, Marco A., “Huachicol fiscal, 600 mil millones de pesos,” El Economista (October 7, 2025).

23: “Huachicol fiscal: como opera y por qué afecta a todos los mexicanos,” Verifigas (August 26, 2025).

24: Barnés de Castro, Francisco, “El huachicol: Una estimación de su impacto económico,” Energía A Debate (July 10, 2025).

25: Zea, Tibisay, “The hidden black market fueling Mexico’s cars – and its cartels,” The World (July 29, 2025).

26: “The Cartel’s Hidden Fortune: How Shell Companies and Crude Oil Became the New Drug Trade,” Parriva (June 2, 2025).

27: Ferri, Pablo, “La DEA apunta ahora a las redes del CJNG tras el golpe hace dos semanas al Cártel de Sinaloa,” El País (September 29, 2025).

28: Guerra, Claudia, “Las dos versiones del huachicol: del robo en ductos al fraude en aduanas,” El País (September 11, 2025).

29: Barajas, Abel, “Registraban laboratorios de Marina aceite, pero era gasolina,” Reforma (September 22, 2025).

30: Carabaña, C. “La red de tráfico de combustible de los hermanos Farías Laguna operó al menos desde 2023: 69 envíos y más de 150 millones de dólares en beneficios,” El País (September 17, 2025).

Related Insights

- Corporate Impact of FinCEN’s Recent Orders and FTO Designations in Mexico Read Article

- The New “Operation Casablanca”? Challenges and Opportunities in the Designation of Mexican Cartels as FTOs Read Article

- Know Your Risk: Terrorist Designation of Cartels on Business Interests in Mexico Read Article

Published

October 21, 2025

Key Contacts

Key Contacts

Senior Managing Director

Director

Senior Consultant

Most Popular Insights

- Beyond Cost Metrics: Recognizing the True Value of Nuclear Energy

- Finally, Pundits Are Talking About Rising Consumer Loan Delinquencies

- A New Era of Medicaid Reform

- Turning Vision and Strategy Into Action: The Role of Operating Model Design

- The Hidden Risk for Data Centers That No One is Talking About