Not to be Overlooked: Taxation and Currency in Damages Awards

-

2024年12月05日

下载Download Article

-

Reproduced with permission from Law Business Research Ltd. A previous version of this article was published in June 2024 and can be found here: https://globalarbitrationreview.com/guide/the-guide-damages-in-international-arbitration/6th-edition/article/taxation-and-currency-issues-in-damages-awards.

Summary

In the dispute resolution process, a significant amount of time can be spent on small points, but there are two areas that are often overlooked or given insufficient attention despite their significant impact – the effect of tax and currency on the quantification of losses. What issues can arise? How can valuers address these in a proportionate way? What pitfalls can be avoided?

- Awards may be enforced in a different jurisdiction or be subject to different tax treatment than the lost profits or wasted costs incurred. There is a risk that if not assessed carefully, assumptions as to taxes may lead to an award that is too high or too low.

- At the extremes, a claimant may claim for losses assessed on a post-tax basis, and then be taxed on that award, leading to significant under-compensation. Conversely, they could claim on a pre-tax basis and then not be taxed on the award, leading to significant over-compensation.

- A detailed assessment of taxes on lost profits and awards is generally disproportionate in cost and time, but thoughtful high-level consideration of the issues that is supported by appropriate documentary evidence, moves the resulting award closer to meeting the objective of restoring the financial position of the claimant.

- Parties often operate in multiple currencies and may have converted lost cash flows into another currency if they had been achieved. Due to exchange rate fluctuations, assumptions as to whether and when such conversions would have taken place can have an important effect on the value of losses awarded.

- As with taxes, careful consideration of currency issues is necessary to meet the objective of an award of damages as closely as possible.

Dangers of Distortion

Taxes are a fact of corporate life and the treatment of tax in the calculation of awards of compensation can have a significant effect on the value of an award to a recipient. As the world and business become more global, currency can also be a significant factor in damage awards. Over-compensation and under-compensation are possible if taxes and currency are not considered appropriately or at all.

What taxes should apply? What currency is applicable? Is it a question of law, or a question of economic loss? These issues can often be complex, particularly given the timing and international context of many claims but can have a substantial impact and should not be brushed over lightly.

Calculating Damages: The Principle of Full Compensation

The calculation of an award of monetary damages in bilateral investment treaty (‘BIT’) arbitrations is based on the principle that “reparation must, as far as possible, wipe out all the consequences of the illegal act and re-establish the situation which would, in all probability, have existed if that act had not been committed.”1 A substantially similar principle generally applies in international commercial arbitration, that the claimant should be restored to the position it would have enjoyed ‘but-for’ the breaches found by the tribunal – the ‘principle of full compensation’.

The principle of full compensation provides that any award should restore the claimant to the same position that it would have enjoyed ‘but-for’ its injuries, taking account of all relevant factors, including applicable taxation and relevant currency movements. This is considered both in the financial position the claimant would have been in but-for the breach or breaches, and the financial position it actually finds itself in.

Why Does Tax Matter?

Taxation of corporate profits is well established in most jurisdictions. These taxes would often have applied to any additional profits a claimant would have made but-for its injuries, and also often apply to any award received by a claimant.

The treatment of taxation by tribunals in setting awards can make an important difference to the net proceeds of an award to a claimant and whether the principle of full compensation has been met. Put simply, if an award itself is subject to tax and the value of the award has been calculated by reference to profits lost on a post-tax basis, under-compensation of a claimant is likely to arise. In these circumstances, the principle of full compensation would make it necessary for the claim to include a gross-up for tax payable on the award.

Although taxes themselves are very common, the question of tax is often largely and sometimes entirely disregarded by the parties to a dispute – but why is that?

- Damage calculations are often already complex, time-consuming and expensive for the parties to prepare, even before consideration of tax issues.

- Tax is itself a complex area, often requiring evidence from additional experts if it is to be examined in detail.

- The amount of taxes that would have been or will be paid in certain situations can depend on performance in the future or the hypothetical position of both the legal entity and its corporate group providing for an even broader scope for analysis and estimation than that required for other aspects of loss assessment.

- To assess the extent of taxes that a claimant will pay on any award, it is often necessary to make estimations concerning the future actual performance of the claimant – a loss-making company may pay no taxes on an award, whereas the same company, if profitable, would pay taxes.

All in all, the impact of tax on damage awards is complex, varies greatly and can involve a lot of hypotheticals and estimates.

Issues Raised by Tax Analysis

To illustrate the issues at hand, consider a relatively straightforward case in which a claimant is only seeking compensation for trading losses suffered in its home jurisdiction. To analyse fully the tax treatment of the hypothetical lost profits, the following would need to be taken into account:

- Over which periods would the lost profits have arisen?

- What is the applicable corporation tax rate in each period?

- What is the basis of the calculation of taxable profits in each period?

- Are other losses available for offset either within the period, from earlier periods, or surrendered from affiliates?

A similar analysis in relation to the award claimed in compensation for the lost profits, would need to take the following into account:

- On what basis will the award be subject to tax? Does it follow the taxation of the lost profits or is it treated as a separate source of income or gains subject to different rules?

- In which period would it be subject to tax? At the time of the claim or at any future award payment?

Further considerations come into play when the injury causes loss to an asset. Depending on the applicable jurisdiction, damage to an asset may result in a deemed disposal or part disposal of the asset for tax purposes, and any compensation for such a loss may be treated as proceeds of such a disposal. This may apply when the asset is tangible property, or intangible property such as a brand, which may be a recognised asset on the claimant’s balance sheet. The capital gain or loss will be calculated according to applicable tax principles, deducting allowable costs from the proceeds of disposal. This calculation may not be consistent with the method used to calculate the award, which may be by reference to loss of revenue, and this would need to be considered to ensure appropriate post-tax compensation.

Further refinement would be needed in cases in which a claimant seeks compensation for profits that would have been generated partly or entirely in jurisdictions other than its home jurisdiction. This is very often the case in BIT cases, and also for those commercial cases in which a parent company is claiming for losses suffered by its foreign subsidiaries.

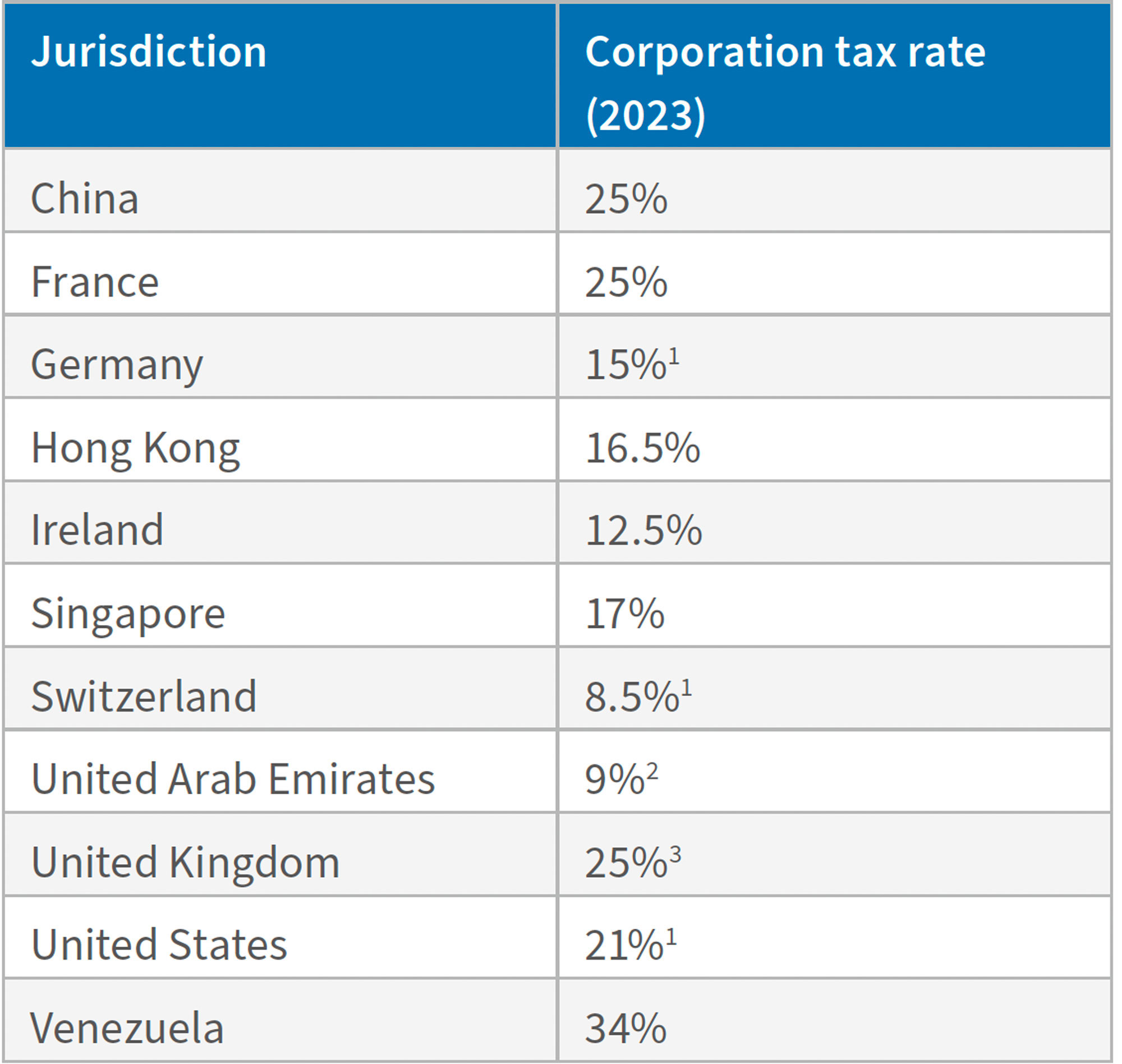

Although international law may apply to the arbitration process, tax law is not international. Each jurisdiction has sovereign power to determine the taxation of companies resident or active in that jurisdiction. The headline tax rate per jurisdiction can vary substantially, from as little as 9% to as high as 34%. In addition to the applicable rate, the method of identification of the amount of profits to multiply by the tax rate also varies by jurisdiction – whether that is taking account of reliefs, exemptions, losses and affiliated company tax positions. Furthermore, the sovereign power may conflict with approaches imposed by supranational bodies. For example, the European Court of Justice (‘ECJ’) ruled that methods approved by Ireland for Apple to use were unlawful aid and so held that Ireland must collect tax of €13 billion.

Many tax jurisdictions are in the process of implementing the OECD’s Pillar Two Model Rules. This is a new framework for multinational groups and has been designed to address the digitalisation of the economy. Taxpayers in scope of the rules calculate their effective tax rate where they operate, and pay a top-up tax to achieve a 15% minimum tax rate and generally paid in the jurisdiction of the ultimate parent. Whilst Pillar Two is relatively new, additional complexity in the computation of damages should not be ignored.

Headline corporation tax rates in selected jurisdictions (2023)

Notes: (1) These rates do not include applicable taxes levied in the jurisdiction at a municipal, cantonal or state level; (2) The UAE introduced a corporation tax regime of 9% from June 2023. Prior to this date no corporate taxation existed; (3) The UK headline corporation tax rate increased from 19% to 25% from April 2023.

In cross-border cases, it is necessary to consider whether there is symmetry of taxation between the lost profits, which are hypothetically subject to tax in the home jurisdiction of the injured company, and the award, which is potentially taxable as income or capital gains when received by the injured company or an affiliate in another jurisdiction.

This situation also raises the question, in relation to commercial cases, of equity between jurisdictions, as well as between claimant and defendant. When tax is lost in one jurisdiction as a result of an injury inflicted on one company and then paid in another jurisdiction as a result of compensation paid to a parent or affiliate in that other jurisdiction, some form of settlement might be expected between tax authorities in different jurisdictions. However, there is no mechanism in the established tax treaty system for tax incidentally received in one jurisdiction to be reimbursed to another, so this type of process is not yet formally possible, in commercial cases at least.

There is also the possibility of a claimant receiving an award calculated on a pre-tax basis, which is then not subject to tax, where circumstances change or an alternative tax return position is taken. Such over-recovery would also be a violation of the principle of full compensation.

Perspectives From the United Kingdom, United States and France

The issues involved are complex and a detailed analysis of tax issues can risk creating a separate arbitration within the arbitration, requiring further evidence of fact, evidence from tax experts and potentially introducing excessive technical detail, creative assumptions and uncertainty of tax outcomes outside the control of the tribunal.

What are the perspectives from the United Kingdom, the United States and France? What approaches have been taken to tackle this financially complex area? What principles drive these decisions?

UK Perspective

The case of British Transport Commission v Gourley2 confirmed a general principle of compensation consistent with the principle of full compensation. However, the degree of approximation with which this principle is applied to the treatment of taxation on damages is variable.

The UK corporation tax treatment of an award of compensation is determined by the nature of the loss to which the award refers. When corporate trading activity has been damaged, and the award is calculated by reference to the loss of trading profits, it will be treated as taxable trading income. The timing of taxation of an award is likely to follow the period in which the award is recognised in the recipient’s accounting income.

When compensation is claimed for damages other than loss of trade profits, it is necessary to determine whether the claim is in respect of a capital or revenue loss, and for capital losses, whether the loss relates to an underlying asset treated as chargeable for corporation tax purposes. A significant body of case law addresses the capital or revenue distinction, and UK statute defines chargeable assets. The area is complex and the facts will determine the UK tax treatment.

When compensation is claimed for permanent damage or deprivation of use of a fixed capital asset, it is possible that an award will be treated as a capital receipt. The tax treatment of the award will then be determined by whether the damage can be related to underlying property that is a chargeable asset for the purposes of calculating corporation tax on disposal. In such cases, an award may be considered a deemed disposal or part-disposal of the asset, and a capital gain or loss would then arise for corporation tax purposes. It was established in the case of Zim Properties that the right to take court action in pursuit of compensation or damages is of itself an asset for capital gains tax purposes.3 This case related to damages for professional negligence, and under current UK practice, a punitive tax cost can arise.

Intangible assets, such as goodwill, were also historically treated as chargeable assets for corporation tax purposes; however, specific rules now apply to intangibles acquired from third parties or created after April 2002, such that gains or losses on disposal will be treated as revenue income or loss.

A capital receipt not related to an underlying chargeable asset will not be subject to corporation tax under general principles. However, the basis on which receipts are characterised as non-taxable capital is dependent on the underlying facts, subject to a wide range of case law precedent and, therefore, not clearly defined.

A UK-based claimant would, therefore, need to identify the nature of the lost profits, whether capital or revenue, to analyse the tax treatment of the amount claimed. To restore the ex ante position, the calculation of the amount of the award should take account of the tax treatment of both the loss and the award itself.

US and French Perspectives

US courts have approached the issue of taxation of arbitration awards in the context of employment tribunal cases adopting a ‘make whole’ purpose that is broadly consistent with the principle of full compensation.4 These anti-discrimination cases are not directly relevant to the discussion relating to international commercial and investment treaty awards, but some insightful guidance emerges, such as the tribunal’s emphasis on the significance of the particular facts of each case and placing the burden of proof on the claimant to establish any adverse tax consequences to be taken into account.

Turning to investment treaty cases involving US-based claimants, the award in the case of Chevron and Texaco v Ecuador included lengthy analysis of the tax consequences in Ecuador of profits lost.5 After the Republic of Ecuador agreed that no further tax, penalties or interest would be payable on the award, the award was calculated net of tax.

In Corn Products v Mexico, the net-of-tax award was made to a US parent rather than to the Mexican subsidiary, to ensure no additional taxes were payable in Mexico.6 It is not clear whether US taxes would ultimately have been payable by the claimants in these cases or whether this was relevant in the calculation of the award. If the award was subject to tax in the United States, the ex ante position may not have been restored unless the profits lost in Mexico would also ultimately have been subject to US tax.

A final point of fairness arises in the context of investment treaty awards in the case of the expropriation of a company by a government. As a first approximation, the value taken by the expropriating government is the after-tax value of the relevant entity. If an award against a government based on the pre-tax value of the entity is paid to the parent company on the grounds that the award will be taxed in the parent company’s jurisdiction, then the losing government will pay an award greater than the value taken. The excess between the value taken and the amount paid would then effectively be a tax windfall for the government of the parent company’s jurisdiction.

It is perhaps to guard against such an outcome that the French General Tax Code stipulates that the French state will levy no taxes on awards paid in relation to expropriation or similar measures by a foreign government.7

Calculating The Tax Impact in Practice

One approach often used by a claimant is to quantify its claim before deducting any corporation taxes the affected entity would have paid, on the grounds that any award will itself be taxed, leaving the claimant’s net position in line with the principle of full compensation. This approach is appropriate if the taxation of the lost profits would have been broadly in line with taxation of the award, both by reference to the method of calculation and marginal tax rate for the periods in question.

An alternative approach that is also often used is for a claimant to state its claim after deducting the taxes the entity would have paid, and to leave it to the tribunal to award the amount that would constitute full compensation post-tax. This approach essentially defers the question of taxation to the hearing or post-hearing stage. Such an approach would be appropriate if it is clear that the award itself would not be subject to tax. However, when the tax treatment of the award is not addressed at all, the claimant would be at risk of under-compensation.

Given the complexities involved in assessing taxes, even at a relatively simplified level, it is likely to be useful to secure the input of individuals with hands-on experience of tax assessment in the relevant jurisdictions, to validate the approach being taken. This input may come from the parties’ own finance teams, existing external taxation advisers or consulting firms active in the assessment of losses in international arbitration. Ultimately, ‘it is better to be roughly right than precisely wrong’ and so even a slight look into the issue of taxation is likely a move in the direction of the ‘right’ award.

Arbitration Awards and Currency

Why Does Currency Matter?

Issues of currency arise very frequently in assessing losses in international arbitration. The critical issue is not so much the currency in which any award is to be paid – unless the currency is truly unusual or subject to exchange controls,8 a payment in one currency can today be quickly and very cheaply exchanged into another currency if the recipient wishes. Instead, the critical issue is in what currency is the award to be calculated, and on what dates are any amounts in other currencies to be translated into the award currency?

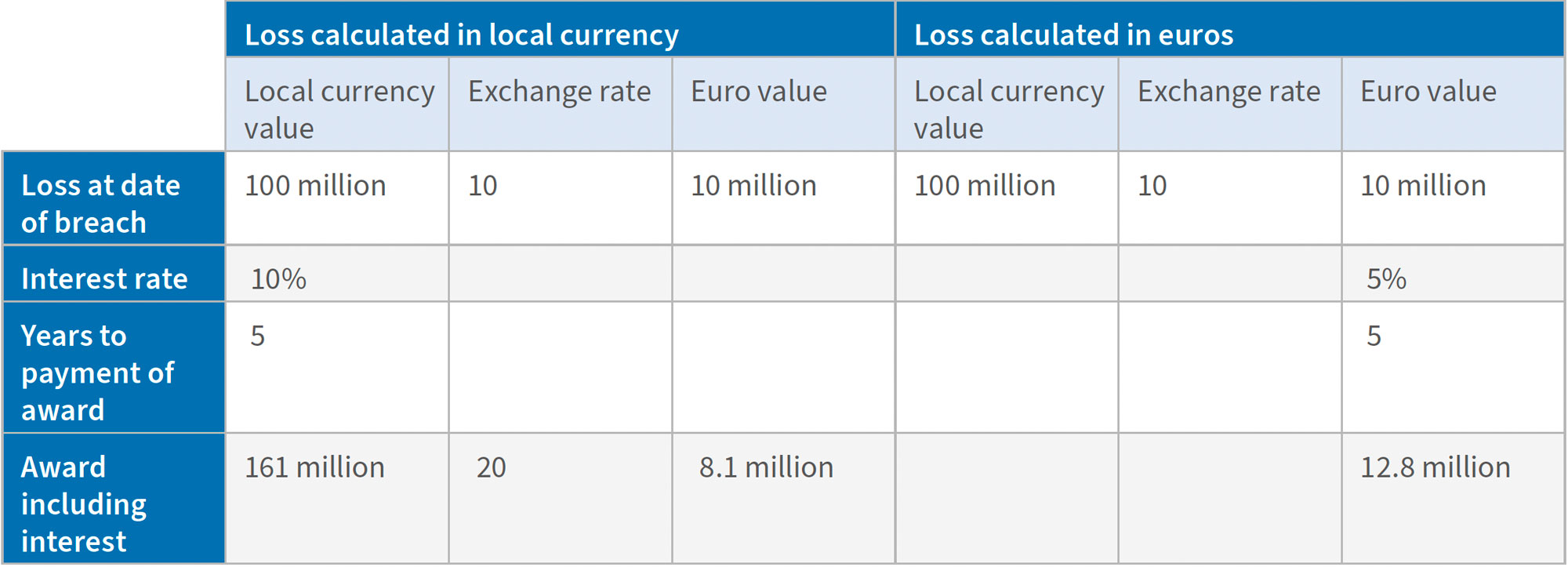

Consider a loss suffered most immediately in a local currency, of 100 million currency units, and an award five years later. During the intervening period, local currency interest rates have been at 10%, euro interest rates at 5%, and the exchange rate has depreciated from 10 to 20 local currency units to the euro, all as shown in the table below.

Assume further that it is uncontentious between the parties that the award is to be paid in euros.

Straightforwardly, the euro value of the loss at the date of breach was €10 million. The respondent argues that the award is to be paid at the euro equivalent of the loss after it has been assessed in local currency and brought forward at the applicable rate of interest. Using this approach, the value of the award when paid is €8.1 million – lower than the €10 million value of the loss at the date of breach, because the effect of the weakening of the local currency exchange rate more than offsets the relatively high interest rate.

The claimant argues that the correct approach is to translate the loss into euros at the date of breach, using the then-prevailing exchange rate, and then to add interest to the present. This gives rise to an award of €12.8 million, more than 50% higher than the figure proposed by the respondent. If the local currency had appreciated, the reverse would apply and the claimant would be better off under the former approach.

The approach to currency selected by the tribunal, therefore, will have a significant effect on the amount recovered by the claimant. The effects of this general point can sometimes be far more dramatic; one case that was ultimately decided by the UK’s House of Lords involved an award of the local currency equivalent at the date of payment of $20,000 that would have been nearly $3 million if translated into dollars at the date of breach.9

Legal Approaches to Currency and Damages

The evolution of English law relating to currency and damages further illustrates the importance of this issue. For much of the 20th century, English law held that damages awarded in the English courts must be awarded in pounds sterling.10 Damages claimed in contract law were to be converted into pounds at the date of the alleged breach, disregarding subsequent fluctuations in relevant exchange rates.

Although this treatment may be appropriate for a claimant predominantly doing business in pounds, it exposes claimants operating primarily in other currencies to fluctuations in the value of the pound. This benefits the claimant at the expense of the defendant when the value of the pound appreciated during the relevant period by more than the differential between the applicable interest rate in each currency, and vice versa. During the Bretton Woods era of pegged exchange rates, currency fluctuations, and the risks thereby imposed on parties to disputes, were very limited, apart from occasional devaluations. However, with the emergence of floating exchange rates from 1968, the associated risks grew.

The practice changed in two steps. The first step arose in 1974 when the Court of Appeal confirmed an award by commercial arbitrators expressed in a foreign currency, which had for some time been the practice among commercial arbitrators in appropriate circumstances.11 Then, in 1975, the House of Lords, citing the development of floating exchange rates, explicitly rejected the principle that claims for damages must be expressed in sterling.12From that point forward, claims for breach of contract under English law could be expressed in foreign currency. If any conversion was needed for enforcement purposes, it would take place at the date the court authorised the claimant to enforce the judgment – the date of payment.13This decision reduced the scope for foreign exchange rate movements to affect parties to a dispute inappropriately.

This then leaves the question, often hotly disputed in international arbitration today, of the currency in which to express an award. The English law approach starts with an examination of the relevant contract. However, the mere fact that payments under the contract are to be made in a particular currency does not necessarily imply that that is the appropriate currency for the award of damages.14 The correct treatment is that damages should be calculated:

Under this principle the loss suffered by a French charterer under a contract denominated in dollars, for delivery to Brazil of goods that were damaged as a result of a breach by the shipowner, was subject to an award in French francs, because the charterer had to use French francs to buy the Brazilian cruzeiros with which to compensate the cargo receiver.16

International courts and tribunals have consistently expressed compensation in freely convertible currencies. In Biloune v Ghana, the claimants were compensated in relation to investments made in pounds sterling, Deutschmarks, US dollars and Ghanaian cedis – with the latter not being freely convertible. The tribunal awarded compensation in the first three currencies but awarded the fourth amount in US dollars.17

In selecting the appropriate convertible currency or currencies for an award, international law reached similar conclusions to English law at an earlier point in time, but, perhaps unsurprisingly, they are not as systematically applied. The tribunal in the Lighthouses arbitration between France and Greece stated in 1956:

Other institutions, including the United Nations Compensation Commission and the Iran-US Claims Tribunal, have adopted a similar approach.

Several mechanisms have been used by international tribunals to implement this principle in cases in which the foreign exchange value of one of the possible currencies of the award had depreciated by more than any differential in the applicable interest rate. First, the loss can be converted into the currency of the investor at the date of the breach. This is the approach taken by the tribunal in Sempra Energy v Argentina, after the Argentine peso fell against the dollar to less than a third of its value at the date of the breach. Second, and rather more unusually, the loss could be assessed in some third currency that has not depreciated. The 1956 Lighthouses arbitration between France and Greece, which related to events in the 1920s, since which the French franc had depreciated by 90% and the Greek drachma by even more, illustrates this. This tribunal accepted the claimant’s request to use the US dollar, which had been relatively stable in value during this period, as the money of account. Third, and even more unusually, some special adjustment could be made by the tribunal. In SPP v Egypt, the tribunal adjusted the amount awarded in US dollars for the relatively high general dollar price inflation that had applied between the 1978 breach and the 1982 award, using the change in the US Consumer Price Index. Finally, compensation may still be made in the depreciating currency if the associated award of interest is sufficient to offset the effect of foreign exchange depreciation.19

Valuer’s Approach to Treatment of Currency in Damages Awards

Without specific instruction, the valuation expert will assess currency issues by reference to the principle of full compensation, by assessing the financial position of the claimant but-for the breach, and comparing that to the financial position of the claimant in actuality. The effects of taxation on an award calculated in one currency by reference to a loss suffered in another, and associated currency differences, may also need to be considered to achieve full compensation.

To implement this principle, a valuation expert must form a view as to the likely use by the claimant of the cash flows lost due to the breach. This involves grappling, from a valuation point of view, with the same issues as those addressed under English law when an arbitrator or judge considers ‘which currency most truly expresses the claimant’s loss’.

A valuation expert may be able to bring financial evidence relevant to this question of which currency most truly expresses the claimant’s loss. Examination of a claimant’s financial statements or other accounting information may allow a valuer to test assertions made by the claimant relating, for example, to the currency mix of a claimant’s revenues, costs, assets and liabilities, to a company’s foreign exchange hedging strategy and other relevant elements.

If a loss relates to a lost stream of cash flows – as in the case of most lost profits assessments, some expropriations, and many cases in which losses are assessed as of a present date rather than as a value of a business or asset at a past date – then the timing of those lost cash flows may be doubly important. This is because the later in time a loss in a particular currency is felt, the less the value of that loss in that currency at the date of assessment. However, if for award calculation purposes each lost cash flow is translated into the second currency at the date it would have been incurred, then the date of each lost cash flow will determine the exchange rate that is applicable. The interaction of the timing of the lost cash flows with movements in the relevant exchange rate may have a major effect on the overall value of the claim.

Finally, international law examples focus on methods to insulate claimants against situations in which depreciation in the currency of the respondent state would reduce the value of an award to the inappropriate detriment of the claimant. However, it can arise that the respondent state’s currency appreciates rather than depreciates after the date of the breach. From a valuation expert perspective, the principle of full compensation would insulate claimants from any associated benefit – as in the case of currency depreciation, the loss would be translated into the award currency at the date it was felt. To do otherwise would be to give claimants a one-way bet on currency movements subsequent to the date of breach – a one-way bet with a potentially significant financial value that could, in principle, be quantified using option-pricing techniques.

Case Study

Tax

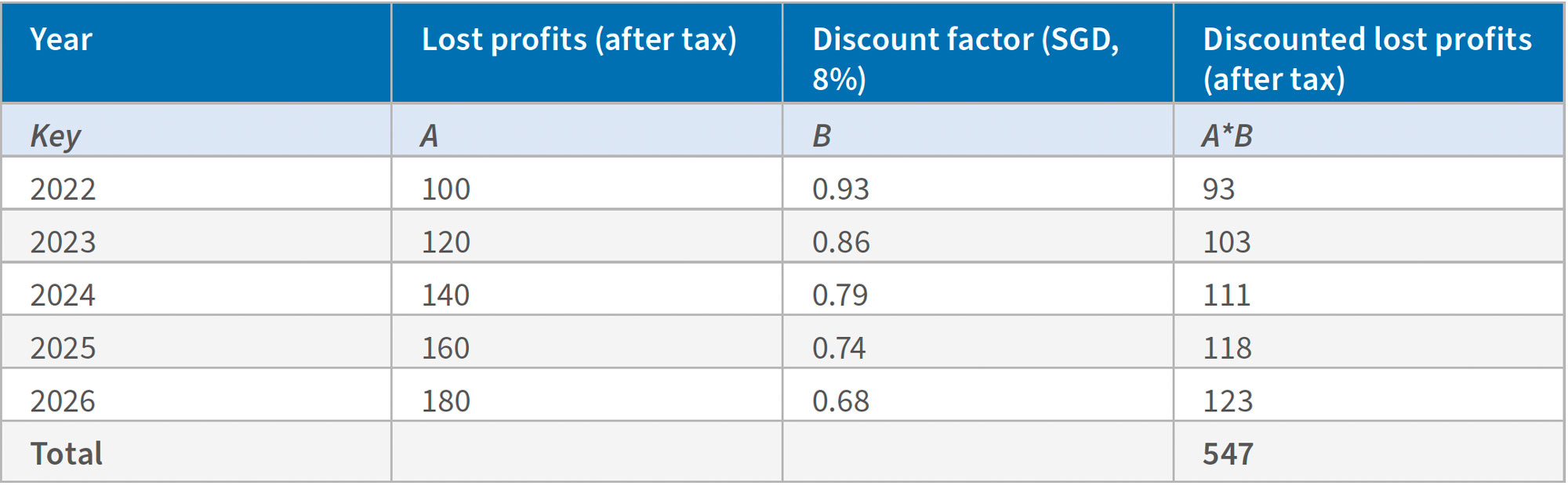

In a breach of contract case, the claimant’s lost profits were estimated by calculating the profits the claimant would have earned absent the respondent’s breach. The operating currency of the affected entity was USD and the claimant’s other activities are all denominated in SGD, and we initially assume the lost profits would, but-for the breaches, have translated each year from USD into SGD. The lost profits are then quantified by discounting them to a date of assessment (1 January 2022 in this case) using the claimant’s Singapore dollar weighted average cost of capital (‘WACC’) which we assume to be 8%.

Claimant’s losses (SGD million)

On these assumptions, the claimant’s losses as at the date of assessment amount to SGD 547 million, as shown above. If the award is subject to tax in Singapore, then it would be necessary to apply a tax gross-up to the amount awarded to ensure that, after tax is paid, the claimant is fully compensated. For example, if the award would be subject to tax at the Singapore corporate tax rate of 17%, then the claimant would receive an after-tax amount of (1 – 17%) which equals 83% of the gross amount awarded. The grossed-up award is then calculated by dividing the target after-tax amount by 83%, so the amount to be awarded would be SGD 547 million/ 83% = SGD 659 million. Similarly, if the award would be taxed in a jurisdiction with a tax rate of 25%, the grossed-up amount would be SGD 547 million/ (1 – 25%) which equals USD 729 million.

Currency

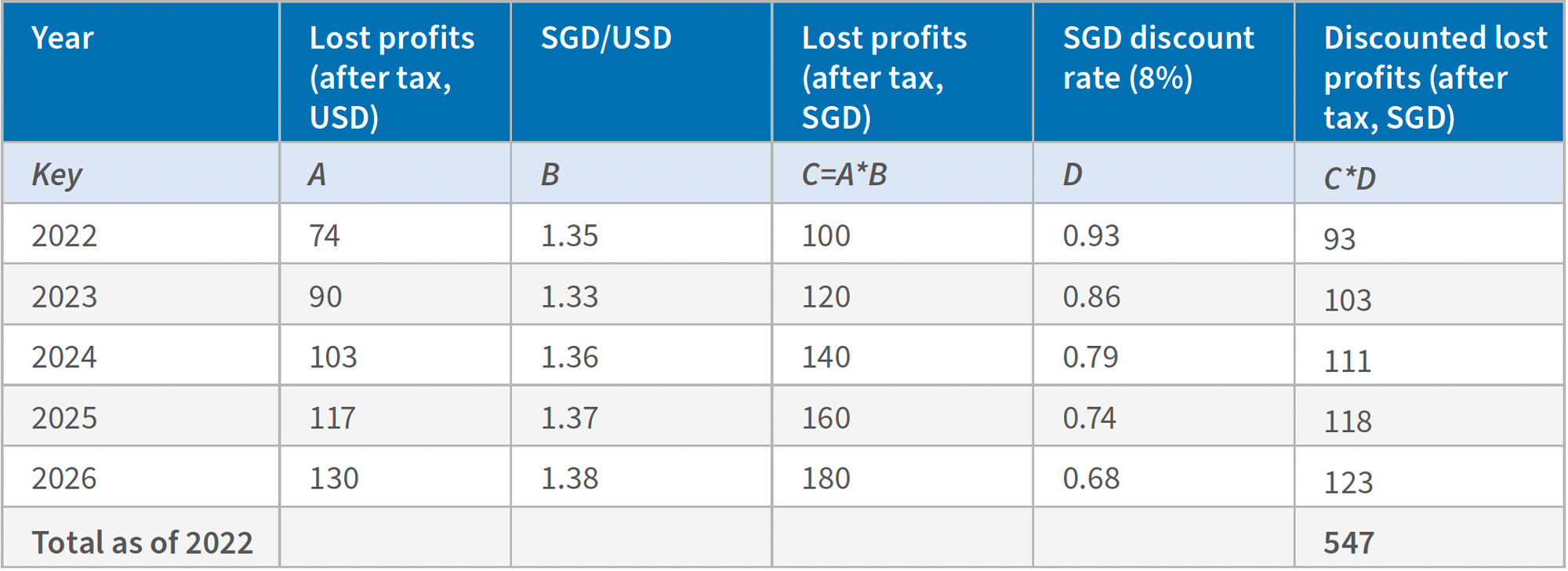

The above lost cash flows are consistent with an assumption that the losses in US dollars would have been converted into the claimant’s currency, the Singapore dollar, at each year’s exchange rate and then discounted to the date of assessment at a discount rate denominated in SGD. This is shown in the table below, which expands on the ‘claimant’s losses’ table above.

Claimant’s losses – translated to SGD year by year (million)

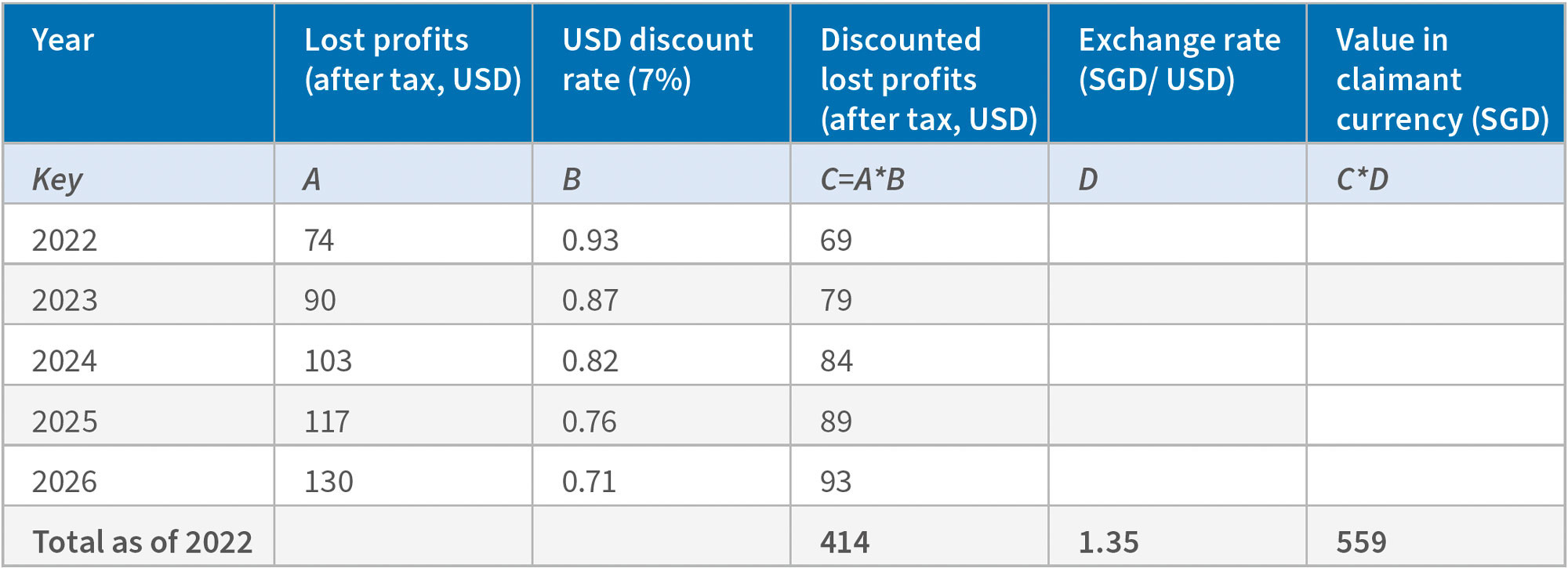

Alternatively, the claimant might argue that the lost cash flows would have been kept in US dollars through the period of loss – perhaps reinvested in this or another venture of the claimant’s group. In such a situation, the lost profits would be calculated as a lump sum in 2022 money of USD 414 million by applying a US dollar denominated discount rate which we assume to be 7%, and then exchanged into the claimant’s currency of Singapore dollars at the January 2022 exchange rate of SGD 1.35 per US dollar, to give a loss of USD 559 million.

Claimant’s losses – assessed in USD and translated to SGD at date of assessment (million)

Which of these two approaches to currency is more appropriate is a question of fact and expert evidence as to the more realistic assumption regarding the use to which the claimant would have put the lost cash flows if it had received them. In the above example, the claim amount is higher in the second situation in which losses are assessed as a lump sum in USD as of 2022 and then translated into SGD, however in general either approach could lead to a higher claim, depending on the facts surrounding the case in question.

Final Thoughts

The complexities of quantifying the impact of taxes in determining awards that meet the compensatory principle can mean parties devote little time to the issue. However, focusing more on the correct tax treatment will benefit the parties and also move the award in question closer to fulfilling the compensatory principle.

Issues of the currency in which losses are suffered and awarded as damages can also make a significant difference to amounts awarded. Parties sometimes attempt to argue for the treatment that most favours their position, even if that does not tie in to the circumstances of the case. Moreover, careful attention is needed to address issues of currency, exchange rates and their interactions with interest and discount rates, to ensure claims are appropriately stated and awarded.

The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and not necessarily the views of FTI Consulting, Inc., its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, or its other professionals. FTI Consulting, Inc., including its subsidiaries and affiliates, is a consulting firm and is not a certified public accounting firm or a law firm.

Footnotes:

1: Established by the Permanent Court of International Justice (predecessor to the International Court of Justice) in the Chorzów Factory case of 1928.

2: HL 1955.

3: Zim Properties Ltd vProctor, 58 TC 371.

4: Eshelman v Agere Systems Inc. 2005 WL 2671381.

5: Chevron Corporation (USA) and Texaco Petroleum Company (USA) v Republic of Ecuador (March 2010), PCA Case No. 2009-23, cited in Nhu-Hoang Tran Thang, ‘Tax Gross-Up Claims in Investment Treaty Arbitration’, February 2011.

6: Corn Products International Inc v United Mexican States (March 2010), ICSID Case ARB(AF)/04/1, cited in Nhu-Hoang Tran Thang, ‘Tax Gross-Up Claims in Investment Treaty Arbitration’, February 2011.

7: Article 238 bis C.

8: Ripinsky and Williams, in their 2008 book ‘Damages in International Investment Law’, cite the tribunal in the Vivendi v Argentina ICSID case, and the Iran-US Claims Tribunal, both of which state that it is the ‘frequent’ or ‘usual’ practice of tribunals to provide for payment of damages in a convertible currency (chapter 10).

9: Attorney General of the Republic of Ghana vTexaco Overseas Tankships, The Texaco Melbourne, cited in ‘McGregor on Damages’ (18th edition, McGregor, Sweet & Maxwell, 2009), 16-045.

10: ‘McGregor on Damages’, Chapter 16, at 16-019.

11: Jugoslavenska Oceanska Polvidba v Castle Investment Co Ltd, 1974.

12: Miliangos v George Frank Textiles, 1975.

13: ‘McGregor on Damages’, at 16-028.

14: Ibid, at 16-038.

15: Commenting on Services Europe Atlantique Sud (SEAS) vStockholms Rederiaktiebolag SVEA, often known as The Folias, as quoted in ‘McGregor on Damages’, at 16-039.

16: The Folias, per McGregor on Damages, at 16-037.

17: Award on Damages and Costs of 30 June 1990, as quoted in 'Ripinsky and Williams, ‘Damages in International Law’, BIICL 2008, page 395.

18: Ibid.

19: See Ripinsky and Williams, section 10.1.2 for further discussion of these points.

发布于

2024年12月05日

主要联络人

主要联络人

Senior Managing Director, Head of Asia Economic & Financial Consulting

资深董事总经理

资深董事总经理

Most Popular Insights

- Beyond Cost Metrics: Recognizing the True Value of Nuclear Energy

- Finally, Pundits Are Talking About Rising Consumer Loan Delinquencies

- A New Era of Medicaid Reform

- Turning Vision and Strategy Into Action: The Role of Operating Model Design

- The Hidden Risk for Data Centers That No One is Talking About