Cloudy Crystal Balls Don’t Deter the Soothsayers

-

January 10, 2022

DownloadsDownload Article

-

Every year around this time, usually late December into January, the media loves to feature stories or segments with predictions for the upcoming year that inform audience expectations, with prominent pundits offering forecasts in their respective fields of expertise, be it the economy, markets or politics.

The predictions of experts assumedly are more credible than those of casual observers, or so the thinking went until COVID-19, which has humbled much of the punditry and dispelled the belief that experts can foretell events or trends much beyond a few months out. This year especially, it seems that many expert predictions were prefaced either by self-effacing comments or some qualifying language that acknowledged the difficulty of forecasting accurately in this strange environment. Instead, we now tend to view these forecasts more as educated guesses, albeit informed ones, in a world that has become increasingly complex, interconnected, full of second- and third-order effects, and generally less predictable.

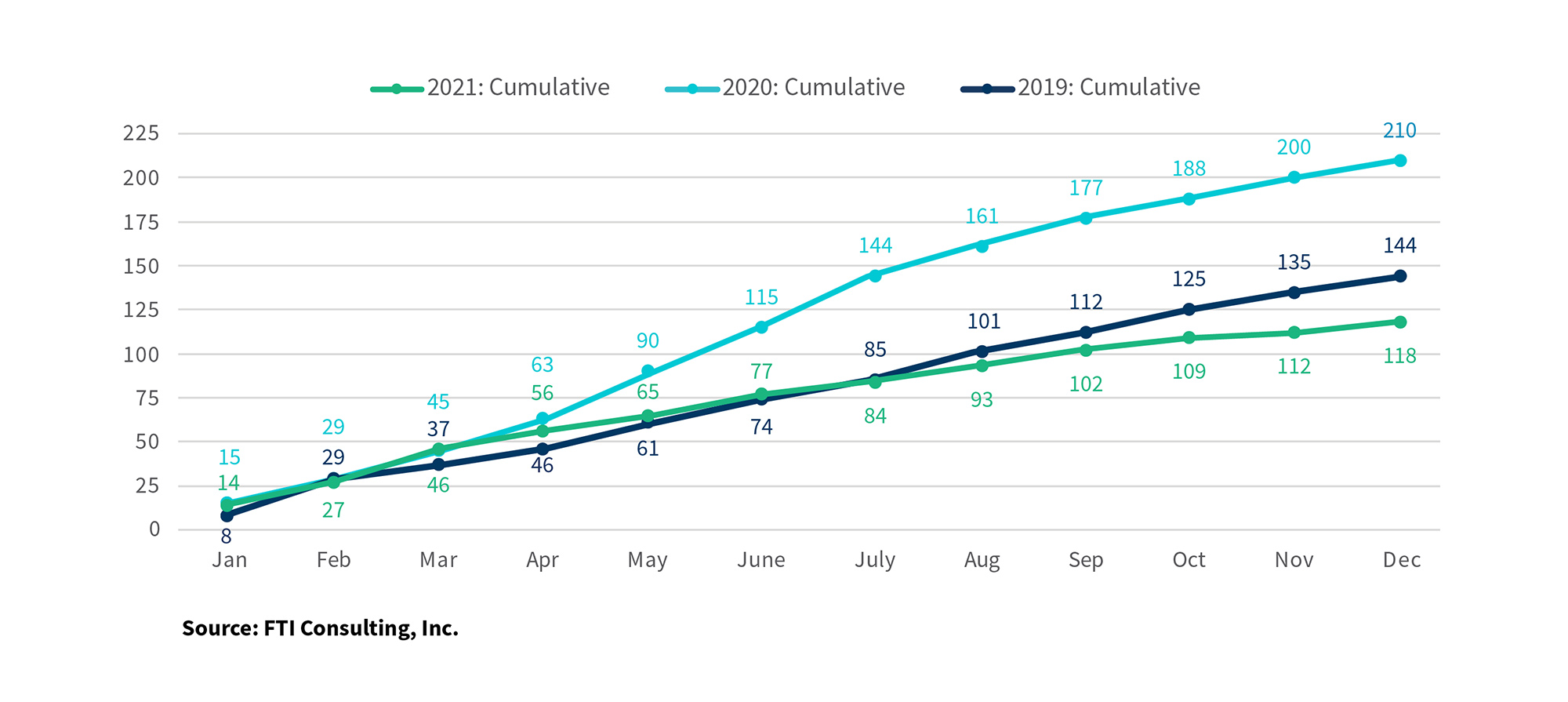

COVID-19 itself wasn’t a humbling event for forecasters — nobody could have seen it coming — but many events and outcomes that have transpired since COVID hit were utterly unexpected and often contrary to conventional wisdom or rational expectations. For instance, the plunge in bankruptcy filings (individual and commercial) to multi-decade lows amid the pandemic in 2020 and 2021 seems counterintuitive until one considers the unprecedented amount of financial assistance provided to American businesses and individuals. For the restructuring profession, base-case default rate forecasts made by the credit rating agencies in late 2020 for the year ahead proved to be far too high, though all anticipated a continuing economic recovery and a default peak in early to mid-2021.

Moreover, their base-case forecasts made at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in the summer and autumn of 2020 were wildly off the mark. Ultimately, the COVID-induced default cycle of 2020 did not conform to historical norms, and this upended conventional forecast models. While it was evident a year ago that the COVID-induced wave of defaults and restructurings was going to wash out sooner than most of us first expected, few experts anticipated such a sharp decline in large bankruptcy filings and debt defaults in 2021, particularly in the second half, with large corporate filings falling by 45% for the year (Exhibit 1) and rated debt defaults declining by nearly 70%.

Exhibit 1 - Cumulative Monthly Chapter 11 Filings

More broadly, most economists badly missed the call on the incredible strength of the consumer economy in 2021, the knock-on effects of chip shortages and supply chain issues, the surge of inflation and the Fed’s sooner-than-expected pivot on monetary policy — all major macroeconomic events.

We can count on one hand the number of market commentators who have consistently called it right since COVID struck, and they have mostly downplayed fundamentals and normative thinking in their analysis, instead focusing on policy effects, money flows and market momentum in making their calls. Those trying to impose their logic or historical norms when interpreting business and market developments that seem perplexing, such as the meme stock craze, are missing the point. The quantum of money that has inundated financial markets and household coffers since COVID began simply has overwhelmed all other considerations and offsets, with several trillion dollars of reserves and money flowing into the U.S. financial system and broader economy from the Federal Reserve and U.S. Treasury.

Furthermore, global liquidity remains abundant and there is little indication that these forces are going to dissipate in 2022, barring a wipeout event. Private credit is proving to be the tail that wags the dog in leveraged credit markets, with new multibillion-dollar funds becoming routine in 2021 and a few hundred billion of dry powder at year end1, most of it earmarked for leveraged lending, distressed lending and special situations. In the words of that famed economist Cyndi Lauper, money changes everything.

Omicron Shows that Most Americans Have Had it with COVID Restrictions

The Omicron variant of the COVID-19 virus came out of nowhere in late 2021 and quickly overwhelmed us, with reported new daily cases topping 200,000 as we ended the year, along with concerning but manageable upticks in hospitalizations and deaths. Omicron is 3x-5x more transmissible than the Delta variant but with milder symptoms for the vaccinated2. For the vast majority of Omicron cases, it is not much worse than a bad flu. Omicron dented holiday travel and large year-end gatherings, but most Americans were resolute and determined to carry on with their holiday season. In Manhattan, block-long lines outside many COVID testing clinics sometimes snaked past outdoor dining structures filled with diners, in a weird spectacle of contrasts.

The stunning theatre-run debut of Spider-Man: No Way Home, which grossed $253 million and sold 20 million tickets in North America in its opening weekend and nearly repeated that performance during Christmas week3, demonstrated that Omicron be damned, many Americans would risk it for a two-hour diversion in packed theatres. Critically, 62% of Spider-Man moviegoers were in the 18-35 age group4. Conversely, Steven Spielberg’s highly anticipated remake of West Side Story, an equally well-reviewed, theatre-only release, utterly bombed with a $10 million opening weekend gross and barely hit $25 million through Christmas5, as its targeted older audience failed to show up.

Therein lies the underlying story. Younger Americans, let’s say, arbitrarily, the under-40 crowd, are determined to move past COVID and resume their full lives. The over-40 crowd isn’t quite there yet and will likely continue to live more cautiously until COVID is mostly behind us. This has implications for the recovery in 2022. Activities frequented mostly by younger Americans, such as theme parks, concerts and gyms, should enjoy a nearly normal year in the absence of new virus variants. Cruise ships, casinos, international travel and other activities patronized more by older Americans may be another story, and normal won’t come any sooner than 2023. Several leading companies in these sectors recently had COVID-related financial covenant waivers or modifications extended into next year, as lenders have little intention of playing hardball at this juncture.

Even with the Omicron spike, state and local authorities in hard-hit areas have been vocal in emphasizing they intend to avoid COVID lockdowns, closures or other harsh restrictions, as the general public’s tolerance for such measures is fading fast. New strict lockdowns or curfews that were reimposed in some European countries seem very unlikely here, even sporadically. Instead, what we’ve seen are voluntary measures, with some businesses in COVID hot spots choosing to close (for various reasons) until the Omicron wave passes. Increasingly, Americans are viewing COVID-related hospitalizations and deaths as a scourge of the unvaccinated, and there is dwindling willingness to endure more collective hardship for their sake.

Inflation is the Biggest Risk to the Recovery and Markets in 2022

Can anyone be surprised that accelerating inflation has finally infiltrated the real economy after a prolonged period of extremely accommodative monetary policy and three rounds of stimulus payments to individuals? Several months ago, we suggested that outsized appreciation of financial assets, real estate and dubious asset classes since COVID hit is really a form of inflation that evades its conventional definition. Now price spikes have hit consumable goods, which is textbook inflation. It was bound to happen eventually, given the huge amounts of liquidity injected into the economy.

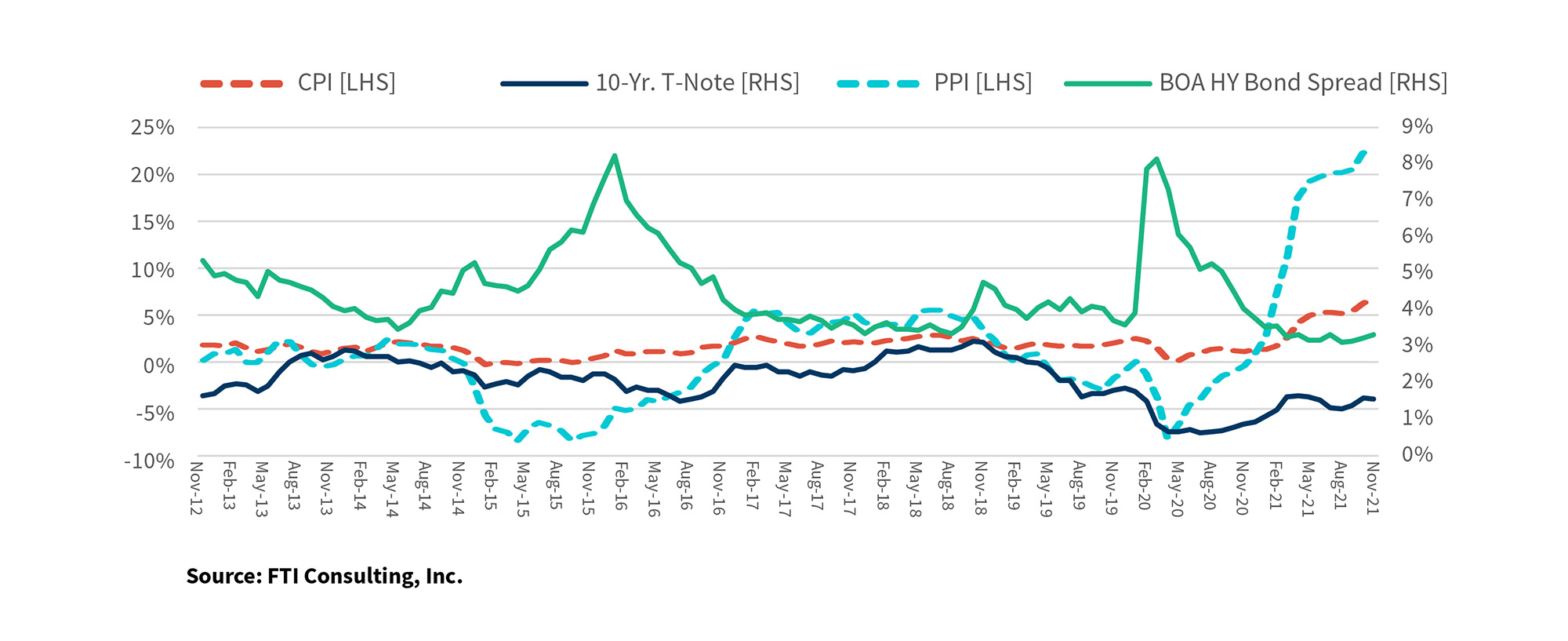

It’s hard to know how much to worry about inflation at this moment. It has been running hot for U.S. consumers since mid-2021, accelerating to the range of 5.0%-7.0% (YOY) over the last several months (Exhibit 2), more than double the rate of the last several years and well above the Fed’s target. Worse yet, the Producer Price Index (PPI; All Commodities) has spiked to 20% YOY increases since mid-year (Exhibit 2). The premise that high inflation is transitory has now been discarded by the Fed and most economists.

Exhibit 2 - Inflation Rate (YOY) vs. Fixed Income Yields

The news media has obsessed over the inflation story, and polling data says it’s a top concern for consumers (though you wouldn’t know it by their spending), but financial markets have ignored it. The 10-year Treasury note yield was lower at year-end than it was prior to the inflation spike while yields on B-rated and CCC-rated corporate debt have increased by just 50 bps and 100 bps, respectively, since mid-year and remain very low by historical measures, meaning that real yields fell considerably in 2021 and high-yield investors are not being compensated for the uptick in inflation and the higher credit risk it entails. Moreover, the price of gold, an inflation hedge for centuries, has barely moved since mid-year. Equity markets have, of course, shrugged it off too as they closed out 2021 at or near all-time highs. All of this is counterintuitive and unlikely to continue in 2022 if high inflation sticks around.

Inflation becomes truly problematic when it gets embedded in market expectations and pricing decisions, and we aren’t there yet. In response, the Fed has moved up and accelerated the wind-down of its huge monthly asset purchase program, which will now end by April 2022, with a series of base rate hikes expected to begin in mid-2022, at least six months ahead of prior expectations. There are two primary risks here. The Fed is widely viewed as reacting too late to address accelerating inflation as it was taking root, and so the horse is out of the barn and there is a risk that high inflation will be sticky for a while. Secondly, the Fed may have to act aggressively to quash inflation, and this runs the risk of inducing a slowdown or recession. Neither is a desirable outcome for the economy and markets. It will be a delicate balancing act, and the ho-hum response of financial markets to date would imply an expectation that the Fed will land the plane. But this outcome is far from certain.

The story of 2022 may not be the taming of COVID-19 but whether inflation can be tamed without disrupting the recovery. We’re not sure why markets are so sanguine when the likelihood of a bad outcome seems more than a longshot. It may not be a banner year for restructuring activity in 2022, but we expect it will be a considerable improvement compared to the last six months. That’s not saying much, but it’s as definitive as one can reasonably be as we enter the New Year near a low point for such activity.

Footnotes:

1: “Private Credit to Keep Up Frenzied Pace in 2022, but Macro Pressures Cloud Long-Term Picture,” Debtwire, December 31, 2021

4: https://www.thewrap.com/spider-man-no-way-home-587-million-debut/

5: https://www.cnbc.com/2021/12/26/west-side-story-is-officially-a-box-office-bomb.html

Related Insights

Related Information

Published

January 10, 2022

Key Contacts

Key Contacts

Global Chairman of Corporate Finance

Downloads

Most Popular Insights

- Beyond Cost Metrics: Recognizing the True Value of Nuclear Energy

- Finally, Pundits Are Talking About Rising Consumer Loan Delinquencies

- A New Era of Medicaid Reform

- Turning Vision and Strategy Into Action: The Role of Operating Model Design

- The Hidden Risk for Data Centers That No One is Talking About