Institutionalization of Crypto in Latin America

A Look at How Crypto and Blockchain Are Being Used in Latin America

-

July 25, 2023

-

In Europe, blockchain is seen generally as a value-added service. Disruptive, yes, but the next building block on the set path of payment facilitation and services. The conversation in Latin America is more radical. Blockchain is seen by some as an essential technology to operate outside the system, a way of protest or escape, against the permanent backdrop of inflation, corruption and political instability. It is the 21st century equivalent of stashing U.S. dollars under your pillow (which – it must be noted – still happens, especially in countries like Argentina and Venezuela). As one entrepreneur put it to me – “here, crypto is freedom”.

The question therefore arises of what happens when regimes appropriate crypto, and when blockchain – anti-establishment in its implementation here – is institutionalized.

Use Cases: Dissent Through Blockchain

Traditional financial services have fallen short for the majority of the continent. Around 70% of the population are unbanked or underbanked.1 It is no surprise then that crypto has been adopted with staggering velocity in Latin America, rising 200% from 2018 to over $500 billion in annual transactions.2,3

While in the United States, the industry has been damaged by the collapse of FTX and Silicon Valley Bank, and in Europe MiCA has brought crypto-assets under a tight regulatory framework, Latin America is still broadly a wild west and provides an unregulated lifeline for the highest number of crypto users in the world (by some estimates).4 The majority of low-cost transactions in the continent are cash-based.5 As such, crypto-currencies offer a significant route for greater security, transparency and connectivity.6 Below are predominant use cases in the region.

Preserving Value

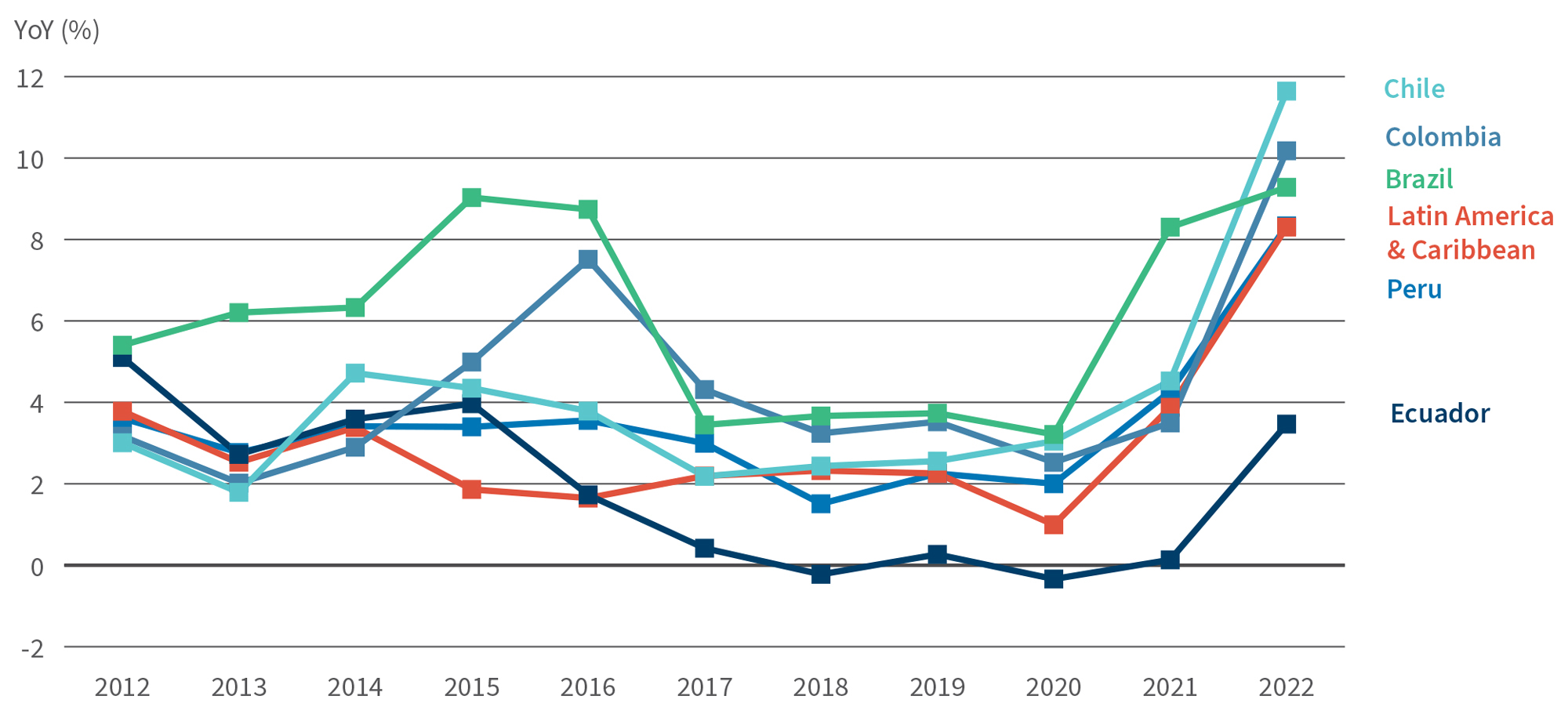

The rest of world is beginning to feel the full effect of inflationary pressure, but hyperinflation has been a reality in Latin American countries for decades. With an average inflation of over 10%, rising to past 100% in Argentina and over 400% in Venezuela, price volatility has eroded savings and forced consumers to look elsewhere to preserve value.7,8,9,10

Figure 1: Inflation, Average Consumer Prices.11

One option is to hold savings in US dollars, a method which can be complicated by restrictive foreign exchange controls. In Argentina, citizens have the option of either swapping pesos through their bank at the official rate and saving only up to US$200 a month, or resorting to buying ‘blue dollars’ on the black market, where they face much higher rates of exchange.12 As such, stablecoins – crypto-currencies pegged to fiat currencies – have become a way to avoid capital controls enforced by the government. For example, Reserve Dollar (RSV), pegged one-to-one to USD, has been launched with significant uptake in Venezuela, Argentina and Colombia in the last five years.13 More than a third of the continent have reported using stablecoins for daily purchases.14

Loans

Secondly, crypto loans have become popular in the face of interest rate hikes and a lack of trust in traditional financial institutions. Argentina’s interest rates are at nearly 100%, Venezuela stands at 60%, Mexico is at an all-time high, while Brazil holds the second highest real interest rate in the world.15,16,17,18

Customers are underserved. On the private side, it is not uncommon for banks to offer interest rates of several hundred percent.19 There is a significant lack of credit facilities in Latin America compared to similar-income regions like South Africa and Eastern Europe.20 To make matters worse, around half of the continent work in the informal economy and often lack the credit history to apply for institutional loans.21 As such, loan sharks and ‘gota a gota’ schemes proliferate.22,23

In this climate, crypto offers an alternative for individuals who need access to credit and wish to avoid governmental instability or informal exploitative deals. Crypto can offer up to 50% lower rates than traditional routes.24 Additionally, the tokenization of investment products, such as corporate bonds and real estate debts, has democratized assets which were previously only accessible for large investors.25 Decentralized Finance solutions in this space can ensure direct access to international markets (without any middlemen) and provide more predictable returns. For example, the crypto exchange Buenbit offers credits in Argentina via the stablecoin NuArs, while the lending platform Ledn has provided over US$500 million in USD coin (USDC) credits to customers in Latin America.26,27

Remittances

A third use case popular in the region is cross-border transactions. Remittance payments are a huge market in Latin America, accounting for around US$150 billion a year.28 In Colombia, remittances have become a greater source of dollar revenue than coal.29

Traditional channels for remittances require intermediaries (payment processors, banks etc.) and as such can be slow and expensive. In contrast, crypto-payments need only a smartphone and Internet connection – no bank account – and can be tracked and verified easily on the blockchain. As such, accessibility and transparency have driven adoption: for example, in 2022, Bitso processed US$3.3 billion in remittance payments between the United States and Mexico.30

The Dark Side of Crypto

The issue with creating a vehicle which operates outside the system is that while it can be used as a legitimate mechanism in autocratic or corrupt regimes, it can equally be used for corrupt purposes to evade legitimate state controls. Activity which was previously cash-based has shifted online. Most major criminal organizations and gangs in Latin America have been reported using crypto-currencies to exploit weak financial regulations and avoid detection and asset seizures.31

For example, the international criminal gang Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) demands payment in Bitcoin for cocaine shipments from Mexico to the United States.32 Brazil’s largest criminal group, Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC), have made transactions of up to US$7.8 million in crypto-currencies.33 The Mexican-based syndicate Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación (CJNG) was caught laundering approximately US$30 million over Binance, the world’s main crypto-exchange.34

The issue for the crypto-industry therefore becomes how to walk the tightrope between anonymity and accountability, protecting its users while holding them responsible for criminal usage.

Institutionalization: The State Reacts

As we have seen, crypto-currencies are used in Latin America both for criminal activities and for currency substitution by citizens to avoid state measures like capital controls and tax collections. In response, governments have been forced to act.

Prohibition

On one end of the spectrum of policy response is banning crypto-currency altogether. In 2014, Bolivia specified that all currencies not regulated by the government – including virtual currencies – were illegal.35 In the same year, Ecuador banned Bitcoin as a payment method.36 Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Venezuela have restricted the use of crypto-currencies in daily merchant and retail trades.37

The issue with this response is its effectiveness. Banning crypto is like attempting to ban the Internet. Policies of this kind serve only to drive usage underground and make crypto more anti-establishment, like we have seen in China, thus doing the opposite of intended.38

Regulation

The second policy option is to bring crypto under the umbrella of the state through regulation. This can help solve some of crypto’s headaches: for example, both Brazil and Argentina have policies in place to collect income tax through crypto-currencies.39,40

Regulation is essential. Crypto is fundamentally a speculative asset, with no backing assets or central bank credibility.41 Unregulated, it is prone to scams, exploitation, a lack of processes such as refunds and chargebacks, and thus poses significant risk for individuals who rely on it as a lifeline.42 In 2021, GFI reported that only six countries in the region had enacted “laws and regulations”.43 Bringing crypto in from the cold through responsible institutionalization is crucial as the ecosystem grows, and will help to build trust, infrastructure and education.

Central bank digital currencies (“CBDCs”) – digital versions of a country’s fiat currency, issued by the central bank – are increasingly being used to harness the benefits of blockchain technology while implementing standards and achieving public policy objectives. In Colombia, President Gustavo Petro has expressed his support for a digital currency as a way of curbing tax evasion (an estimated 8% of GDP).44 CBDCs are operational in Jamaica, Bahamas and the ECCU, while Brazil, Uruguay and Mexico among others have taken preliminary steps.45,46

Deregulation

Governments have also been known to adopt crypto for more nefarious reasons. As we saw after Russia was cut off from SWIFT following the invasion of Ukraine, crypto can be used to circumvent Western currency markets and is an effective tool for money-laundering havens and corrupt regimes.47

Under President Nicolás Maduro, the Venezuelan government has been accused of financing itself through narcotics and the illegal sale of oil and gold.48 Military leaders must launder these funds, and with international sanctions, the rapid devaluation of the Venezuelan bolívar and cash shortages, crypto has become an advantageous state mechanism due to its opacity. In 2018, Venezuela launched the Petro, the state’s official digital currency. Venezuela’s crypto market now accounts for nearly US$40 billion and is growing quickly.49

Market Spotlight: Brazil

Brazil provides a useful template of positive involvement by the public sector. Customers in Brazil – a market with a stronger economy – use crypto-currency more as a speculative investment than for the use cases we identified above.50 Regulation has enabled the ecosystem to develop responsibly while promoting private sector initiatives from players including MasterCard, Nasdaq, and Mercado Libre’s MBRL, the first Brazilian stablecoin.51 Stablecoins account for over a quarter of retail trades in the country.52 Brazil has both the highest crypto-currency adoption rate and the most Bitcoin ETFs in the continent.53,54 In December 2022, the “Brazilian Crypto-Assets Law” was approved to regulate virtual asset services and tackle fraud.55 Regulation has facilitated public sector efforts like AML and asset tracing, enabling successful criminal investigations and federal police raids.56

Purposeful deregulation is a tactic in a rising number of jurisdictions.57 Paraguay, an established money laundering haven, has positioned itself as a ‘Bitcoin hub’ for a variety of alleged reasons, including:

- Attracting investment from high-net-worth individuals, especially those fleeing prosecution;58

- Protecting high-ranking politicians, among them former president Horacio Cartes, from U.S. inquiries;59 and

- Facilitating interactions with terrorist groups such as Hezbollah.60

In amongst jurisdictions of this type, El Salvador is by far the most famous. In 2021, it became the first country on the planet to adopt crypto as a national currency by making Bitcoin legal tender.61 This followed a move ten years previous, in 2001, to adopt the U.S. dollar as currency and phase out the local colón.62 The uptake of Bitcoin – an alternate currency substitution – can be seen as the next step in this dollarization; it is a development termed ‘cryptoization’ by the IMF.63 On the face of it, it was implemented with the aim of improving financial inclusion (70% of the population is unbanked), reducing dependency on the United States and lowering transaction costs for remittances, which account for more than a quarter of GDP.64,65

In practice, however, the Bitcoin law has attempted to remove freedom of currency and mandate that “every economic agent must accept bitcoin as payment.”66 Rather than crypto being anti-establishment, here is an example of the state forcing it onto the public. But it is almost impossible to dictate mass adoption. The effects have been underwhelming: less than 2% of remittances are sent via digital wallets, and 80% of Salvadoran firms do not accept Bitcoin as a medium of exchange.67,68 Instead, the adoption of bitcoin has exposed the country to the volatility of the crypto market. 10 months after adopting it, Bitcoin crashed and the $100 million in Treasury funds which President Nayib Bukele (“Bukele”) had invested lost around 60% of their value.69 We have spoken of the risks of runaway inflation in traditional Latin American currencies; this catastrophe recalls the quote, “better the devil you know…”

In addition, El Salvador has been accused of using crypto to fund gangs such as MS-13 and secure sources of cash separate to the IMF.70 There is a strange paradox here. Bukele has publicly said El Salvador is a refuge for “people escaping censorship” and the country offers citizenship based crypto-currency investments.71 The country has therefore positioned itself as subversive – an ‘anti-establishment establishment’ – appealing to those who wish to escape prohibition and state oppression abroad, despite the reality that Bukele runs an oppressive regime which has crushed individual liberties.72 It is an optics game. And it has worked. The adoption of Bitcoin has diverted attention away from Bukele’s autocratic tendencies and human rights abuses, positioning him as an innovative ‘tech bro’.73 Tourism has soared by 95% and he has courted support from Silicon Valley to Wall Street.74,75

The gamble has surpassed expectations in other regards – Bloomberg had listed El Salvador as the country most likely to default on its debt, and Western media (aside from some crypto-enthusiasts) has been overwhelmingly negative.76 However, in January 2023, El Salvador paid its US$800 million debt in full.77 The fiscal deficit was 2.7% of GDP in 2022, down 46% from the previous year.78 In February 2023, Moody’s outlook for El Salvador changed to ‘stable’.79 The country has been the top outperformer in Citi’s emerging market sovereign bond index this year.80 By all accounts, the crypto-winter last year was unfortunate timing, but the cat is not out the bag yet.

Conclusion

As we have seen, the main challenge for Latin America is how to transition the usage of crypto-currencies from an underground phenomenon to one which is approved and responsibly managed by the state. I recently attended Holland & Knight’s Foro Blockchain Law event, where it was encouraging to see the advances in regulation across the region.81 The benefits of crypto-currencies in the continent are clear; regulation will be the key to harness these benefits while minimizing its irresponsible and illegal applications.

Footnotes:

1: Bill Briggs, “‘We have to solve the problem’: How three fintechs are boosting financial inclusion in Latin America”, Microsoft (2023), [Link]

2: [Link]

3: Juan Abad, “Conoce algunos sectores de Latinoamérica donde esperan que la tecnología blockchain tenga un impacto significativo”, Cointelegraph en Español (2023), [Link]

4: Eclac, “Top 20 Crypto Statistics for Latin America”, Eclac (2022), [Link]

5: FIS, “Global Payments Report 2023”, FIS (2023), [Link]

6: Helen Partz, “Colombia to prevent tax evasion with national digital currency: Report”, Cointelegraph (2022), [Link]

7: Statista Research Department, “Inflación en América Latina – Datos estadísticos”, Statista (2023), [Link]

8: Mayela Armas, “Venezuela Inflation accelerates to 8.2% m/m in August”, Reuters (2022), [Link]

9: Reuters in Buenos Aires, “Argentina’s inflation rate soars past 100%, its worst in over 30 years”, The Guardian (2023), [Link]

10: Trading Economics, “Venezuela Inflation Rate”, Trading Economics (2023), [Link]

11: World Development Indicators, World Bank (2023), [Link]

12: Chainalysis Team, “Latin America’s Key Crypto Adoption Drivers: Storing Value, Sending Remittances, and Seeking Alpha”, Chainalysis (2022), [Link]

13: Reserve, “An introduction to Reserve”, Reserve (n.d), [Link]

14: Andrés Engler, “Half of Latin Americans Have Used Cryptocurrencies, Mastercard Survey Shows, CoinDesk (2022), [Link]

15: CNN, “Argentina raises interest rate to 97 per cent as it struggles to tackle inflation”, 9News (2023), [Link]

16: Trading Economics, “Venezuela Interest Rate”, Trading Economics (n.d.), [Link]

17: Banco de México, “Anuncio de Política Monetaria”, Banco de México (2022), [Link]

18: Natália Scalzaretto, “Brazil’s real interest rate world’s second-highest after Selic bump”, The Brazilian Report (2021), [Link]

19: Marina Lammertyn, “Crypto Loans Are Booming in Latin America Amid Runaway Bank Rates and Inflation”, Yahoo!finance (2022), [Link]

20: Preetam Kaushik, “How crypto is financially empowering women in Latin America, Culture 3 (2023), [Link]

21: Organización Internacional del Trabajo (OIT), “Economía informal en América Latina y el Caribe”, OIT (n.d.), [Link]

22: [Link]

23: Shane Sullivan, “Loan Sharks Circle as Latin America Reels From Pandemic”, Insight Crime (2021), [Link]

24: Marina Lammertyn, “Crypto Loans Are Booming in Latin America Amid Runaway B Rates and Inflation”, Yahoo Finance (2022), [Link]

25: Cointelegraph, “The Drivers Behind Cryptocurrency Adoption in Latin America in 2022”, Binance (2022), [Link]

26: Ámbito, “Qué son y para qué sirven las NuARS, la criptomoneda que sigue el valor del peso argentino”, Ámbito (2022), [Link]

27: Marina Lammertyn, “Crypto Loans Are Booming in Latin America Amid Runaway B Rates and Inflation”, Yahoo Finance (2022), [Link]

28: The Dialogue, “Sustained Remittance Growth in 2022”, The Dialogue (2022), [Link]

29: Valerie Cifuentes, “Remittances to Colombia Surpass Coal As Dollar-Revenue Source”, Bloomberg Línea (2022), [Link]

30: Albert Brown, “Ripple Transacts $3.3B Between Mexico and US With Bitso Using XRP”, The Crypto Basic (2023), [Link]

31: Diego Oré, “Latin American crime cartels turn to cryptocurrencies for money laundering”, Reuters (2020), [Link]

32: Infobae, “Los cartels mexicanos encontraron una nueva forma de lavar dinero: con criptomonedas”, Infobae (2020), [Link]

33: Farah and Richardson, “The Growing Use of Cryptocurrencies by Transnational Organized Crime Groups in Latin America”, Georgetown Journal of International Affairs (2023), [Link]

34: Julian Walling, “International drug conspiracy used Binance to launder millions, DEA probe finds”, BusinessNews (2022), [Link]

35: Freeman Law, “Bolivia and Cryptocurrency”, Freeman Law (n.d.), [Link]

36: Freeman Law, “Ecuador and Cryptocurrency”, Freeman Law (n.d.), [Link]

37: Eclac, “Top 20 Crypto Statistics for Latin America”, Eclac (2022), [Link]

38: Huang, Ghosh and Huang, “Chinese Users of the Binance and FTX Exchanges Show Holes in Beijing’s Crypto Ban”, Bloomberg (2023), [Link]

39: Andrés Engler, “Buenos Aires City to Allow Residents to Make Tax Payments With Crypto”, CoinDesk (2023), [Link]

40: Cassio Gusson, “Brazil’s Federal Revenue now requires citizens to pay taxes on like-kind crypto trades”, Cointelegraph (2022), [Link]

41: Appendino et al, “Crypto Assets and CBDCs in Latin America and the Caribbean: opportunities and Risks”, IMF eLibrary (2023), [Link]

42: PetAppendino et al, “Crypto Assets and CBDCs in Latin America and the Caribbean: opportunities and Risks”, IMF eLibrary (2023), er Howson, “Bitcoin: El Salvador’s failed experiment has important lessons”, Context (2022), [Link]

43: Scott Mistler Ferguson, “Digital Wild West: Latin America Unprepared for Crypto-Crime”, InSight Crime (2022), [Link]

44: Helen Partz, “Colombia to prevent tax evasion with national digital currency: Report”, Cointelegraph (2022), [Link]

45: Appendino et al, “Crypto Assets and CBDCs in Latin America and the Caribbean: opportunities and Risks”, [Link]

46: David Feliba, “The state of Central Bank Digital Currencies in Latin America”, Fintech Nexus News (2022), [Link]

47: Lucas Mearian, “After the SWIFT ban, can Russia find other routes for its money – including crypto?”, Computerworld (2022), [Link]

48: Celina Realuyo, “Disrupting the Illicit Economy that Sustains the Maduro Regime”, Diálogo Américas (2020), [Link]

49: Chainalysis Team, “Latin America’s Key Crypto Adoption Drivers: Storing value, Sending Remittances, and Seeking Alpha”, Chainalysis (2022), [Link]

50: Crystal Kim, “Different use cases for crypto around the world spur divergent crypto markets”, Axios (2022), [Link]

51: Leo Schwartz, “´I finally found my tribe’: Inside Latin America’s booming crypto testing ground“, Fortune Crypto (2022), [Link]

52: Chainalysis Team, “Latin America’s Key Crypto Adoption Drivers: Storing value, Sending Remittances, and Seeking Alpha”, Chainalysis (2022), [Link]

53: Mathew Di Salvo, “Latin America’s Biggest Investment Bank Just Launched a Stablecoin on Polygon”, Yahoo Finance (2023), [Link]

54: Scott Mistler Ferguson, “Digital Wild West: Latin America Unprepared for Crypto-Crime”, InSight Crime (2022), [Link]

55: Bexs, “New regulation for crypto market in Brazil”, Bexs (2023), [Link]

56: Rodrigo Tolotti, “Brazilian Federal police Raids 6 Crypto Exchanges in Money Laundering Investigation”, CoinDesk (2022), [Link]

57: Farah and Richardson, “The Growing use of Cryptocurrencies by Transnational Organized Crime Groups in Latin America”, Georgetown Journal of International Affairs (2023), [Link]

58: DiarioBitcoin, “Gobierno de Paraguay respalda creación de centro de minería de criptomonedas”, DiarioBitcoin (2018), [Link]

59: U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Sanctions Paraguay’s Former President and Current Vice President for Corruption”, U.S. Department of the Treasury (2023), [Link]

60: Id

61: Renteria et al., “In a world first, El Salvador makes bitcoin legal tender”, Reuters (2021), [Link]

62: Juan Aznárez, “El Salvador adopta el dólar como moneda nacional para intentar salvar su economía”, El País (2021), [Link]

63: Appendino et al, “Crypto Assets and CBDCs in Latin America and the Caribbean: opportunities and Risks”, IMF eLibrary (2023), [Link]

64: Henri Arslanian et al., “El Salvador’s law: a meaningful test for Bitcoin”, PWC (20219, [Link]

65: Irma Cantizzano, “El Salvador tiene el mayor peso de remesas em América Latina”, El Economista (2022), [Link]

66: Asamblea Legislativa de la República de El Salvador, Decreto N°57, (2021), [Link]

67: Pablo Balcáceres, “Why Bitcoin Is Losing Its Shine in El Salvador”, Bloomberg Línea (2022), [Link]

68: Alvarez et al., “Are Cryptocurrencies Currencies? Bitcoin as Legal Tender in El Salvador”, NBER (2023), [Link]

69: Hanke and Hofmann, “The veredict Is in for El Salvador’s Bitcoin Experiment: It Failed”, National Review (2022), [Link]

70: David Morris, “Bukele’s MS-13 Double Bind”, CoinDesk (2021), [Link]

71: Glenda González, “Bitcoin y el surf los atraen: 1 millón de turistas visitó El Salvador en lo que va de 2023”, CriptoNoticias (2023), [Link]

72: Amnesty International, “El Salvador: President Bukele engulfs the country in a human rights crisis after three years in government”, Amnesty International (2022), [Link]

73: Ciara Nugent, “El Salvador Is Betting on Bitcoin to Rebrand the country – and Strengthen the President’s Grip”, Time (2021), [Link]

74: J.R., “El bitcoin hace que el turismo crezca un 95% en El Salvador”, Expreso (2023), [Link]

75: Glenda González, “Nayib Bukele: Bitcoin le dio una nueva imagen a El Salvador”, CriptoNoticias (2023), [Link]

76: Sydney Maki, “Historic Cascade of Defaults Is Coming for Emerging Markets”, Bloomberg (2022), [Link]

77: Maki and Vizcaino, “Bukele dice que El Salvador pagó US$800M de bonos; evita default”, Bloomberg (2023), [Link]

78: Uveli Alemán, “Déficit fiscal se reduce 46% en 2022 por más ingresos y caída de inversión”, El Mundo (2023), [Link]

79: [Link]

80: [Link]

81:Holland & Knight, “Foro Blockchain Law: Colombia 2023”, Holland & Knight (2023), [Link]

Published

July 25, 2023

Key Contacts

Key Contacts

Senior Consultant