Sources of Funds - Mexico

Examining Money Laundering Risks and Source of Funds Challenges for Mexican Entities

-

July 05, 2023

DownloadsDownload Article

-

Mexico has long been identified as a significant-risk money laundering jurisdiction, stemming principally from activities most often associated with organized crime. During 2022, Mexico’s Financial Intelligence Unit received approximately 35.7 million reports and notices related to the current anti-money laundering regulation for financial and non-financial entities.1 This number highlights the importance of the anti-money laundering regulatory environment in Mexico, where financial institutions and companies that operate in selected industries face ever-increasing compliance challenges daily, including the appropriate identification of beneficiary owners and source of funds of their customers and shareholders, as well as other third parties.

Within this context, this article briefly analyzes the challenges faced by Mexican entities in relation to potential legal entity misuse and source of funds practical considerations.

Enhanced KYC Considerations in Mexico – Legal Structures and Source of Funds

With more and more companies interacting in a globalized market, organizations are facing complex challenges accentuated by the increasing inherent risk of doing business with inadequate business partners. While these potentially risky relationships may come in different forms depending on the business setting, the perspectives and questions to be answered are twofold:

- Do companies have a clear understanding and identification of the true owners of the legal entity with whom they are conducting business?, and,

- Are companies correctly identifying and assessing the third-parties’ source of funds as applicable in their business context?

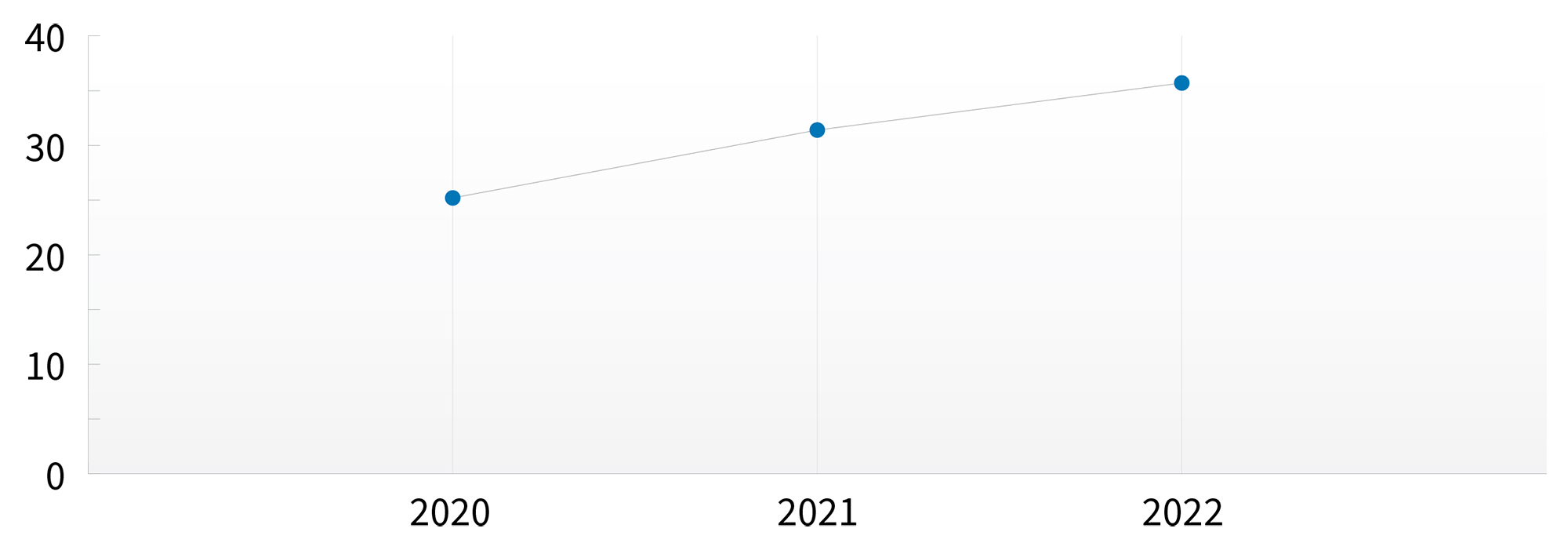

During 2022, Mexico’s financial and non-financial entities that fell under the scope of the Federal Law for the Prevention and Identification of Operations with Illicit Resources2 sent 35.7 million reports and notices to the Financial Intelligence Unit, up 13% from 2021.3 This law, in addition to other documents that derive from it, establishes the obligation of financial institutions and other designated non-financial businesses and professions that conduct vulnerable activities (“DNFBP”) to adopt and implement policies, procedures, and controls to prevent and detect money laundering and terrorist financing activities.4 The National Banking and Securities Commission (“CNBV”) is the authority responsible for overseeing and enforcing these regulations for financial institutions,5 whereas the Tax Administration Service (“SAT”) is responsible for overseeing and enforcing these regulations for DNFBP.6

Figure 1 - AML Reports and Notices Received by the FIU (in Millions)

Source: Own elaboration with data from FIU 2022.7

In line with the authors’ perspectives, there are a number of risks that have been previously identified in Mexico by the Financial Action Task Force (“FATF”), an international organization that sets global standards for anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing.8 As a member of the FATF, Mexico is subject to regular evaluations to assess its compliance with the organization's standards. The results of the last mutual evaluation conducted by the FATF suggest that companies and financial institutions in Mexico may face significant risks due to high corruption, organized crime (primarily drug trafficking), limited understanding of the misuse of legal entities by companies and financial institutions, and the often limited identification of the resources’ ultimate beneficiary owner (“UBO”).9

Risks Derived From Legal Entity Structure and Ownership

Mexico has long been identified as a high-risk jurisdiction for money laundering, derived principally from activities most often associated with organized crime, such as drug trafficking, extortion, corruption and tax evasion.10 According to a report from Global Financial Integrity, Mexico is one of the top countries in Latin America participating in illicit fund outflows, ranked by dollar value.11

According to the 2022 “Report On The State Of Effectiveness And Compliance With The FATF Standards,” although about half (52%) of FATF member countries have the necessary laws and regulations to understand and assess the risks, as well as verify the beneficial owners or controllers of companies (legal entities and arrangements), only 9% of member countries are meeting the effectiveness requirements of these controls.12 Taking this into perspective, although Mexico’s regulations require companies to identify and verify the UBOs of legal entities, the risk of working with shell companies is ever-present and failure to identify and verify UBOs can lead to an increased risk of indirectly participating in a network of corruption, fraud, or money laundering. Recent examples of large schemes involving corruption and shell corporations include the current trial against Mexico’s former Secretary of Public Security Genaro Garcia Luna involving damages of approximately US$750 million,13 and the Odebrecht case involving the payment of bribes to former PEMEX president Emilio Lozoya for an approximated alleged amount of up to US$10.5 million.14

From a business context perspective, financial institutions and companies who engage in activities that are considered DNFBPs are at risk of conducting transactions with high-risk third-parties, and thus must travel the extra mile to ensure compliance with regulations.15 According to the latest National Risk Evaluation, published in 2020 by the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit, the higher-risk financial institutions include commercial, investment and development banks, foreign currency exchanges, regulated finance companies (“SOFOM” in Spanish), cooperative societies, among others.16 Higher-risk activities which are considered DNFBPs include the sale of any type of vehicles, jewelry and metals, armored vehicles, loans, sale of real estate, among others.17

A challenge for all of these entities is the use of nominee directors or shareholders by third-parties to conceal the identities of UBOs. This is a common tactic in Mexico and other countries, as it allows individuals or companies to maintain control of an entity while obscuring the beneficial ownership of assets and transactions.18

An additional challenge in the local business setting is related to the availability of legal entity structure public information. Within this context, the Mexican General Law of Mercantile Companies obliges all companies to register their minutes of assembly, share titles and bylaws in the correspondent Public Registry Office in the municipality where the company was constituted.19 However, this represents a limitation for the availability of data, since the information is not centralized, and it is often hard and cumbersome to access.

To address these challenges, Mexican regulators are working to improve the transparency and accuracy of UBO information. Starting on January 1, 2022, Mexico's tax authority launched a new registry for beneficial owners, requiring legal entities, trusts and any legal vehicle or figure incorporated under the laws of Mexico and registered before the Tax Administration Service to maintain as part of their tax accounting registries information regarding their beneficial owners.20 This is a step in the right direction, but more needs to be done to ensure that compliance measures are being implemented effectively.

As a closing comment, and in light of the importance of Mexico’s economy and geographical location, the challenges associated with legal entity misuse and the hiding of beneficiary owners are not only domestic. The United States, through the Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”), and other countries have imposed various sanctions on Mexico in recent years, with a particular focus on targeting individuals and entities involved in drug trafficking and money laundering activities.21 Mexican financial institutions and companies that engage in business with flagged individuals or entities can face significant consequences, including but not limited to monetary and reputational damage.

Source of Funds Considerations

While source of funds considerations are a key element of appropriate risk management, they vary among financial institutions and DNFBP, bearing in mind that they operate in fundamentally distinct industries and business environments. In connection with the risks derived from legal entity structures, it is important to indicate that legal entity and UBO diligence procedures are intrinsically intertwined with source of funds diligence procedures. Typically, obtaining information about the client's source of funds is a part of the client’s due diligence procedure, where the objective is understanding where customers have obtained the money that they are using to conduct transactions and make investments, considering that money launderers and other criminals use increasingly sophisticated methodologies to conceal the source of illegal money. For clarity purposes, we will briefly discuss practical source of funds (“SoF”) and source of wealth (“SoW”) implications for financial institutions and DNFBP separately.

Financial Institutions

Firstly, as defined in a Wolfsberg Group FAQ document, SoW assessment seeks to identify how a customer accumulated their wealth and SoF information provides an understanding of how and for what purpose an account is going to be funded.22

In the framework of financial institutions in Mexico, as part of the licensing process for certain types of these institutions, such as financial technology, SOFOM and banks, regulators require them to engage independent third-parties to conduct a SoF review to verify the origin of the shareholders’ funds.23, 24, 25 In addition to this, on the operational side of financial institutions, they generally conduct SoF and SoW diligence for their clients at two moments, at client onboarding and subsequently at a periodic review depending on the risks presented by such client. For example, higher-risk clients may require enhanced due diligence measures, such as additional documentation, background checks, and ongoing monitoring. According to the Wolfsberg Group FAQ document, these exercises should not be considered only a documentary exercise, and must include corroborations with available public sources as needed.26

In the Mexican context, financial institutions, especially those that provide private banking services, focus on high-risk clients for SoF and SoW reviews, the main challenge that these institutions face is the limited manpower when it comes to comprehensively evaluating an important number of medium to high-risk clients. The lack of attention to detail in this type of procedure may give rise to incomplete client files and breaches in the anti-money laundering compliance program, ultimately impacting the institutions’ bottom line in the form of penalties from regulators and reputational damage.

Non-Financial Institutions - DNFBP

According to a FATF report, criminals gravitate towards sectors that apply or are believed to apply less comprehensive regulation and mitigation measures, or where supervision is found to be lacking.27 This is especially important in the Mexico setting, considering that the regulation for DNFBP is, at a glance, more lenient than regulation faced by financial institutions. For example, FATF states that in real estate transactions in many countries, there are limited means to determine adequate, accurate, and up-to-date information on the beneficial owner[s] and the related SoF.28

Additionally, the relatively high-value of properties may require multiple types of financing, which may complicate efforts to identify the SoF. Different types of DNFBP will face different SoF challenges, but at its core, DNFBP must pay special attention on implementing a tailored customer risk and overall risk-based assessment that allows them to determine when a comprehensive SoF and SoW exercise is required, taking into account a combination of factors, including but not limited to customer and product type, payment channels and geographies.

How Can We Help

FTI Consulting’s Risk and Investigations practice (“R&I”) in Mexico provides accurate and definitive insight into the registered owners of legal entities. In addition to custom background checks, FTI Consulting’s team can provide companies with tailored on-site searches at the municipalities where companies have been constituted to ensure Clients have a clear understanding of the structure of relevant legal entities. In regards to anti-money laundering requirements, in addition to regulatory and compliance assessments, FTI Consulting can provide insight into the verification of source of funds for financial and non financial institutions, both for licensing (e.g. for new financial entities) and operational purposes (e.g. customer periodic verification). Our unique and skilled team of multilingual professionals provides a multidisciplinary approach to critical investigations, combining functional expertise with a deep understanding of compliance policies and investigative processes. FTI Consulting’s team combines the skills and experiences of lawyers, forensic accountants, former government officials and regulators, anti-corruption investigators, computer forensic and enterprise data specialists.

Footnotes:

1: “Informe de Actividades.” Unidad de Inteligencia Financiera (December 2022). https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/792041/Informe_Diciembre_2022.pdf.

2: “Ley Federal para la Prevención e Identificación de Operaciones con Recursos de Procedencia Ilícita.” Camara de Diputados del H. Congreso de la Union (May 20, 2021). https://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/LFPIORPI_200521.pdf.

3: “Informe de Actividades.” Unidad de Inteligencia Financiera (December 2022). https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/792041/Informe_Diciembre_2022.pdf.

4: “Obligaciones contempladas en la LFPIORPI para quienes realicen actividades vulnerables.” Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público (last accessed June 20, 2023). https://sppld.sat.gob.mx/pld/interiores/obligaciones.html.

5: National Banking and Securities Commission (Mexico). Latin Lawyer (last accessed June 20, 2023). https://latinlawyer.com/insight/ll-regulators/regulators/organization-profile/national-banking-and-securities-commission-mexico.

6: Unidad de Inteligencia Financiera (last accessed June 20, 2023). https://uif.gob.mx/es/uif/nacional

7: “Informe de Actividades.” Page 4. Unidad de Inteligencia Financiera (December 2022). https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/792041/Informe_Diciembre_2022.pdf.

8: “Anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing measures – Mexico – Follow-up Report & Technical Compliance Re-Rating.” (May 12, 2022). https://www.fatf-gafi.org/en/publications/Mutualevaluations/Fur-mexico-2022.html.

9: Ibid.

10: Corruption Perceptions Index (2022).” Transparency International (last accessed June 20, 2023). https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2022/index/mex.

11: “Illicit Financial Flows to and from 148 Developing Countries: 2006-2015.” Global Financial Integrity (January 2019). https://gfintegrity.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/IFF-Report-2019_11.18.19.pdf.

12: FATF, Report on the State of Effectiveness Compliance with FATF Standards, April 2022, Paris, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/content/dam/fatf-gafi/reports/Report-on-the-State-of-Effectiveness-Compliance-with-FATF-Standards.pdf.coredownload.pdf.

13: Elias Camhaji and Zedryk Raziel. “Mexico and US on parallel course to probe fortune of ex-drug czar Garcia Luna.” El País (January 30, 2023). https://english.elpais.com/international/2023-01-30/mexico-and-us-on-parallel-course-to-probe-fortune-of-ex-drug-czar-garcia-luna.html.

14: Pedro Hiriart. “Caso Odebrecht: Difieren audiencia de Emilio Lozoya; será en marzo.” El Financiero (January 17, 2023). https://www.elfinanciero.com.mx/nacional/2023/01/17/caso-odebrecht-defensa-de-emilio-lozoya-insistira-en-criterio-de-oportunidad-en-nueva-audiencia/.

15: “Evaluación Nacional de Riesgos: 2020.” Gobierno de Mexico; Secretaria de Hacienda y Creditor Publico (September 2020). https://www.pld.hacienda.gob.mx/work/models/PLD/documentos/enr2020.pdf.

16: Ibid.

17: Ibid.

18: FATF – Egmont Group (2018), Concealment of Beneficial Ownership , FATF, Paris, France. https://www.fatf-gafi.org/en/publications/Methodsandtrends/Concealment-beneficial-ownership.html.

19: “Ley General de Sociedades Mercantiles.” Cámara de Diputados. 2018. https://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf_mov/Ley_General_de_Sociedades_Mercantiles.pdf.

20: “Mexico: Beneficial owner records – New obligation for all legal entities and vehicles.” Baker McKenzie (March 2, 2022). https://insightplus.bakermckenzie.com/bm/tax/mexico-beneficial-owner-records-new-obligation-for-all-legal-entities-and-vehicles.

21: “Treasury Works with Government of Mexico to Sanction Corrupt Police Official and Other Individuals Supporting CJNG.” U.S. Department of the Treasury (June 2, 2022). https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0803.

22: “Wolfsberg Group Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): Source of Wealth and Source of Funds (Private Banking/Wealth Management).” The Wolfsberg Group (2020). https://db.wolfsberg-group.org/assets/a27f9bf6-b4a8-41d2-a390-6f1aaf797241/Wolfsberg%20SoW%20and%20SoF%20FAQs%20August%202020%20(FFP)_1.pdf.

23: “Disposiciones de carácter general aplicables a las instituciones de crédito.” Gobierno de Mexico; Secretaria de Hacienda y Creditor Publico (January 13, 2023). [Link].

24: “FIU Legal Framework, General Provisions.” Gobierno de Mexico; Secretaría de Haciendo y Crédito Público, (January 12, 2016). https://www.gob.mx/shcp/documentos/uif-marco-juridico-disposiciones-de-caracter-general.aspx.

25: “Disposiciones de carácter general aplicables a las Instituciones de Tecnología Financiera.” Gobierno de Mexico; Secretaria de Hacienda y Creditor Publico (December 15, 2021). [Link].

26: “Wolfsberg Group Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): Source of Wealth and Source of Funds (Private Banking/Wealth Management).” The Wolfsberg Group (2020). https://db.wolfsberg-group.org/assets/a27f9bf6-b4a8-41d2-a390-6f1aaf797241/Wolfsberg%20SoW%20and%20SoF%20FAQs%20August%202020%20(FFP)_1.pdf.

27: FATF (2022), Guidance for a Risk-Based Approach to the Real Estate Sector, FATF, Paris, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/content/fatf-gafi/en/publications/Fatfrecommendations/Guidance-rba-real-estate-sector.html.

28: Ibid.

Published

July 05, 2023

Key Contacts

Key Contacts

Senior Managing Director

Managing Director

Director

Downloads

Most Popular Insights

- Beyond Cost Metrics: Recognizing the True Value of Nuclear Energy

- Finally, Pundits Are Talking About Rising Consumer Loan Delinquencies

- A New Era of Medicaid Reform

- Turning Vision and Strategy Into Action: The Role of Operating Model Design

- The Hidden Risk for Data Centers That No One is Talking About