Third Party Funding: A Source of Capital for Any Company With a Good Legal Claim

-

April 28, 2022

DownloadsDownload Article

-

Third party funding has become part of the construction claims conversation, from the site office to the head office. In this article, FTI Consulting and Augusta Ventures address some of the common questions and perceptions and clarify what is, in essence, a source of capital for any company with a good legal claim.

“If the claimant wins, the funder receives its money back plus a portion of the award. But if the claimant loses or cannot recover from the other side, then the funder does not recover its investment.”

“I’ve heard of third party funding but I don’t know how it works.”

Given the high volume of claims and disputes on construction projects, it is perhaps surprising that few in the industry know how to finance claims.

A third party funder provides finance by paying for a claimant’s costs of conducting a legal claim in return for a share of the award if the claim is successful. Funders generally pay for the budgeted fees of lawyers, counsel, independent experts and other disbursements. In appropriate cases, claims can also be monetised to finance other parts of the business such as working capital.

The unique feature of third party funding is that it is non-recourse finance. If the claimant wins, the funder receives its money back plus a portion of the award. But if the claimant loses or cannot recover from the other side, the funder does not recover its investment.

Funding can be used in any binding and enforceable claim forum — including adjudication, arbitration and litigation. It can also be sought at any stage in the dispute resolution process — from claim preparation through to hearing and even post-award if costly enforcement action is required.

Traditionally funders invested in single, standalone claims. Nowadays, however, it is equally possible to obtain finance for a portfolio of claims. A portfolio approach may be appropriate, for example, where a contractor’s expansion into a new territory has not gone well and the business is forced to pursue a number of costly contentious claims to revive problem projects, raising concerns about ‘throwing good money after bad’. By financing all of the claims under one facility, the funder reduces its risk because the proceeds from the wins will compensate for unrecovered investments in any losses. By reducing the overall risk, funding becomes cheaper and the contractor can finance a wider range of disputes.

“Third party funding is for the desperate and the insolvent. We can afford to pay our lawyers.”

Third party funding is now a common feature of the domestic and international dispute resolution process. It became part of the mainstream because, as practised by reputable funders, it is a force for good. However, perhaps most significantly, it is now perceived as a commercially prudent risk management tool for sophisticated businesses.

Construction contractors operate on some of the lowest profit margins in any industry — anecdotally even the biggest and the best accept margins of 2-5%. In that environment, any money spent on dispute lawyers is money that could have been invested in the company’s growth, for example, in new technology to improve efficiencies. Moreover, in seeking to manage that budget and cashflow tension, most construction businesses routinely forego revenue from good claims because the risk-reward analysis doesn’t justify the upfront cost of lawyers and consultants, and the attention of its commercial staff.

In this context, rather than being a last-ditch roll of the dice, funding can be of significant value to prudent, solvent construction businesses in two common scenarios.

- Where the alternative of self-funding the claim through its various stages would have such an impact on cash flow that the cost would inhibit the company’s ability to operate normally or profitably.

- Where self-funding will impede the company’s investment in its strategic and future needs such that the dispute will result in lost opportunities for the business, even if eventually won.

Whichever the scenario, the commercial reality is the same: a good claim is an unrealised asset of the company, and third party funding is a source of capital for any company with a good claim.

“Third party funding is hard to get and not worth the pain and effort.”

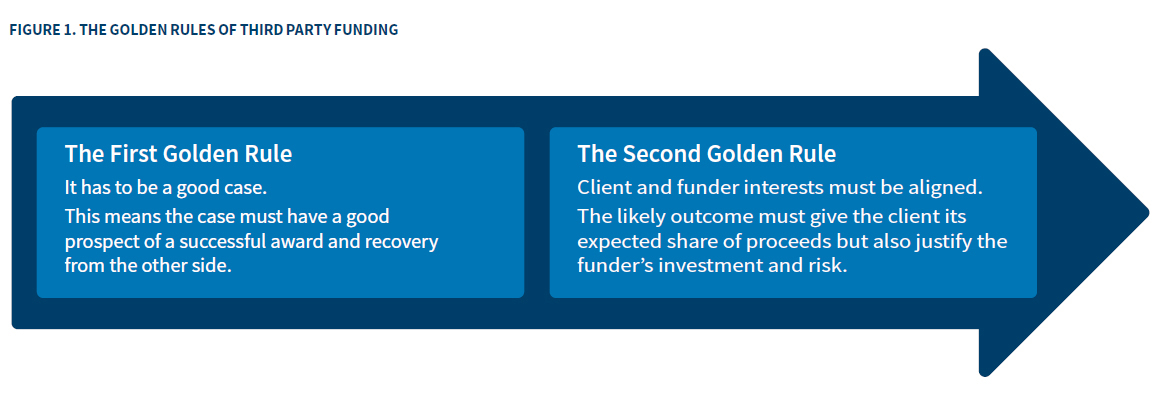

It is true that funding is not suitable for every construction claim. Considering the cost and risk associated with construction disputes, it is no surprise that funders are rigorous in their assessment of a case and can be quite selective. In simple terms, the two Golden Rules will determine whether a case is suitable for funding.

A funder’s business model requires it to win more cases than it loses. This is critical to minimise the cost of the funder’s capital and provide an equitable solution for claimants. As such, any case or portfolio a funder invests in must have at least a 60-65% chance of a successful outcome including recovery from the respondent.

Equally, a funder’s business model must be user-friendly. It must build a track record of delivering positive outcomes for claimants. This means ensuring that, whilst the funder will get a return that will justify its risk, the claimant can expect to get the bulk of the claim proceeds and be as satisfied with the outcome as if it had used its own money. To achieve that alignment of interests, a funder will carefully consider the budget-to-quantum (or ‘loan-to-value’) ratio.

If a case does not meet both the Golden Rules, a funder will say no.

“What would the funder need to see before deciding whether to fund?”

At the outset, funders do not require all the documents necessary to reach a decision nor do they require a case to be at a particular stage before they will consider funding. To initiate the funding process, a client or its representatives need only provide evidence that there are reasonable grounds to believe the Golden Rules can be satisfied. This will normally include:

- a written opinion from the lawyers on the prospects of the case;

- a preliminary analysis on quantum and, if applicable, delay or technical issues; and

- a budget for the legal costs and any other funding requirements.

If, based on this initial information, the funder considers that the Golden Rules can be satisfied, commercial terms will be offered. Subject to how well advanced the case is, the funder will usually need to ask for more information before a final decision can be made. But a well-established funder specialising in construction employs high quality construction law practitioners to ensure that it only asks for that which it needs.

“How long would it take to get funding? We need to press on with the claim.”

As with any due diligence process, a funder requires reasonable cooperation from the legal team and client. Throughout the process, however, a good funder will be acutely aware of time pressures and will know that it is essential to ask only for necessary information and reach a conclusion quickly.

A funder needs to give the right answer and not just a quick answer, but will respond as quickly as a proper assessment will permit. Depending on how quickly the claimant and its legal team want to move and are prepared to engage, many cases are capable of being funded in a matter of weeks. A typical adjudication claim could be diligenced in a matter of days. In other cases, the funding process is more of a journey and can require collaboration to develop the case and mitigate some of the risks.

“Why would we let someone else do our claims for us? It’ll cost us more in fees and there’s no guarantee they’ll get a better result for us — and take a huge cut of the money.”

A third party funder does not — and cannot — conduct or otherwise take control of the claim. Most jurisdictions have laws which prohibit a third party from controlling a legal claim. Indeed, that is one of the key reasons funders’ diligence must be rigorous: once they commit to funding a case, they cannot dictate the path it takes, who conducts it, or how it is run. They must therefore get comfortable with all aspects of the case — including the client’s chosen legal team — and predict as best they can the potential routes the claim may follow and obstacles it may encounter.

Once a funding agreement is in place, the funder will monitor the case like any other investment. This will include tracking, reviewing and reporting on budget spend (and, of course, paying the bills as they fall due) and receiving updates on case developments at regular intervals. When settlement opportunities arise, the funder will assist the client in understanding the potential commercial outcomes (including the distribution of proceeds) and it will be entitled to expect an offer to be accepted when the client’s legal team advises that it ought to be.

More generally, the funder is available as a critical friend that the client and legal team can turn to for an opinion at any stage during the legal process.

As to the cost and the funder’s success fee, it is a commercial choice for any construction business whether they wish to take the risk of a claim on their shoulders (the “downside risk”) and keep all of the potential upside to themselves, or whether they prefer to offload that downside risk to someone else and free up cashflow in return for sharing the upside. The focus of any reputable funder is to offer terms that make it attractive for claimants to choose the latter option.

Funders commonly structure their success fee based on a multiple of the funds the claimant has drawn down at the date of resolution or a percentage of the total recovery. Most importantly, the applicable multiple or percentage payable will depend on the length of time to resolution. To reflect the duration of the funder’s investment and incentivise settlement, the multiple is generally lower the earlier a claim is resolved or settled. Accordingly, if the claimant can achieve an early settlement, it will give up a much smaller cut of the proceeds to the funder.

Notably, in line with the trend towards widespread acceptance of third party funding as a positive influence on the dispute resolution process, tribunals and courts now consider claims for recovery of a funder’s success fee when awarding adverse costs against the losing party. In a recent example, a contractor succeeded in recovering US$1.7 million in third party funding fees after winning an arbitration.1 In dismissing the application to set aside the award, the English High Court confirmed that the arbitral tribunal was entitled to award funding costs.

Ultimately, whether to use funding is a matter of weighing up the alternatives and what works best for the business. In doing so, it can be helpful to compare not just the ultimate share of a successful outcome in the long term but also the impact self-funding may have on the business in the interim.

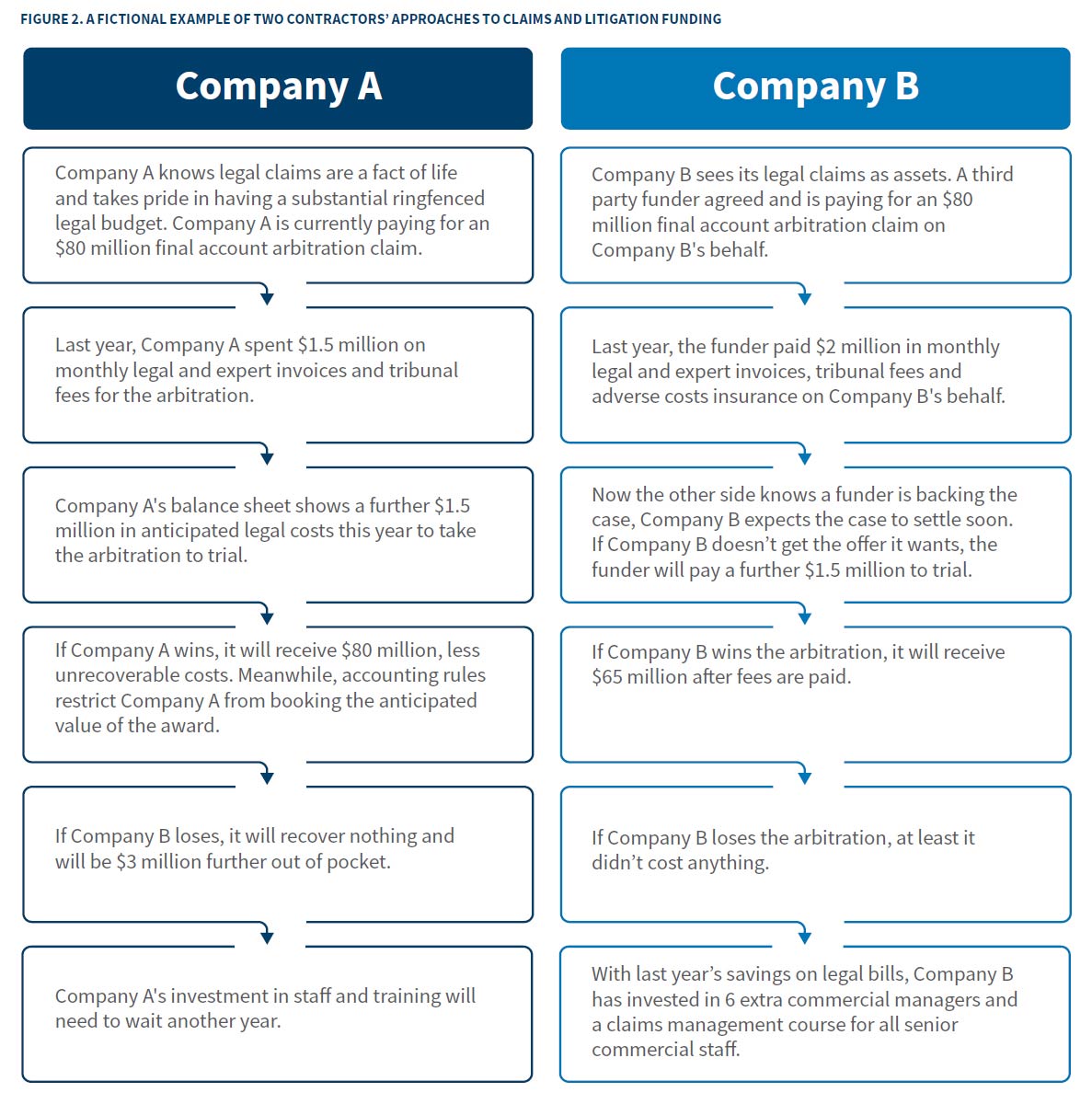

To illustrate, take the following comparison of two fictional contractors of a similar size, operating in the same market. Both are solvent and longstanding businesses. Both have fewer commercial managers than they would like on their larger projects. By no coincidence, they are both fighting several major disputes at any given time. However, both intend to invest in increasing and upskilling their commercial staff as soon as they have spare capital to invest.

The only real difference between Company A and Company B is that the former sees paying its own legal bills as a matter of commercial necessity and accepts the downside risk as part of the game. As third party funding continues to grow in mainstream dispute resolution, it can be expected that more contractors will adopt Company B’s business model.

Realising the benefits of third party funding

Third party funding is not for every business, nor every dispute, but the benefits are clear and you can be reasonably certain of the strength of your claim once a funder has diligenced it. For the right cases there are few drawbacks to third party funding. As awareness of its benefits increases, it may become mainstream in construction disputes.

This article was drafted in collaboration with Augusta Ventures. Authors from Augusta Ventures include:

Andrew Roberts

Head of Construction & Energy, Augusta Ventures

andrew.roberts@augustaventures.com

Published

April 28, 2022

Key Contacts

Key Contacts

Senior Consultant