- Accueil

- / Publications

- / Articles

- / Life After LIBOR: Interest on Damages

Life After LIBOR: Interest on Damages

-

décembre 05, 2024

TéléchargezDownload Article

-

Summary

Disputes can last for a number of years and as a result a claimant may receive damages a long time after suffering its loss. Claimants often claim interest as a result of this delay. It has been common for tribunals to award interest on damages at a rate based on the London Interbank Offered Rate (‘LIBOR’), often with some premium applied. However, since 30 September 2024, all LIBOR settings have ceased to be published. What other benchmark rates can tribunals rely upon and what might affect a tribunal’s choice between them?

- Despite there being potentially significant amounts at stake, interest and its purpose can often receive little discussion in the parties’ statements of case and in the tribunal’s award.

- Now LIBOR has been fully discontinued, it is not possible to calculate interest using LIBOR – what are the alternative approaches?

- LIBOR rates measured the cost of unsecured interbank borrowing for periods of up to one year, whereas other interbank borrowing benchmarks are mostly overnight rates – these therefore don’t provide like-for-like substitutes, particularly where LIBOR rates were used for borrowing terms of several months or more.

- With many alternative reference rates available, the appropriate benchmark will depend on the factual and legal circumstances of the case, as well as the purpose of an award of interest. This purpose could be compensation for: (i) the time value of money; (ii) the actual risks to which the claimant has been exposed; or (iii) the specific consequences for the claimant of being deprived of funds.

The Cost of Delays

It can take a long time to resolve a dispute. As a result, a claimant may receive damages many years after suffering its loss. Claimants often claim interest as a result of this delay, which can be a substantial amount – with compound interest having been described as ‘the most powerful force in the universe’ and the eighth wonder of the world.

This can be seen in the 2016 arbitration award in Crystallex v Venezuela, where the tribunal awarded interest at a rate of USD 6-month LIBOR + 1%, compounded annually on damages of $1.2 billion, with interest accruing from April 20081 – which we estimate at $600 million by September 2024.

The right approach to an award of interest may depend on matters of fact, law and economics. However, despite there being potentially significant amounts at stake, interest can often receive relatively little discussion in the parties’ statements of case and in the tribunal’s award.

It has been quite common for tribunals to award interest at a rate based on LIBOR, often with some premium applied – with interest being based on LIBOR seen in approximately one-third of publicly available ICSID awards. However, LIBOR has been discontinued since September 2024, meaning parties, experts and tribunals are no longer able to rely on it as a reference rate. Given this new era of life after LIBOR, what is the purpose of an award of interest on damages? How best can those purposes be achieved? What options are available?

LIBOR in Interest Awards

Introduction to LIBOR

From the 1970s until the early 2020s, LIBOR was a widely used reference rate for various financial transactions, including loans and derivatives. It was intended to represent the interest rate at which large international banks could borrow funds from one another in the wholesale interbank funding market in London.

Historically, LIBOR was published across five currencies (USD, EUR, GBP, JPY and CHF) and seven maturities (overnight, one week, one month, two month, three month, six month and one year) for a total of 35 LIBOR ‘settings’.

The Use of LIBOR in Interest Awards

LIBOR has historically been a popular reference rate for calculating pre-award interest, and some investment treaties have even required interest to be calculated based on LIBOR.2 Awards of the form ‘LIBOR + X%’ have been common, with a 2% premium particularly widely used. A premium to LIBOR is generally considered to reflect the difference between the cost of borrowing of banks and other types of businesses. For example, in Lemire v Ukraine, the tribunal awarded interest at LIBOR + 2%, finding that “LIBOR reflects the interest at which banks lend to each other money. Loans to customers invariably include a surcharge, and this surcharge must be inserted in the calculation of interest.”3

The common use of LIBOR + X% gave lawyers, experts and tribunals an easy reference point when assessing interest. In Houben v Burundi, the tribunal explained its interest award simply by stating “the LIBOR rate in US dollars at 6 months + 2% constitutes a reasonable rate frequently applied by arbitration tribunals ruling on investment matters.”4

The Discontinuation of LIBOR

As has been well documented, investigations by various central banks, regulators and prosecutors in multiple countries have found that certain banks manipulated LIBOR, resulting in substantial fines. This contributed to the UK Financial Conduct Authority, the regulator of LIBOR, announcing that LIBOR would start to be discontinued from the end of 2021.5 The last LIBOR settings were published at the end of September 2024, with market participants having already been encouraged to switch to alternative interest rate benchmarks ahead of the discontinuation.

Alternative Interest Rate Benchmarks

With this change, regulators have identified alternative benchmark rates including the Secured Overnight Financing Rate Data (‘SOFR’) as an alternative for USD LIBOR, the Sterling Overnight Index Average (‘SONIA’) as an alternative for GBP LIBOR, and the Euro Short Term Rate (‘€STR’) as an alternative for EUR LIBOR. Regulators have worked closely with market participants, including banks, asset managers, pension funds and insurance companies, to lead a transition to these alternative interest rate benchmarks in bond, loan and derivative markets.6

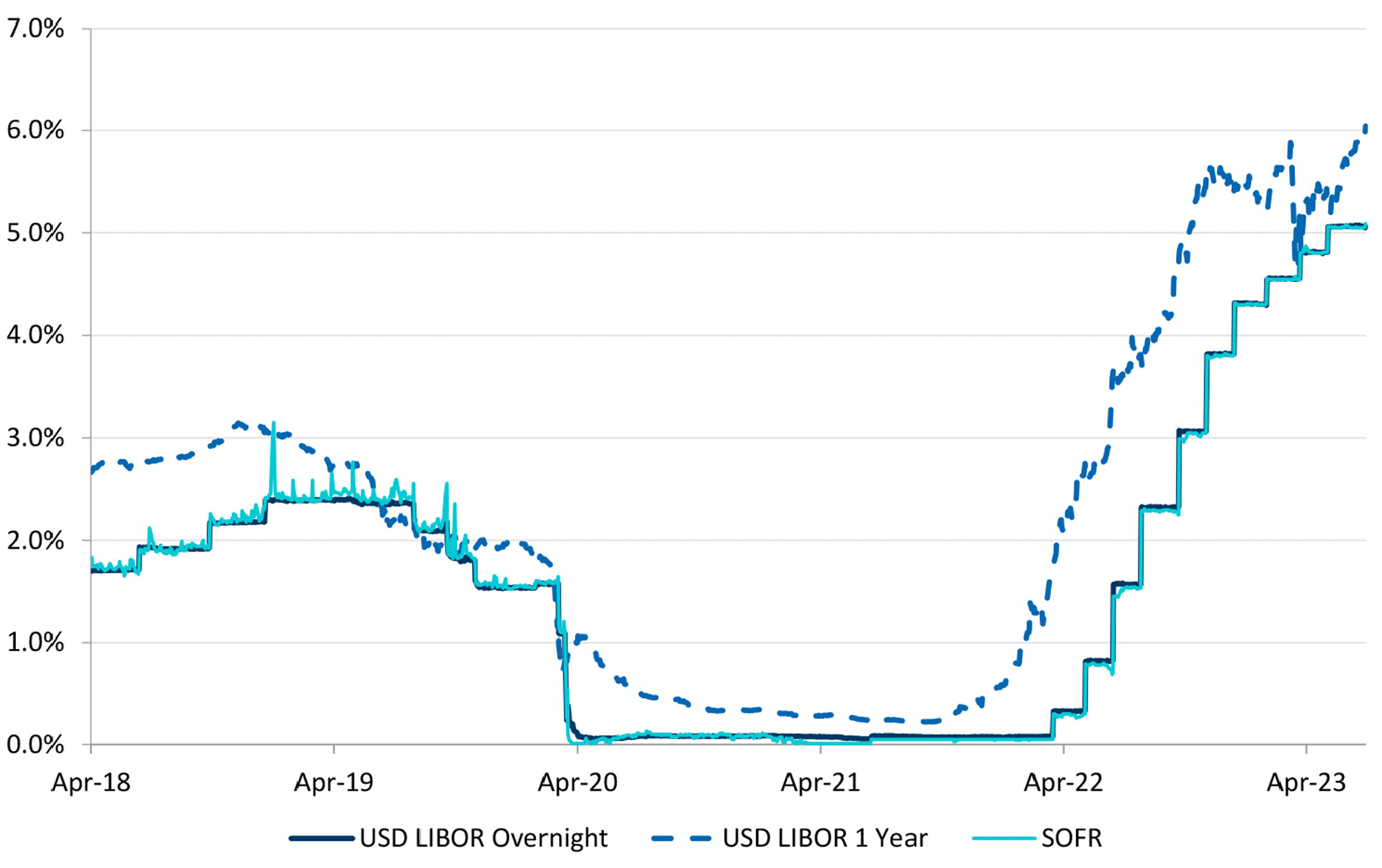

The alternative benchmark rates do not provide a like-for-like replacement for LIBOR. Similarly to LIBOR, they are interbank lending rates, but are overnight rates whereas LIBOR was available for maturities of up to one year. As shown in the figure below, historically SOFR provides a reasonable approximation to overnight USD LIBOR but differs significantly when compared to longer-term USD LIBORs, such as the one-year rate.

SOFR and overnight and one-year USD LIBOR, April 2018 to June 2023

Note: Overnight USD LIBOR was discontinued in June 2023.

Source: Capital IQ and Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

It is in principle possible to adjust SOFR, or other replacement benchmarks, for certain differences to LIBOR. For example, the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (‘ISDA’) has published spread adjustments which can be added to SOFR to address differences between SOFR and LIBOR, including a term premium. These methodologies have generally been published to provide a solution to ‘tough legacy contracts’, which cannot adequately be transitioned away from LIBOR.7

Implications for Interest Awards

With the discontinuation of LIBOR an alternative approach to calculating interest is needed – many tribunals started to use alternative methods sooner than the deadline. For example, in 2019, the tribunal in Magyar Farming v Hungary awarded interest based on EURIBOR (which reflects the borrowing rates for banks in the Eurozone) rather than EUR LIBOR (which reflected the euro-denominated borrowing rates for banks in London) – a small but nuanced difference. The tribunal adopted this rate primarily due to LIBOR being phased out and calculations no longer being possible in the future, while EURIBOR had been reformed and will continue to be published.8

More recently, tribunals in a number of investor-state disputes have considered what alternative rates might be adopted, and reached a variety of different conclusions. For example, the tribunal in MOL v Croatia determined that once LIBOR was no longer published, the alternative rate should be “whatever rate is generally considered equivalent to LIBOR in respect of sums due in US dollars”, while the tribunal in JSC Tashkent v Kyrgyzstan determined that the alternative rate should be the 10‑year United States Treasury rate.9

For amounts expressed in euros, EURIBOR may provide a suitable substitute for EUR-denominated LIBOR, as was determined by the tribunal in Magyar Farming v Hungary. However, similar rates are not available for all the LIBOR currencies, so the interbank rates discussed above provide a potential alternative.

Awards based on LIBOR have typically referenced six-month or one-year LIBOR rates, with very few if any awards referencing overnight LIBOR. Following the discontinuation of LIBOR, it is very unlikely to be appropriate to simply switch from a ‘USD LIBOR + 2%’ approach to a ‘SOFR + 2%’ approach, if the objective is to approximate a rate with a maturity longer than overnight, given the major differences between overnight and longer-term rates as shown in the figure below.

There are methodologies published to allow for the adjustment of these alternative benchmark rates to be consistent with LIBOR, such as the ISDA spread adjustment to SOFR described above. In a separate context to an assessment of interest on damages, a UK High Court recently held that this rate (i.e., SOFR plus the ISDA spread adjustment) was a ‘reasonable alternative’ contractual interest rate to apply to a series of LIBOR-linked financial instruments, following the discontinuation of USD LIBOR.10

In addition, there are other reference rates available, including risk-free rates and measures of the borrowing costs of borrowers of various credit qualities which could provide relevant reference points for calculations of interest.

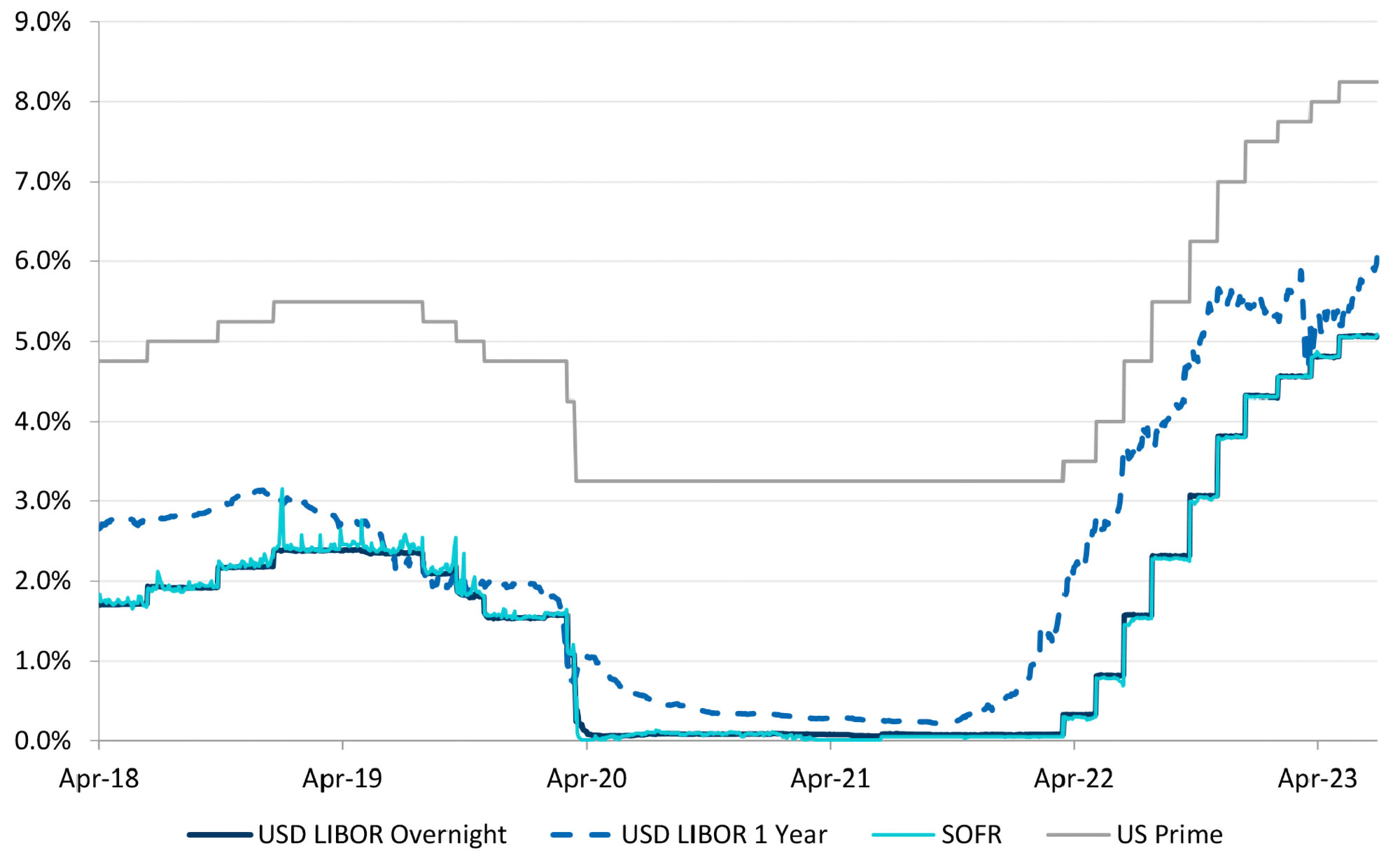

In the case of USD borrowings, one such reference point is a rate known as US Prime – the rate at which large US banks lend money to their most creditworthy corporate customers. However, this rate is quite different to interbank lending rates such as LIBOR or SOFR. As shown in the figure below, US Prime has been approximately three percentage points higher than overnight LIBOR.

US Prime, SOFR and overnight and one-year USD LIBOR, April 2018 to June 2023

Note: Overnight USD LIBOR was discontinued in June 2023.

Source: Capital IQ; Federal Reserve Bank of New York; and Federal Reserve Economic Data.

Despite this difference, in a UK High Court context it was held that going forward the “default” pre-judgment interest rate for US dollar awards in the Commercial Court will be US Prime, possibly plus a premium of 1% or 2%.11

Ultimately from an economic perspective, the appropriate replacement reference rate for interest will depend on the purpose of interest. So, how should the choice of interest awards be approached in practice?

The Choice of Interest Rate for Interest Awards

What Interest Rates are Awarded in Practice?

The precise rate that may be awarded depends on the context and nature of the claim. In some cases, the approach to interest may be governed entirely by the applicable law, such as where statutory rates apply. That said, courts still have broad discretionary powers to award interest.

In our experience as valuation experts, there is greater discretion – and variety – in the rates awarded in international arbitration and there is no single approach that can be used to assess interest in all situations. As one practitioner explains:

International investment treaties often specify that interest should be awarded at a “normal commercial rate”, “appropriate market rate”, “commercially reasonable rate” or similar.13 However, a wide range of rates fit these descriptions. For instance, in 2020 the UK government issued certain bonds with a negative yield, while at a similar time Ford issued bonds with a yield of 8.5%. Both rates could be considered ‘commercial’ rates at the time, in that they reflected the views of investors in the bond market.

Given the lack of an established approach for calculating interest and the limited guidance within some international investment treaties, a wide variety of rates are seen in practice, including:

- Statutory or contractual rates: In some circumstances, the applicable law or contract may identify the interest rate to be applied.14

- ‘Fair’ or ‘reasonable’ rates: Some awards refer to a “fair” or “reasonable” rate, often set at the discretion of the tribunal with limited explanation.15 Without further information, it is not always possible to say what factors a tribunal has considered in reaching its conclusion.

- ‘Coerced loan’ approach: This considers the respondent’s cost of borrowing, on the basis that the claimant has effectively lent money to the respondent for the period between the date when damages are assessed and when they are paid.16

- Claimant’s ‘borrowing rate’: Awards of interest at the claimant’s borrowing rate are sometimes justified on the basis that the claimant has, or may have had, higher borrowings as a result of not having access to the money claimed.17 This approach may be implemented using reference rates such as LIBOR plus a premium, which is often considered to reflect the cost of borrowing for large non-financial corporations.

- Returns on alternative investments: Some claimants claim for interest based on the returns that they could, or would, have earned if they had been able to invest the amount claimed. This approach often considers the returns on low-risk investments, such as government bonds or United States certificates of deposit,18 but can also consider riskier investments such as an investment in a specific project.19 Some claimants claim for their weighted-average cost of capital (‘WACC’), on the basis that this is the return that they would have sought on any funds available to them.20

What is the Purpose of Interest?

The appropriate interest rate will depend on the purpose of the award of interest, with at least three purposes sometimes discussed that are not necessarily mutually exclusive:

- Compensation for the loss of use of money: The most common rationale given for awarding interest is to compensate the claimant for the loss of use of money resulting from the breach. For instance, in Vivendi v Argentina (I) the tribunal considered that:

- Restitution for unjust enrichment of the respondent: Interest may be awarded to ensure the respondent has not profited as a result of compensation being delayed. In the Sempra Metals litigation, Lord Nicholls stated that:

- Promotion of efficiency: A third reason for awarding interest is to encourage timely settlement of disputes by discouraging the respondent from seeking to delay resolution.23 This purpose reflects the possibility that, if interest were not awarded (or if the rate awarded were too low), the respondent might lack an incentive to resolve the dispute in a timely manner.

In our experience, interest as compensation is the purpose most often referred to by tribunals when making an award of interest, although tribunals adopt various interest rates to achieve this purpose. Interest as restitution is also referred to by tribunals, although less frequently in our experience, and some tribunals specifically reject calculations of interest on this basis.24 In contrast, we are not aware of any awards which have assessed an appropriate interest rate based solely on achieving an objective of efficiency.

What Interest Rates Should be Awarded?

From an economic perspective, if the primary purpose of interest is to compensate for the loss of use of money, this can cover a broad range of consequences. We set out below a potential economic framework for determining the appropriate interest rate, distinguishing between three approaches:

- Compensation that accounts only for the time value of money.

- Compensation that reflects the risks to which the claimant has been exposed as a result of being owed money by the respondent.

- Compensation for the specific consequences of the claimant not having access to the money claimed, which will depend on how the claimant would have used the money – such as to repay borrowings and avoid interest, or to fund an investment.

Which of these three approaches is appropriate is often primarily a matter of law.

Compensation for the Time Value of Money

Under this approach, the claimant should be compensated for the ‘time value of money’ – that it is preferable to receive a certain amount of money today rather than in the future. This requires the claimant to be awarded interest of at least the risk-free rate, where there is no or negligible chance of default by the borrower. In this context, widely used risk-free rates include the yields on bonds issued by the governments of large stable economies, such as the United States (for an award in USD) or Germany (for an award in EUR).

One practical issue that may arise when awarding interest at the risk-free rate is that, in some currencies, the yield on instruments typically used to measure the risk-free rate has at times been negative. As an example, yields on 10-year Danish government bonds denominated in kroner were negative from around early 2019 to late 2021. Tribunals may be uncomfortable awarding negative interest.

Compensation for the Risks to Which the Claimant has Been Exposed

An award of interest at the risk-free rate assumes that the claimant should not be compensated for any investment risks. However, it may be appropriate to award interest at a higher rate, if the claimant is entitled to compensation for certain risks.

Claimants face the risk that the respondent will default on its obligations under any award of damages, for instance because it does not have enough funds to cover the award. Interest at the risk-free rate is generally insufficient to compensate for this default risk. This can be seen from the fact that most respondents can only borrow at rates higher than the risk-free rate, given their perceived creditworthiness. The tribunal in ConocoPhilips v Venezuela explained that an award of interest at the risk-free rate would “make it substantially attractive for [the respondent] to borrow money from the investor at such rate.”25

Accordingly, some claimants claim interest at the respondent’s cost of borrowing, which reflects the respondent’s default risk. This approach is sometimes expressed as saying that the claimant has essentially been forced to make a loan to the respondent, and bears the respondent’s credit risk between the date of breach and the date of award, and thereafter if the respondent does not pay the award immediately. This situation is sometimes referred to as a ‘coerced loan’, made by the claimant to the respondent.

Tribunals have explicitly adopted the coerced loan approach in a relatively small number of publicly available awards. Examples include Cargill v Mexico, where the tribunal considered that the claimant has “effectively loaned this sum to respondent for the duration of this dispute”,26 and Bear Creek v Peru, where the tribunal adopted an interest rate consistent with “Peru’s external cost of debt financing from private lenders.”27

One argument sometimes levied against the coerced loan approach is that, in situations where the respondent pays the award, it is known not to have defaulted and hence it would not be appropriate to compensate the claimant for a risk that has not come to pass. This is consistent with our experience that awards of interest tend to be assessed on an ex post basis, taking account of all information available at the current date, including actual interest rates, rather than restricting analysis to the information set available at the date of the breach. However, the premise of the coerced loan approach is that the claimant has still borne the risk, even if it has not materialised. Further, an award of interest at the respondent’s cost of borrowing achieves another potential purpose of an award of interest – it avoids the respondent profiting as a result of compensation being delayed.

Compensation for the Specific Consequences of the Delay in Compensation

When applying either of the two approaches above, it is not necessary to consider the characteristics of the claimant. An alternative approach is to consider how the claimant would have used the relevant funds – they may have used these funds to:

- Invest in low-risk assets to earn interest.

- Repay debt or avoid taking on new debt, thereby reducing its interest expenses.

- Invest in its own business or other projects.

- Pay dividends to shareholders or avoid raising additional equity finance.

Some commentators refer to a claim that addresses the specific way in which the claimant would have used the funds as being for ‘interest as damages’, rather than ‘interest on damages’, as this assessment is often performed by comparing the claimant’s position in the actual and counterfactual positions since the date of harm.

Under English law, parties sometimes refer to the Sempra Metals litigation when discussing the award of interest as damages. In this case, Lord Nicholls stated that:

And Lord Scott stated that:

This decision specifically considered claims for compound interest. However, the decision indicates that more general claims for interest as damages can be made if the claimant can prove its actual losses. In other words, claims for interest are subject to “remoteness, mitigation and all the other general rules on damages.”30

The evidence required to prove the consequences of the delay in compensation may depend on the situation. For instance, a company with significant short- and long-term debt and a sophisticated treasury management function may not require much evidence to persuade a tribunal that it could have used additional funds to reduce its existing debt. Potentially because of this, some tribunals may award interest based on the claimant’s cost of borrowing in the absence of any detailed discussion of how the claimant would have used the funds.31

In comparison, a claimant may require much more evidence to persuade a tribunal that it would have invested additional funds in a project which it considers would have been highly profitable. Such a claimant may need to show why it could not fund the project in another way and how it can assess how profitable the project would have been.

Claims for Interest Based on the Claimant’s WACC

One particular application of the ‘specific consequences’ approach is to award interest at the claimant’s WACC, which reflects the average cost of the sources of capital, namely debt and equity, used to finance a business. The WACC will often be a higher interest rate than those other rates discussed above.

It is rare, in our experience, for tribunals to award interest at the claimant’s WACC. One tribunal that did so was Vantage v Petrobras.32 A claim for interest at the WACC is – at least implicitly – a claim that the claimant could have reinvested the funds in its own business and expected to earn a return at least equal to its cost of capital. Those expected returns reflect the risk of investing in the claimant’s business.

Before awarding interest at the claimant’s WACC, the tribunal should be mindful that the claimant did not have access to the money and so did not in fact invest it, and hence was not exposed to the risks associated with the relevant investment. In GAI and Rurelec v Bolivia, the tribunal rejected the claimant’s claim for interest at the WACC, stating that:

One potential counterargument to this position is that the claimant has not borne these risks because it has been denied the opportunity to do so. However, if the claimant has been denied investment opportunities, it would be open to them to quantify their resulting losses in the usual way. This might require it to:

- Identify the specific opportunities foregone.

- Demonstrate that it would otherwise have pursued these opportunities.

- Explain why it could not borrow money to pursue these opportunities.

- Explain whether its ability to pursue these opportunities has been lost entirely or simply delayed.

- Show what cash flows have been lost as a result, which may differ to a return at the rate of the WACC.

The nature of such investigations is consistent with the extent of analysis and evidence that is often provided in support of the core damages to which interest is to be applied.

Interest on Damages in Times of High Inflation

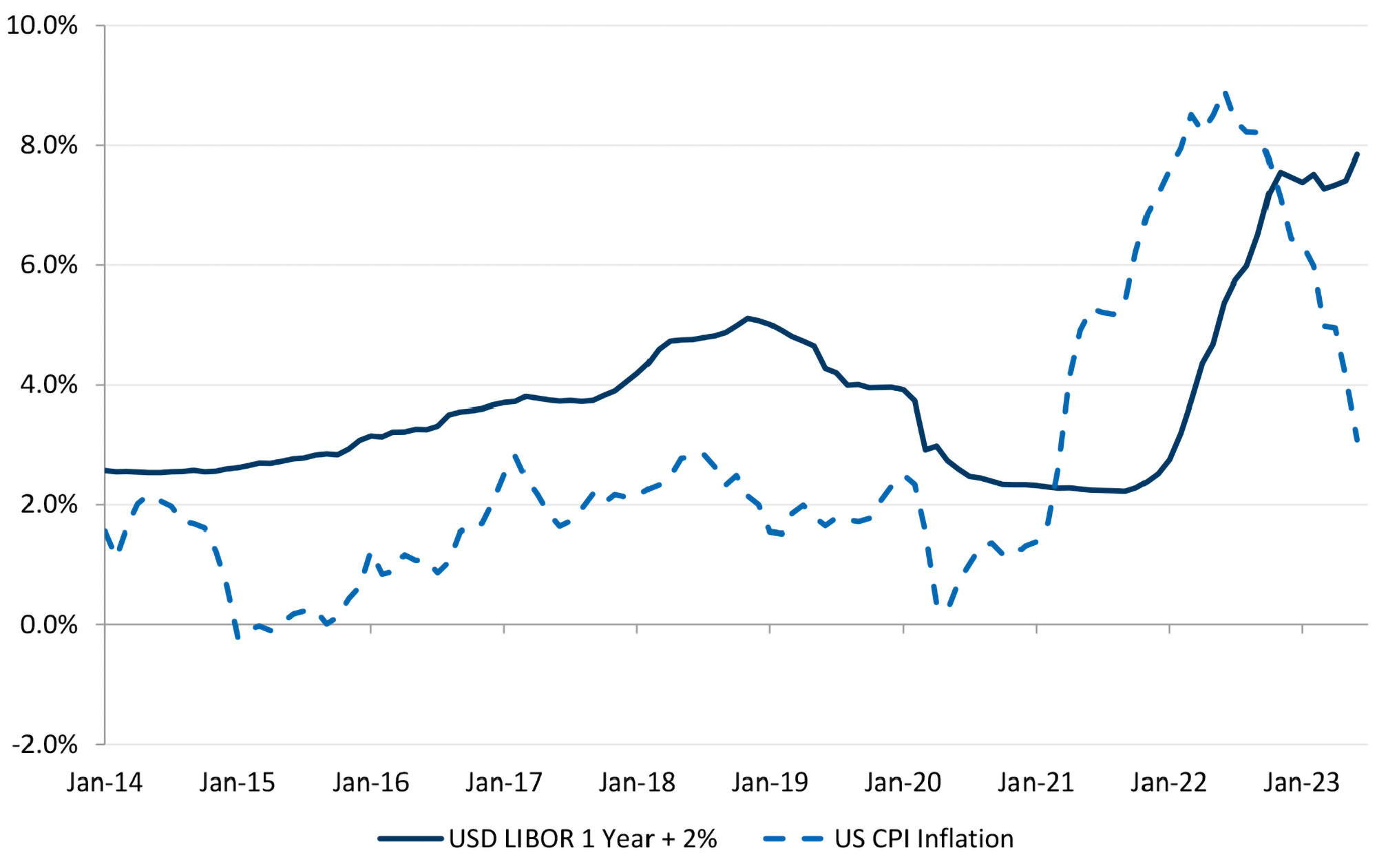

In recent years, the global economy has been through a period of high inflation. The figure below shows how US inflation compares to USD LIBOR + 2% through to June 2023, when USD one-year LIBOR was discontinued.

US CPI inflation and one-year USD LIBOR + 2%, January 2014 to June 2023

Note: One-year USD LIBOR was discontinued in June 2023.

Source: Capital IQ; and Federal Reserve Economic Data.

It can be seen that in the past, an award in the form of ‘LIBOR + 2%’ could be expected to more than compensate for inflation but more recently would not wholly compensate the claimant in some periods. Our experience is that some claimants have considered arguing that interest awards should be set at such a rate that they are at least compensated for high inflation.

From an economic perspective, it does not necessarily follow that interest should be awarded at a rate that exceeds the rate of inflation. Our economic framework identifies three potential bases for awarding interest – none of which necessarily means that the interest rate should be expected to keep pace with inflation, although the application of this framework will depend on the factual and legal aspects of the case:

- If interest is intended to compensate for the time value of money, then the interest rate should be set by reference to the risk-free rate. This has not kept pace with inflation in recent years.

- If interest is intended to compensate for the risks to which the claimant has been exposed as a result of being owed money by the respondent, then the interest rate should depend on the respondent’s borrowing rate. This will not necessarily increase to the same extent as inflation rates.

- If interest is intended to compensate for the specific consequences of the claimant not having access to the funds, then the rate should reflect the benefit that the claimant would have received had it been able to use the funds. This will not necessarily compensate for inflation. This can easily be seen in practice by reference to savings rates, which have not increased to the same extent as inflation rates.

In other words, there is no reason that interest rates should – from an economic perspective – be expected to automatically compensate for inflation. If interest rates for awards are set by reference to inflation, then that is equivalent to setting an interest rate such that it preserves the purchasing power of the award. In our experience, it is uncommon for awards of interest to be set with this intention.

Final Thoughts

A wide variety of interest rates are awarded in practice. Tribunals often provide limited explanation of their choice of rate, despite there potentially being a significant amount of money at stake. In publicly available awards, around one-third of ICSID tribunals used LIBOR as a reference rate, often adding a premium to this rate. However, the discontinuation of LIBOR means that such approaches are no longer available to parties, experts and tribunals, although other reference rates are available. To date, ICSID tribunals appear to have reached different conclusions as to what the appropriate alternative reference rate might be.

When identifying an appropriate interest rate, parties and tribunals may distinguish between three approaches to an award of interest: (i) compensation for the time value of money; (ii) compensation for the actual risks to which the claimant has been exposed; and (iii) compensation for the specific consequences for the claimant of being deprived of funds. The appropriate approach must reflect the factual and legal circumstances of the case.

The relevant reference rate will depend on which of these approaches is chosen:

- The yields on bonds issued by the governments of large stable economies are often used to estimate risk-free rates which will compensate claimants for the time value of money.

- The cost of borrowing of a respondent can be estimated from its actual borrowing costs or a review of its creditworthiness – which will potentially be readily assessed if the respondent has a credit rating – and the cost of borrowing of other borrowers of a similar credit quality.

- An award based on the specific consequences for the claimant will depend on its specific circumstances – an award of interest at the WACC will not necessarily reflect those circumstances. Instead, the consequences of a delay in compensation may best be assessed by reference to the interest that the claimant could have earned on bank deposits, the interest that the claimant could have saved from borrowing less money, the return that the claimant would have earned on a specific opportunity that the claimant was prevented from pursuing, or some other rate.

If tribunals wish to continue to rely on bank borrowing rates as a benchmark for awards of interest, then they may pick an alternative ‘IBOR’ which is still published, such as EURIBOR as a substitute for EUR-denominated LIBOR, or use an overnight bank borrowing rate such as SONIA, adjusted as appropriate to reflect the desired maturity. It may also be appropriate to add a premium to the chosen rate to reflect the relevant level of credit risk, whether 2% or otherwise.

Ultimately there are many options available in regards to calculating interest on damage awards. With LIBOR having been discontinued, it remains to be seen whether other rates will become as ubiquitous as LIBOR once was.

The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and not necessarily the views of FTI Consulting, Inc., its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, or its other professionals. FTI Consulting, Inc., including its subsidiaries and affiliates, is a consulting firm and is not a certified public accounting firm or a law firm.

Footnotes:

1: See Crystallex International Corporation v Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, ICSID Case No. ARB(AF)/11/2, Award dated 4 April 2016, paragraph 961.

2: For example, see Waguih Elie George Siag and Clorinda Vecchi v The Arab Republic of Egypt, ICSID Case No. ARB/05/15, Award dated 1 June 2009, paragraph 597.

3: See Joseph Charles Lemire v Ukraine, ICSID Case No. ARB/06/18, Award dated 28 March 2011, paragraph 355.

4: Translated from the original French. See Joseph Houben v Republic of Burundi, ICSID Case No. ARB/13/7, Award dated 12 January 2016, paragraph 258.

5: See for example Financial Conduct Authority, ‘Announcements on the end of LIBOR’.

6: See for example Financial Conduct Authority, ‘Transition from LIBOR’.

7: See Regulation 88 FR 5204.

8: See Inicia Zrt, Kintyre Kft and Magyar Farming Company Ltdv Hungary, ICSID Case No. ARB/17/27, Award dated 13 November 2019, paragraph 432.

9: See MOL Hungarian Oil and Gas Company Plc v Republic of Croatia (I), ICSID Case No. ARB/13/32, Award dated 5 July 2022, paragraph 708(11); and JSC Tashkent v Kyrgyzstan, ICSID Case No. ARB(AF)/16/4, Award dated 17 May 2023, paragraph 786.

10: Standard Chartered plc v Guaranty Nominees Limited & Ors [2024] EWHC 2605 (Comm) (15 October 2024).

11: Lonestar Communications Corporation LLC v Kaye & Ors [2023] EWHC 732 (Comm) (30 March 2023).

12: Matthew Secomb, ‘Interest in International Arbitration’, Oxford International Arbitration Series, 2019, paragraph 1.02.

13: Quotations in the text are from the United Kingdom 2008 model BIT, France 2006 model BIT and Canada 2004 model BIT, respectively.

14: For example, see Swisslion DOO Skopje v Macedonia, former Yugoslav Republic of, ICSID Case No. ARB/09/16, Award dated 6 July 2012, paragraph 358.

15: For example, see Impregilo S.p.A. v Argentine Republic, ICSID Case No. ARB/07/17, Award dated 21 June 2011, paragraph 383.

16: For example, see Cargill, Incorporated v United Mexican States, ICSID Case No. ARB(AF)/05/2, Award dated 18 September 2009.

17: For example, see Tidewater Investment SRL and Tidewater Caribe, C.A. v Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, ICSID Case No. ARB/10/5, Award dated 13 March 2015.

18: For example, see Siemens A.G. v The Argentine Republic, ICSID Case No. ARB/02/8, Award dated 17 January 2007, paragraph 396.

19: For example, see Alpha Projektholding GmbH v Ukraine, ICSID Case No. ARB/07/16, Award dated 8 November 2010, paragraph 514.

20: For example, see Vantage Deepwater Company and Vantage Deepwater Drilling, Inc. v Petrobras America Inc., Petrobras Venezuela Investments & Services, BV and Petróleo Brasileiro S.A. (Petrobras Brazil), ICDR Case No. 01-15-0004-8503, Final Award dated 29 June 2018.

21: See Compañía de Aguas del Aconquija S.A. and Vivendi Universal S.A. v Argentine Republic, ICSID Case No. ARB/97/3, Award dated 20 August 2007, paragraph 9.2.3.

22: See Sempra Metals Limited v Her Majesty's Commissioners of Inland Revenue & Anor. [2007] UKHL 34.

23: For example, see Thierry J. Sénéchal & John Gotanda, ‘Interest As Damages’, Columbia Journal of Transnational Law, 2009, page 496.

24: For example, see Tidewater Investment SRL and Tidewater Caribe, C.A. v Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, ICSID Case No. ARB/10/5, Award dated 13 March 2015, paragraph 205.

25: See ConocoPhillips Petrozuata B.V., ConocoPhillips Hamaca B.V. and ConocoPhillips Gulf of Paria B.V. v Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, ICSID Case No. ARB/07/30, Award dated 8 March 2019, paragraphs 813 to 815.

26: See Cargill, Incorporated v United Mexican States, ICSID Case No. ARB(AF)/05/2, Award dated 18 September 2009, paragraph 544.

27: See Bear Creek Mining Corporation v Republic of Peru, ICSID Case No. ARB/14/21, Award dated 30 November 2017, paragraphs 713 and 714.

28: See Sempra Metals Limited v Her Majesty's Commissioners of Inland Revenue & Anor. [2007] UKHL 34.

29: Ibid.

30: Harvey McGregor, ‘McGregor on Damages’, 18th Edition, paragraph 15-072.

31: For example, see Tidewater Investment SRL and Tidewater Caribe, C.A. v Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, ICSID Case No. ARB/10/5, Award dated 13 March 2015, paragraph 205.

32: See Vantage Deepwater Company and Vantage Deepwater Drilling, Inc. v Petrobras America Inc., Petrobras Venezuela Investments & Services, BV and Petróleo Brasileiro S.A. (Petrobras Brazil), ICDR Case No. 01-15-0004-8503, Final Award dated 29 June 2018, paragraph 457D.

33: See Guaracachi America, Inc. and Rurelec PLC v The Plurinational State of Bolivia, UNCITRAL, PCA Case No. 2011-17, Award dated 31 January 2014, paragraph 615.

Date

décembre 05, 2024

Téléchargez

Most Popular Insights

- Beyond Cost Metrics: Recognizing the True Value of Nuclear Energy

- Finally, Pundits Are Talking About Rising Consumer Loan Delinquencies

- A New Era of Medicaid Reform

- Turning Vision and Strategy Into Action: The Role of Operating Model Design

- The Hidden Risk for Data Centers That No One is Talking About