Buy or Rent? Why the Australian Dream Might Be Due for a Makeover

The Economics of Housing Insight Series

-

September 15, 2025

-

The belief that “rent is dead money and buying is the pathway to prosperity” is widely held in the Australian housing market. But amid a housing crisis, homeownership is out of reach for many Australians, leaving them excluded from the capital gains typically associated with property ownership. So, is buying a home the only way to build wealth? Should homeownership be a goal for most Australians? This article analyses the long-term financial implications of various housing choices and assesses potential policy interventions to address the challenges.

Rethinking the Rent vs Buying Debate in Australia’s Changing Housing Market

For many households, the decision to rent or buy is a complex trade-off between lifestyle, stability, risk tolerance and long-term investment. A home is both a place to live and a major financial asset, but purchasing a property requires upfront capital, continued ongoing expenses and exposure to market risk. Conversely, renting offers flexibility and liquidity, potentially freeing up resources to be invested elsewhere. This, however, comes at the cost of the stability and security that homeownership can provide.

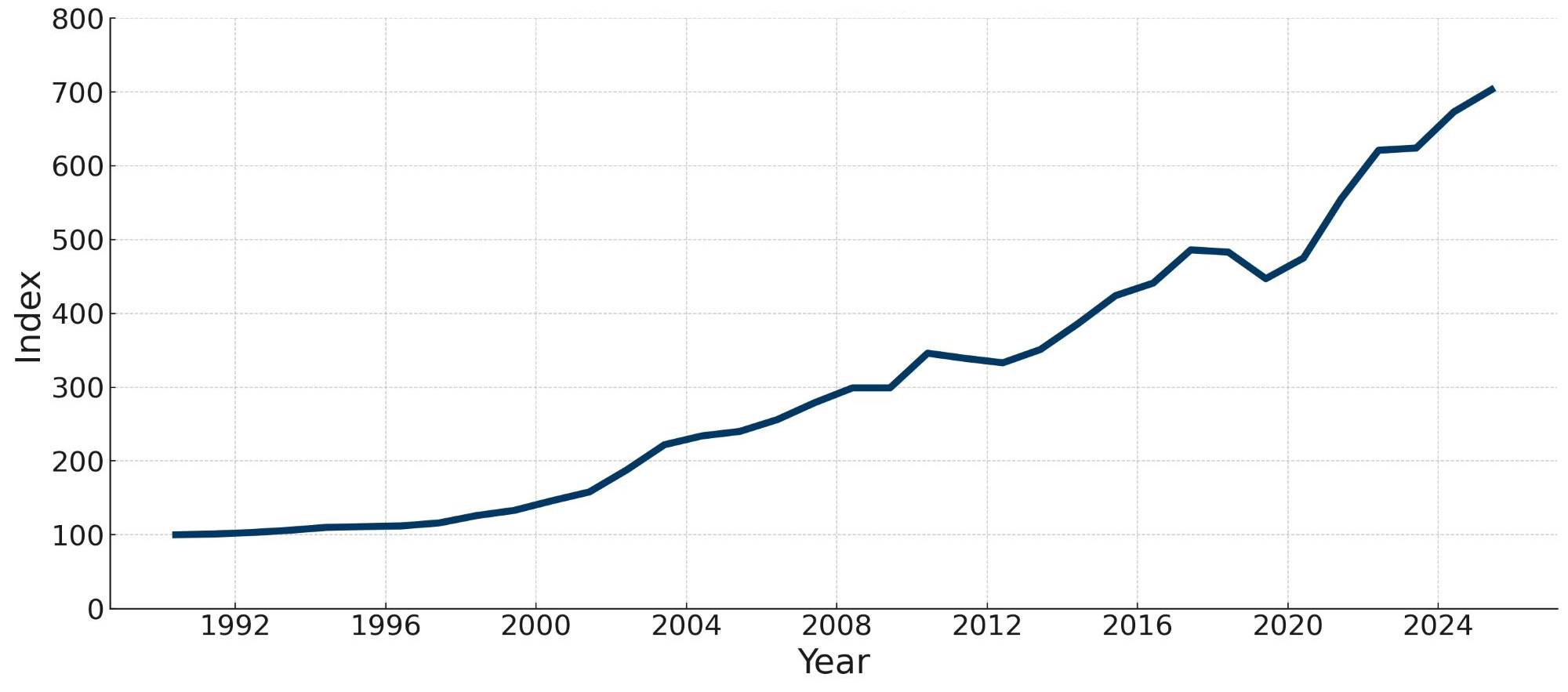

Residential property in Australia has historically been regarded as a reliable vehicle for long-term wealth creation. Across Australia’s eight capital cities, house prices have increased sevenfold since 1990.

Figure 1 - Average House Price Index - 8 Capital Cities (Base year: 1990 = 100)

Source: FTI Consulting analysis of ABS data

Recent surges in house prices have dealt a double blow to prospective first home buyers. Not only have they missed out on recent capital gains, but homeownership now feels even further out of reach. As a result, a growing share of Australians, particularly younger people, are renting. In 1975, around 45% of 30-year-olds were tenants.1 Today, that figure has climbed to nearly 65%. This shift reflects broader changes in affordability, lifestyle preferences and investment alternatives.

These trends contrast with a commonly held view that homeownership is essential for a secure retirement.2 In response, successive state and federal governments have introduced a range of grants and concessions aimed at helping first home buyers enter the market. These include stamp duty concessions, grants, access to super savings and government guarantees for borrowing up to 95% of the value of a first home.

But in an era where renting is becoming more common, particularly among younger generations, an important question arises: does renting necessarily mean giving up the opportunity to build long-term financial security?

Housing Affordability in Australia Through a Generation

Persistent growth in house prices over time may reinforce the perception that prices rise uncontrollably. However, house prices are influenced by multiple factors, with household income growth and interest rates being the most significant. Together, these factors determine the size of a mortgage that can realistically be serviced by a household.

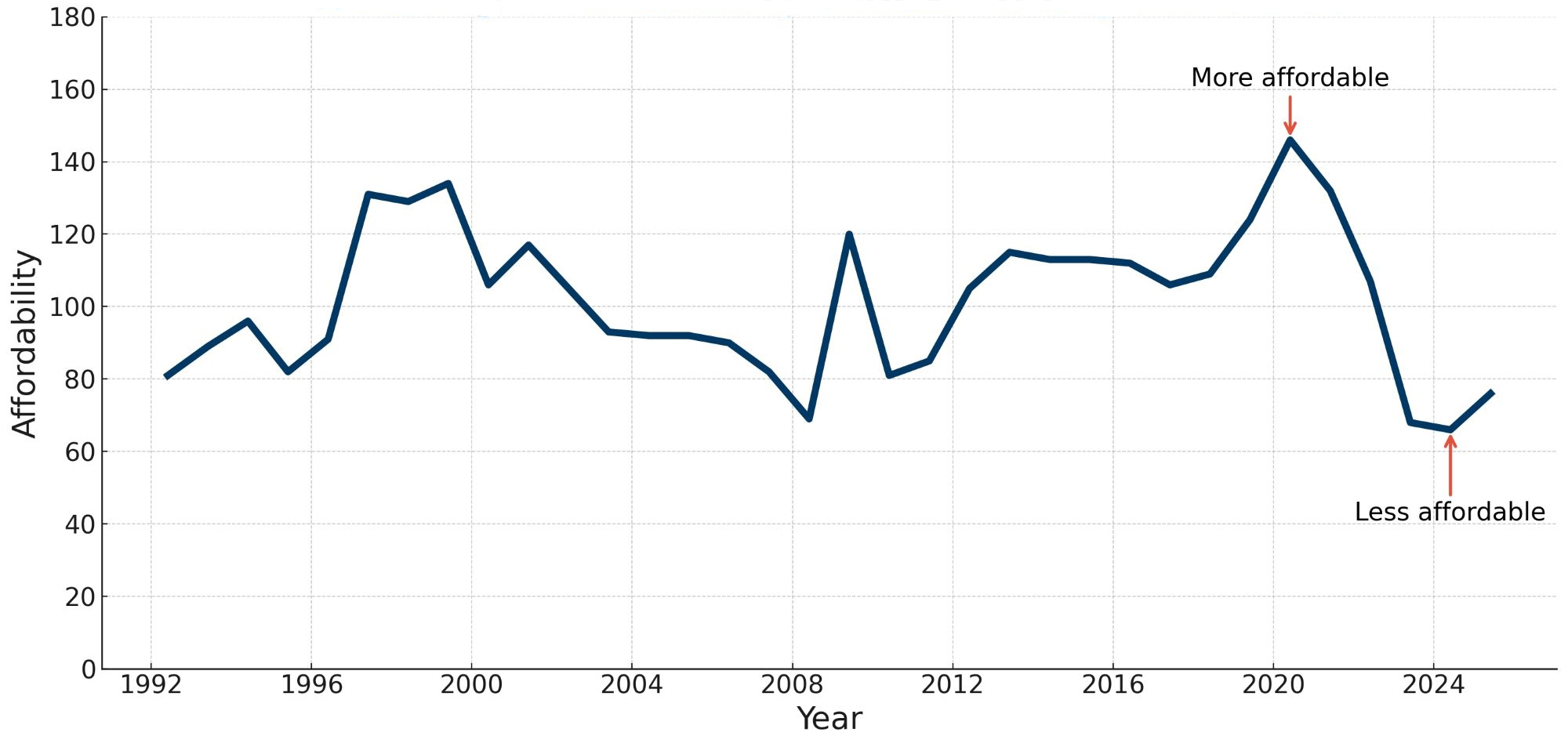

To capture this dynamic, we have developed a housing affordability index that reflects the relationship between these variables over the past 30 years. The below points explain how we construct our affordability metric:

- The mortgage rate represents the opportunity cost of homeownership, reflecting the potential return owners forgo by not investing their equity elsewhere. Multiplying the current house price by the mortgage rate gives today’s opportunity cost in dollar terms.

- A household’s average income indicates its ability to service that opportunity cost, with higher incomes enabling greater housing affordability. Dividing household income by the opportunity cost creates our housing affordability metric, which we index to 100 based on the average value over the time series.

The index is essentially a measure of the changes over time in the financial burden faced by households of owning a home.3 The chart below presents our housing affordability index for the combined eight capital cities, where a higher index value indicates greater affordability. While the index shows natural fluctuations, it has remained remarkably stable over the past 30 years despite the sevenfold increase in prices during the same period. In fact, every short-term deviation from the index base value of 100 has resulted in a medium-term correction.

Figure 2 - Housing Affordability Index - 8 Capital Cities

Source: FTI Consulting analysis of ABS and RBA data

According to our index, housing has been particularly unaffordable during three key periods:

- In the early 1990s, when mortgage rates exceeded 10%.

- In the lead-up to the Global Financial Crisis (“GFC”), when most assets were overvalued and the Reserve Bank of Australia (“RBA”) raised interest rates to combat inflation.

- In recent years, following strong property price growth since Covid — driven by increased demand for dwelling space, rising construction costs and further cash rate hikes occurred in response to inflation.

With recent and potentially future rate cuts alongside rising incomes, we expect affordability to gradually improve. However, this does not mean it will be easy for first home buyers to enter the market.

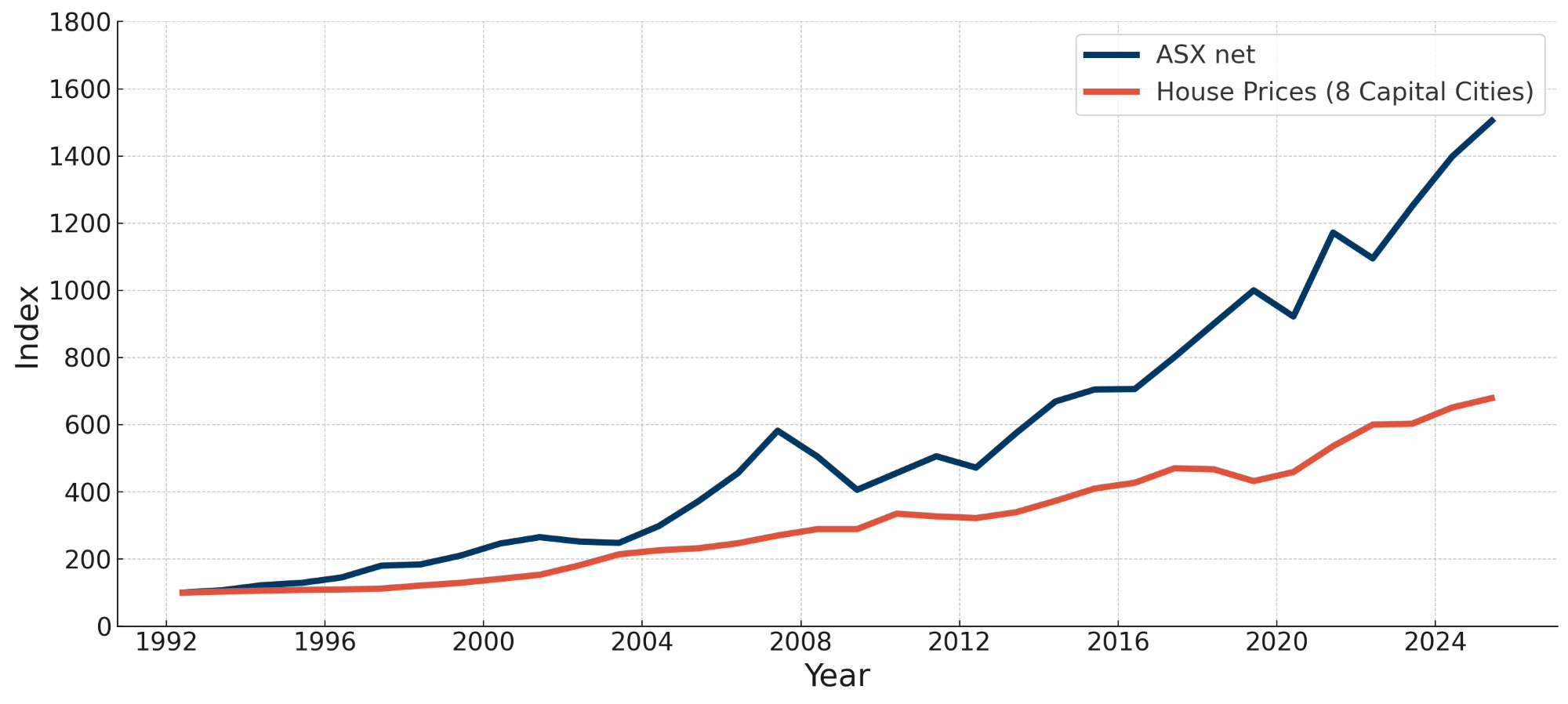

Housing vs Shares: Comparing Long-Term Value Growth

But how does housing stack up against other investment strategies, such as shares? Comparing the growth in house values to the ASX 200 over the 30-year period from 1992 to today, equities have clearly delivered stronger returns4 - almost double that of housing.

Figure 3 - Asset Value Growth (Base Year: 1993 =100)

Source: FTI Consulting analysis of ASX and ABS data

However, this direct comparison overlooks a critical aspect of housing investment: leverage. First homebuyers typically contribute a deposit of 10-20% and finance the remainder through a mortgage. As a result, any increase in property value significantly amplifies the return on their equity. For example, with an 80% loan-to-value ratio (“LVR”), a 10% increase in property value translates to a 50% gain on the homeowner’s equity. In contrast, most share market investors do not use comparable levels of leverage and do not experience the same magnified returns. This makes it useful to explore how different investment strategies impact long-term wealth accumulation for renters and buyers in a way that places both options on more equal footing.

Framework for Comparing Renting and Buying in the Australian Housing Market

The following analysis compares two representative individuals who begin with the same income and savings, but make different housing decisions:

- Buyer: This individual uses savings to put down a 20% deposit on an average unit in their suburb and pays the applicable stamp duty and associated fees. They live in the property for ten years, covering mortgage principal and interest, maintenance and strata fees, insurance and council rates. Upon selling the property, they also incur selling costs.

- Renter: This individual chooses to rent a similar property in the same suburb. While paying rent and standard tenant costs, they invest the upfront costs avoided by not purchasing (such as the deposit, stamp duty and fees) using a margin loan to create a 50% leveraged investment in an ASX ETF. Ongoing savings on outgoings, compared to the buyer, are also invested with 50% leverage, net of margin loan interest.

We model both individuals starting in Q4 2014, living in their respective dwellings for ten years then liquidating all assets in Q4 2024 (paying all applicable taxes and levies) and compare their financial outcomes. This simulation is then repeated for every quarter dating back to 1991, across 42 local government areas (“LGA”) in Greater Sydney, the Central Coast, Newcastle and the Illawarra, using data for both houses and units. The result is a wide sample of outcomes across time and location, providing a solid indication of how often each housing choice outperforms the other as a living and investment strategy.

Rent vs Buy: Long-Term Results Across Australia’s Housing Market

Our analysis covers 182 time periods across 42 LGAs in New South Wales and considers both houses and units — resulting in over 7,500 scenarios. For example, a house buyer purchasing in the Inner West in Q1 1995, would have seen their property value triple by 2005, yielding a nominal equity gain of $190,000. In contrast, a renter in the same suburb over that period would have gained only $73,000. Conversely, a house buyer in Camden in Q4 2014 would have built $64,000 in wealth by 2024, while a renter in that suburb would have accumulated $206,000.

Overall, our findings show that buyers come out ahead of renters about 60% of the time, which is surprisingly infrequent given the common perception that homeownership is the primary path to wealth. This analysis helps illustrate two key factors explaining why, in reality, renters often lag behind owners in wealth accumulation:

- Savings discipline: Homeownership typically enforces a higher savings rate through regular mortgage payments.

- Investment strategy: Mortgages leverage returns on equity, effectively boosting gains. Few renters use a comparable leverage, such as a 50% margin loan, which carries similar risk to an 80% mortgage.

This analysis does not aim to promote one housing strategy over another but rather to shed light on the reasons homeowners often build wealth faster than renters. Our results suggest that wealth growth is driven less by homeownership itself and more by the combination of leveraged investment and the ‘forced’ savings discipline imposed by regular mortgage payments. Importantly, similar financial discipline and leveraged investment can be achieved by renters who invest wisely, such as through margin loans in the share market, while maintaining consistent saving habits.

What This Means for Renters and Buyers in Australia

The finding that homeownership is not the only pathway to financial security carries important considerations for policies and programs. If the intention of these is to encourage wealth creation for retirement, a more equitable approach would be to create or support the use of vehicles in which all households can participate, irrespective of homeownership.

Conversely, if the aim of first home buyer support is to address housing affordability challenges, it is unclear whether it effectively targets those most in need. In 2021, over one-third of renters in capital cities experienced rental stress, while fewer than 15% of mortgage holders faced mortgage stress. While 35% of renters fell into the lowest quartile of social and economic disadvantage, fewer than 5% of mortgage holders do. This highlights that the core housing affordability crisis is less about renters being unable to buy and more about the difficulties many tenants face in meeting rental costs.

These insights suggest that housing affordability policies could be more effective if they place greater emphasis on expanding off-market rental options, such as affordable and social housing, to support those in greatest need, while also broadening access to effective, tax efficient retirement savings options that are not limited to those who can afford to buy a home.

How FTI Consulting Can Help

Both Federal and State Governments are continuing to develop and introduce policies and programs to help address the current housing affordability crisis. The Economic & Financial Consulting team at FTI Consulting has an in-depth understanding of the economics of the housing market. We can help organisations understand and respond to affordability challenges by:

- Understanding and defining the underlying housing affordability problems to be addressed – We recognise that an effective policy response depends on correctly defining the problem, whether it is declining homeownerships or worsening housing affordability.

- Designing and modelling policy responses – We assist in developing policy and program responses, as well as modelling their impacts on various cohort groups.

- Assessing outcomes, including unintended consequences – We evaluate the outcomes of policy responses to well-defined problems, focusing on targeted cohorts while also anticipating and mitigating any unintended consequences.

- Communicating the net public value a proposed development delivers to the community — Encompassing both the general and site-specific impacts of a development, such as enabling more productive use of land, improved amenities, better pedestrian access, adaptive heritage reuse and precinct benefits.

- Conducting comprehensive cost-benefit analysis, evaluation and assessment - Of urban renewal projects, affordable housing, social housing and infrastructure projects, incorporating all aspects of societal costs and benefits at a site-specific level.

Footnotes:

1: Link.

2: Taylor, David, “A generation of renters is staring down poverty in retirement unless something drastic changes.” (ABC News Australia) March 15, 2024.

3: Note that the index measures the changes in opportunity cost of owning a home, not the financial barriers to buying a first home - such as the size of the deposit needed.

4: The ASX index assumes reinvestment of dividends and is net of withholding tax and an assumed 15% capital gains tax.

Published

September 15, 2025

Key Contacts

Key Contacts

Managing Director

Senior Director

Senior Director

Director

Most Popular Insights

- Beyond Cost Metrics: Recognizing the True Value of Nuclear Energy

- Finally, Pundits Are Talking About Rising Consumer Loan Delinquencies

- A New Era of Medicaid Reform

- Turning Vision and Strategy Into Action: The Role of Operating Model Design

- The Hidden Risk for Data Centers That No One is Talking About