It’s Official — The 2020 Recession Was a Blip

-

October 12, 2021

DownloadsDownload Article

-

While most restructuring professionals recognize that the pandemic-induced recession ended sometime in 2020, few of us had any idea how quickly it was over — technically speaking. The Business Cycle Dating Committee of the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), the arbiter of business cycles, declared in late July 2021 that the recession ended after April 2020.1 (The NBER likes to take its time making these calls. It announced in September 2010 that the 2008-2009 recession had ended in June 2009.) That’s right, it was a two-month recession, the shortest in our nation’s recorded history.2 Measured on a quarterly basis, it was over before the end of 2Q20. The previous shortest recession lasted six months back in 1980.

The NBER acknowledged the unique characteristics of this latest recession, namely its severity and brevity. In some respects, the severity of the decline in economic activity in March-April 2020 contributed to its brevity, as the business cycle is measured on the basis of consecutive monthly or quarterly performance (rather than YOY), and it was highly unlikely the economy would continue to contract after those very harsh early months of the pandemic, barring a bubonic plague-type scenario. Economic growth resumed in May 2020, though the lingering effects of the recession were felt throughout the year.

We don’t mean to downplay the financial toll that COVID-19 took on millions of lives and businesses, but far more Americans were shielded from its impacts and, with the exception of the travel & leisure sector, the pandemic did not herald the cessation of economic activity that some were girding for. As we’ve said previously, our nation spent most of the last year climbing out of that early deep ditch and has been clawing its way higher ever since. It was clear by late summer of 2020 that the U.S. economy was gaining traction despite COVID-related restrictions and altered lifestyle choices. The 2020 holiday season was a strong one compared to 2019, despite the winter surge of the virus and a disappointingly slow start for the vaccine uptake at that time. More recently, real GDP surpassed its 2019 high of $19.2 trillion in 2Q21, two quarters ahead of most forecasts made back in mid-to-late 2020. By that measure, we are out of the ditch, though millions of struggling small businesses and still-unemployed Americans would disagree with that assessment.

The unprecedented federal response to the economic impact of the pandemic in the form of financial relief to states, individuals, and businesses, coupled with the speedy development and rollout of a vaccine, gets much of the credit for containing the fallout of the recession. But the real hero of the story is technology, which enabled a vast majority of Americans to work and transact from home during many months of mostly stay-at-home living, thereby containing the downturn to certain segments of the economy. Moreover, the financial savings of a work-from-home lifestyle were not insignificant for many millions of households. Most working Americans never missed a beat or a paycheck in 2020, and many enjoyed a sizeable financial windfall during the pandemic, a somewhat distasteful topic that garners little discussion.

Corporate Default Cycles Track Closely with Recessions Most of the Time

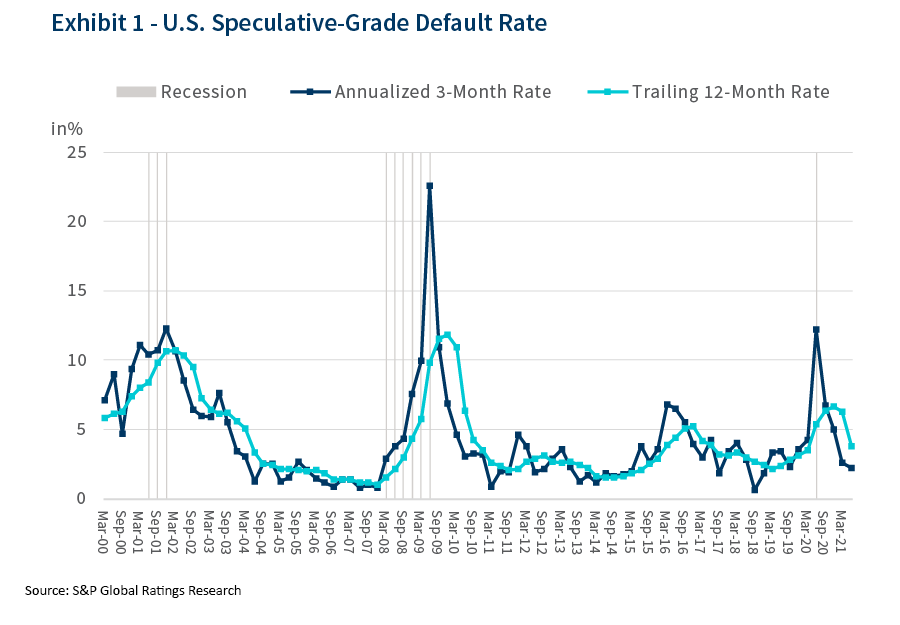

Business default cycles accompany recessions but rarely mirror them in timing or duration, and 2020 was no exception. The corporate default cycle that accompanied the 2020 recession is also over, and didn’t come close to matching the peaks of previous cycles (Exhibit 1). Nonetheless, defaults and bankruptcies hit a decade-high last year before steadily falling since September 2020. In retrospect, the default cycle of 2020 looks a lot like that of 2009, punctuated by a brief but intense burst of default activity (only less intense this time) followed by a quick resolution.

Both these default cycles were precipitated by extreme shock events that imperiled the global economy, with unprecedented federal policy responses helping to avoid a worst-case scenario in both instances. The heyday of the 2020 default cycle now seems like a distant memory, with defaults and filings trending lower throughout 2021, commercial bankruptcy filings (all sizes) recently hitting their lowest totals since 19853, and large corporate filings tracking for a slightly below-average year at best.

The distinguishing attribute of the last two default cycles compared to conventional ones was their sudden surge and fast fade, as evidenced by the sharp divergence between the default rates calculated on a trailing fourquarters basis (LTM) and the annualized quarterly default rate (Exhibit 1). Compare that to the default cycle of 2001- 2003, when these two default rate calculations moved nearly in tandem over a three-year period, with default activity elevated but undramatic. It’s a stark contrast.

The 2001 recession was a conventional cyclical downturn, the last “normal” recession we’ve had in twenty years, set off by the dot-com bubble bust but fueled by a prolonged earnings slump across the corporate sector. What that default cycle lacked in drama it made up for in duration, with the U.S. speculative-grade default rate staying above 5.0% for three consecutive years — long after that recession had technically ended in late 2001. With little fanfare, those 36 months produced 320 U.S.-based defaults compared to 220 in 2008-2009 and 145 in 2020.4

The manic nature of the last two cycles triggered defaults and bankruptcies in abundance but nonetheless was not entirely beneficial for the restructuring profession, given the difficulties presented around planning, hiring and staffing decisions amid a challenging forecasting environment and its whipsaw potential. A slower and steadier default cycle that is less erratic and more predictable better serves our profession but is no longer the reliable cyclical event it was in decades past, when recessions occurred once every six years or so.

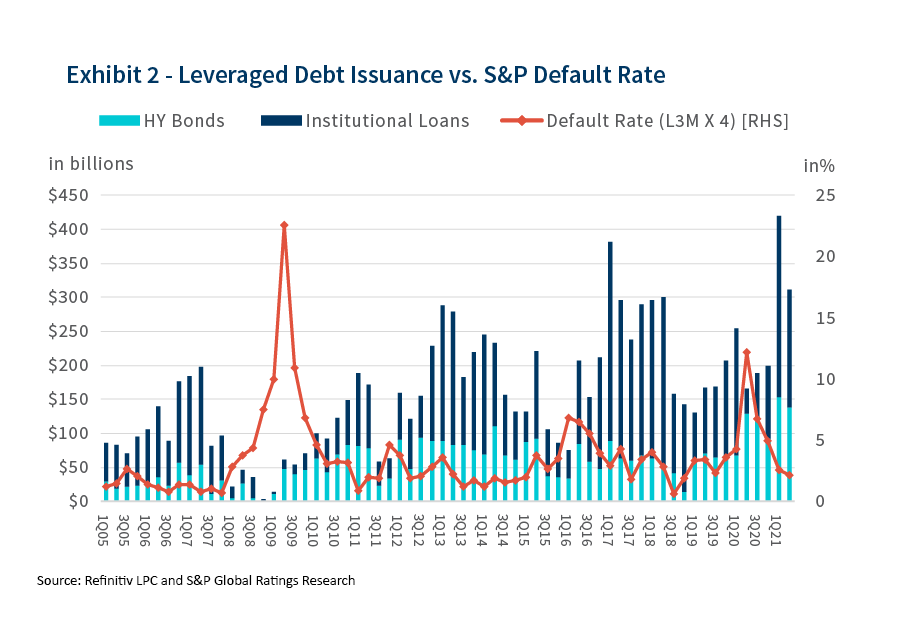

Aggressive federal policy responses and interventions in the private sector have become the expectation of financial markets and the corporate sector even as their diminishing efficacy going forward is debated. Corporate credit markets turned around in mid-2020 on the mere announcement of Fed interventions and haven’t looked back since then. Leveraged debt issuance since mid- to late 2020 has been torrential (Exhibit 2), and this has contributed hugely to the falloff in filings and defaults.

Some have argued that the apparent remedy to this crisis has sown the seeds for the next one, as many teetering companies have been extended financial lifelines that arguably did little more than postpone a moment of reckoning. Perhaps that premise will be proven true in due time, but the timing and uncertainty around these eventual bad outcomes is too vague to anticipate or count on currently. If such a scenario does materialize, it will be considered a distinctly new default cycle despite its connection to the events of 2020-2021.

Where does that leave us currently? Leveraged credit markets remain in the midst of an issuance surge that has likely peaked in 2021, with high-yield bond issuance poised to shatter its previous all-time high set last year. Distressed debt levels remain exceptionally low. There is little historical precedent for a meaningful uptick or surge of default activity in close time proximity to an issuance peak. The closest instance was in 2007-2008, when debt issuance activity peaked in 2Q07, some eight months prior to the collapse of Bear Stearns and a little more than a year before the onset of the global financial crisis in September 2008 (Exhibit 2). Despite some market rumblings of late, it would be wishful thinking to make the argument that the other shoe is getting ready to drop anytime soon with respect to a resurgence of restructuring activity.

Footnotes:

2: US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions | National Bureau of Economic Research (nber.org)

3: Bankruptcy Filings Plunged to Lowest Number Since 1985 | United States Courts (uscourts.gov)

4: S&P Global Ratings Research

Related Insights

Related Information

Published

October 12, 2021

Key Contacts

Key Contacts

Global Chairman of Corporate Finance

Downloads

Most Popular Insights

- Beyond Cost Metrics: Recognizing the True Value of Nuclear Energy

- Finally, Pundits Are Talking About Rising Consumer Loan Delinquencies

- A New Era of Medicaid Reform

- Turning Vision and Strategy Into Action: The Role of Operating Model Design

- The Hidden Risk for Data Centers That No One is Talking About