The Time for Change Is NOW

Part 1 of 2: Change Management

-

January 19, 2022

DownloadsDownload Article

-

A rapidly aging population combined with physician shortages, hospital/health system direct employment models and the evolution of value-based care highlight an opportunity for the transformation of primary care. While this opportunity has existed for quite some time, it has just recently gained criticality with the confluence of these factors.

The roadmap for the transformation of primary care began in 2007, when the American College of Physicians, the Academy of Pediatrics and the American Academy of Family Physicians issued the “Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home” (PCMH), establishing an approach to care that was patient-centered, comprehensive, coordinated, accessible, and committed to quality and safety1,2,3.

More than 10,000 practices with 50,000 clinicians are recognized by the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) PCMH program4. This represents nearly 23% of internists and family practitioners in the United States5.

In this article, we discuss the catalysts for change, evaluate the capitated business model currently in use, and discuss the parameters (and barriers) for primary care transformation. Then we make the case for accelerated implementation in the currently evolving ecosystem.

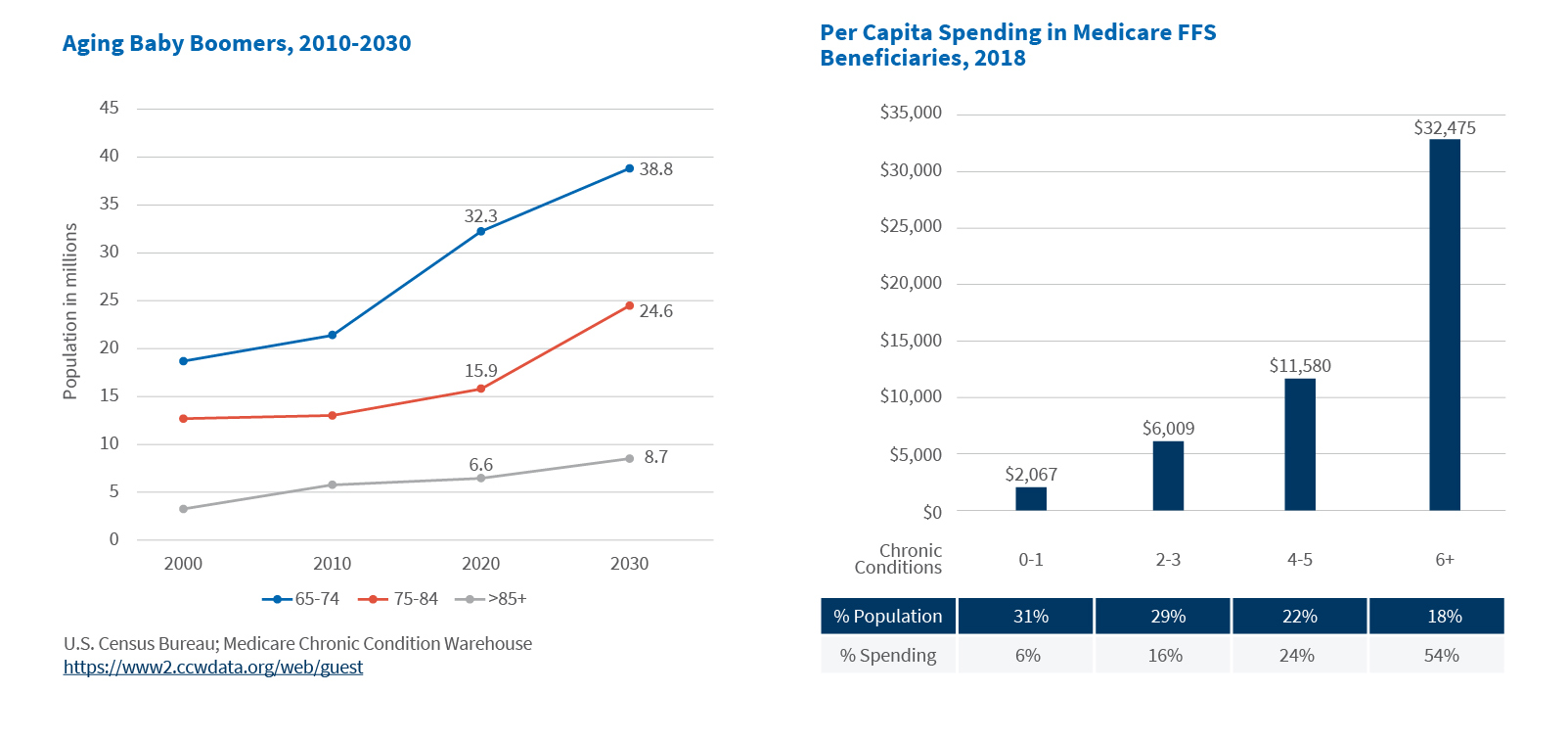

A rapidly aging population increases demand for chronic care (other) services

The U.S. population is aging rapidly, with an anticipated increase of the 65+ population from 56.1 million in 2020 to 73.1 million in 20306. Growth is highest for the 75-84 cohort at a compound rate of growth (CAGR) of 4.4%, followed by the 85+ (3.1%) and 65-74 (1.7%) cohorts7. The 65+ population is projected to make up approximately 20% of the total population by 20308.

Medicare expenditures are forecast to reach $1,559.4 billion in 2028, with spending per enrollee reaching $20,751. In 2020, total expenditures were $858.5 billion and spending per enrollee was $13,9099. The rapid rise in spending per enrollee primarily reflects the rising chronic disease burden, i.e., the number of chronic conditions as well as severity.

Aging population associated with rising chronic disease burden

Per capita expenditures increase with age and the number of chronic conditions, with six or more chronic conditions being an inflection point for spending. Medicare costs are concentrated: 18% of beneficiaries (with six or more chronic conditions) account for 54% of costs10. Conversely, 60% of beneficiaries account for 22% of costs11. The chronic disease life cycle is typically progressive, subject to acute, intermittent events and best managed by primary care physicians.

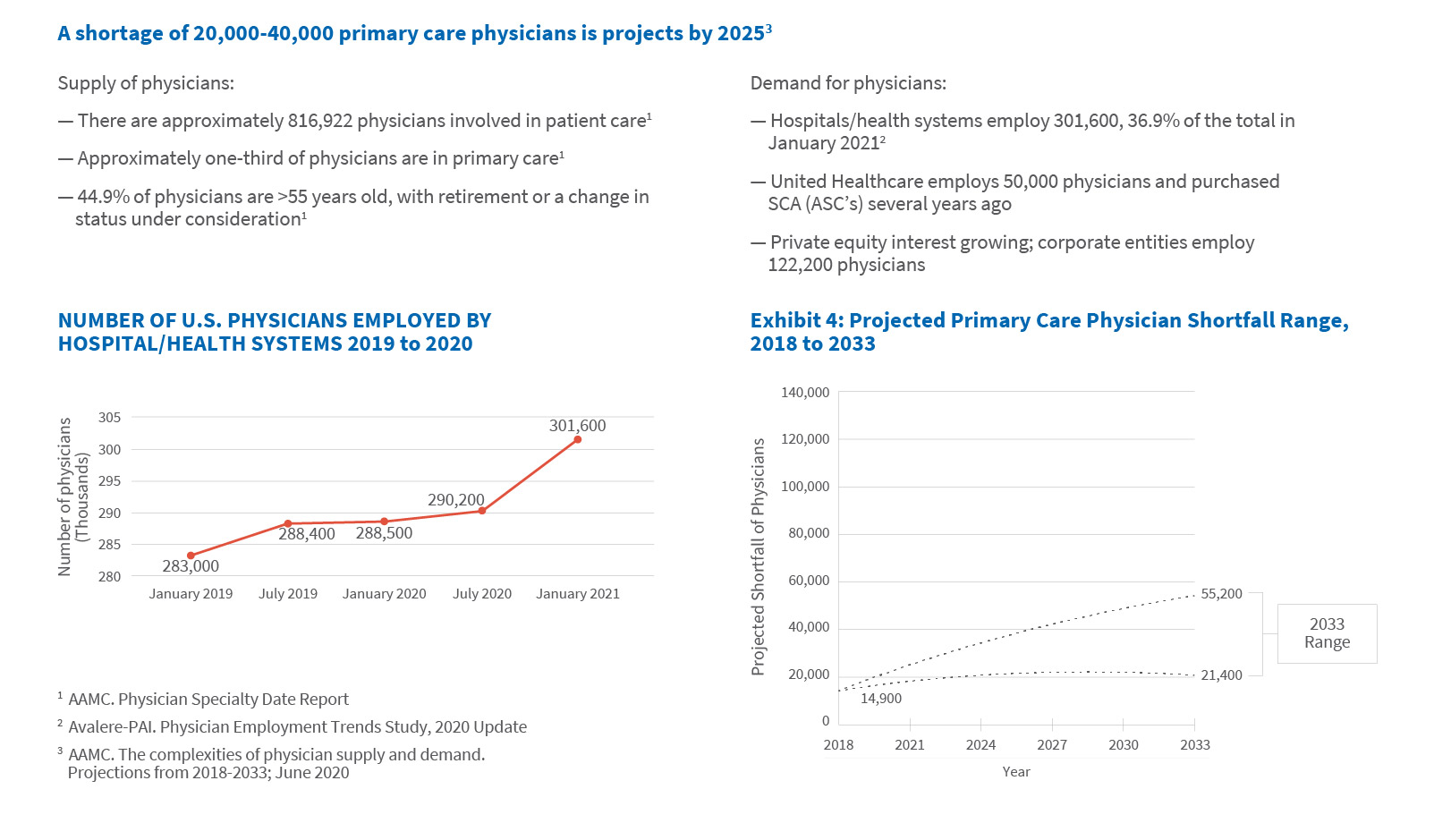

Physician employment trends require institutional leadership

Independent physician practices are disappearing as hospitals and health systems, payers and private equity firms purchase physician practices. As of January 2021, 36.9% of active, patient care physicians were employed by hospitals12,13. Corporate entities, including private equity, employ 122,000 physicians or approximately 15.0% of the total14. A single major insurer alone employs more than 50,000 employed or affiliated (data-driven) physicians and has a broad range of ambulatory capabilities, including ambulatory surgical centers15.

The American Association of Medical Colleges projects a shortage of 22,000-38,000 primary care physicians by 202516. This shortage may be compounded by early retirements caused by burnout associated with the COVID-19 pandemic17.

Physicians increasingly employed by hospitals/health systems and to a lesser extent, corporate equities (insurance companies, private equity)

Value-based initiatives adding risk

Value-based initiatives are being driven by Medicare; its focus on value-based reimbursement will gain urgency as the population ages and costs rise.

A common structure used to manage value-based initiatives is an Accountable Care Organization (ACO), “comprised of groups of doctors, hospitals, and other health care providers and suppliers who come together voluntarily to provide coordinated, high-quality care at lower costs to their Original Medicare patients18.” In 2021, approximately 11.9 million Medicare beneficiaries were enrolled in 512 ACOs; 10.7 million (90 percent) in a Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) and 1.2 million (10 percent) in Next Generation ACOs19,20,21. Most ACOs have multiple participating providers comprising hospitals, health systems, physician groups and solo practitioners.

Other value-based initiatives include Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015, which altered the physician payment model with its two-track Quality Payment Program (MIPS, APMs); the Direct Contracting model for traditional Medicare beneficiaries, offering both capitated and partially capitated population-based payments; and Primary Care First, which is “oriented around five comprehensive primary care functions: (1) access and continuity; (2) care management; (3) comprehensiveness and coordination; (4) patient and caregiver engagement; and (5) planned care and population health22,23,24,25.”

Medicare Advantage: A potential source of capitated provider payments

In 2021, 26.4 million seniors (42% of Medicare beneficiaries) enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans26. The Congressional Budget Office forecasts a 46% penetration rate by 202527. Five companies account for nearly 80% of the market28. Medicare Advantage plans are incentivized to use care management techniques to deliver more efficient care, since they are paid on a predetermined rate per risk-adjusted enrollee. Plans also can negotiate payment methods with individual providers. Total Medicare payments to MA plans (including rebates that finance extra benefits) average an estimated 104 percent of Fee-for-Service spending29.

Value-based, patient-centric networks of primary care centers for Medicare-eligible patients have opened30. Through a proactive and personalized approach to care delivery, supported by technological advancement, providers have been able to reduce the hospitalization and re-admission rates and total emergency department visits relative to fee-for-service benchmarks. They negotiate a capitated rate with MA plans and are financially responsible for all subsequent medical expenditures. Scale is necessary to reduce the impact of random spending fluctuations in the attributed population.

Principles of effective primary care practice are known

Common elements have emerged among the various frameworks (e.g., patient-centered medical home) for the effective and efficient delivery of primary care, including:

- Organizing care delivery around the care continuum (i.e., transitions of care)

- Enhancing access

- Broadening the scope of healthcare providers (from disease management to whole-person care)

- Redefining the role of the primary care physician from autonomous actor to an integrated team leader

- Delivering evidence-based clinical care and effectively using care management to support high-needs patients

- Introducing complex new workflows and technologies

- Adopting IT infrastructure and analytic capabilities to track patient quality and cost outcomes

- Evolving financial management systems to manage risk-based contracts, and

- Aligning governance and management processes to support alternative payment and care delivery31.

The “Triple AIM” — improving the health of populations, reducing the per capita cost of care and improving the individual experience of care – represents the guiding principle for change32. Managing the total cost of care is essential. The chronic disease life cycle is typically progressive, subject to acute, intermittent events and best managed by primary care physicians; 50% of Medicare spending takes place in acute episodes of care to 90 days post-discharge33. Avoidable admissions are critical. Social determinants matter.

Execution challenges are significant and one too many

Organizational culture, workflow integration, clinical continuity, and transition management and near-term financial performance pose a series of challenges to healthcare leaders.

Physicians are required to reinvent themselves, from independent, acute interventionists focused on fee-for-service (volume) performance to integrated team leaders who are prevention-oriented, proactive and focused on value (quality/cost). Physician compensation requires alignment to organizational goals and objectives.

Workflow integration for chronic disease management requires real-time data, proactive management and clearly defined roles for care team members.

Transitional care management may require additional support staff (i.e., a case manager) closely monitoring patient progress. Patient bundles include the immediate post-operative period. Post-acute care- and hospital-at-home provide emergent opportunities for non-facility care.

Capital investment in new technologies may be required. Platforms have applications (a) at the front end to enhance access and patient satisfaction (i.e., contact centers); (b) as an analytic engine to facilitate population health (risk stratification, gaps in care, predictive modeling, benchmarking) and quality/outcome reporting; (c) to facilitate care management — the identification of patient-specific tasks, goals and assessments; (d) to integrate remote monitoring data; and telehealth.

Managing risk and the timing of transition from fee-for-service to value is challenging; a reduction in revenue prior to a proportionate decline in (fixed) expenses may occur.

Bottom line: The future is now

Primary care will emerge as the epicenter of a value-based ecosystem proactively managing patients with multiple (chronic disease) co-morbidities. Fewer hospital admissions, re-admissions and emergency department visits are likely to result. This is particularly challenging for hospitals and health care systems employing physicians focused on reactive, acute interventions.

It has been nearly 15 years since the Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home were published. Much has changed since then, but a predominantly fee-for-service reimbursement system has persisted. Given rapidly rising costs, the current healthcare delivery system is not sustainable. It’s time for a change.

Footnotes:

1: Alice Shepherd. Patient-Centered Medical Homes: An Old Concept Gets Recharged. For the Record, Vol 17 (22); Sept 13, 2010. https://www.fortherecordmag.com/archives/091310p12.shtml

2: Defining the Medical Home. Primary Care Collaborative. https://www.pcpcc.org/about/medical-home

3: Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home. American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Physicians; March 2007 https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/practice_management/pcmh/initiatives/PCMHJoint.pdf

4: NCQA Patient-Centered Medical Home. https://www.ncqa.org/programs/health-care-providers-practices/patient-centered-medical-home-pcmh/

5: AAMC Active Physicians in the Largest Specialties, 2019 https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/active-physicians-largest-specialties-2019

6: U.S. Census Bureau. Projected Age Groups and Sex Composition of the Population. Projections for the United States: 2017 to 2060. Datasets: Main Series. Table 2 https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/demo/popproj/2017-summary-tables.html

7: U.S. Census Bureau. Projected 5-Year Age Groups and Sex Composition of the Population. Projections for the United States: 2017 to 2060. Datasets: Main Series. Table 3 https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/demo/popproj/2017-summary-tables.html

8: Demographic Turning Points for the United States: Population Projections for 2020 to 2060. Revised February 2020. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2020/demo/p25-1144.pdf

9: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, National Health Expenditures, Projected; Table 17. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsProjected

10: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Chronic Conditions Charts: 2018 https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Chronic-Conditions/2012ChartBook

11: Ibid.

12: Tara Bannow. Nearly 70% of U.S. physicians now employed by hospitals or corporations, report finds. Modern Healthcare; June 29, 2021. https://www.modernhealthcare.com/providers/nearly-70-us-physicians-now-employed-hospitals-or-corporations-report-finds

13: AAMC Physician Specialty Data Report, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/active-physicians-largest-specialties-2019

14: Physicians Advocacy Institute. Avalere Report on Physician Practices and Employment 2019-20. http://www.physiciansadvocacyinstitute.org/Portals/0/assets/docs/Revised-6-8-21_PAI-Physician-Employment-Study-2021-FINAL.pdf?ver=K6dyoekRSC_c59U8QD1V-A%3d%3d

15: Optum has 50,000 employed, affiliated physicians and a vision for the future. Becker’s ASC Review; September 17, 2019. https://www.beckersasc.com/asc-transactions-and-valuation-issues/optum-has-50-000-employed-affiliated-physicians-and-a-vision-for-the-future.html

16: The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2019 to 2034. AAMC; June 2021. https://www.aamc.org/media/54681/download?attachment

17: Michael Dill. We already needed more doctors. Then COVID-19 hit. AAMC; June 17, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/we-already-needed-more-doctors-then-covid-19-hit

18: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Next Generation ACO Model. https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/next-generation-aco-model

19: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Shared Savings Program Fast Facts, as of January 1, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/2021-shared-savings-program-fast-facts.pdf

20: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Next Generation Payment Models. https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/next-generation-aco-model

21: National Association of ACOs. https://www.naacos.com/

22: American College of Surgeons, 2021 MACRA Quality Payment Program https://www.facs.org/advocacy/qpp/2021

23: American Academy of Family Physicians, Advanced Alternative Payment Models. https://www.aafp.org/family-physician/practice-and-career/getting-paid/aapms.html

24: “CMS Direct Contracting: Preparing for the New Model & How to Succeed with Real-Time Data”; White Paper. PatientPing.com. http://go.patientping.com/rs/228-ZPQ-393/images/PatientPing%20Direct%20Contracting%20White%20Paper.pdf

25: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Primary Care First Model Cohort 2 CY 2021 Fact Sheet, March 16, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/primary-care-first-model-cohort-2-cy-2021-fact-sheet

26: Medicare Advantage in 2021: Enrollment Update and Key Trends. KFF; June 21, 2021. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-advantage-in-2021-enrollment-update-and-key-trends/

27: Ibid.

28: Ibid.

29: MedPAC Report to Congress. Chapter 12; March 21, 2021. https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/import_data/scrape_files/docs/default-source/reports/mar21_medpac_report_to_the_congress_sec.pdf

30: Oak Street Health Corporate Presentation, May 2021. https://s25.q4cdn.com/801682165/files/doc_presentations/2021/05/OSH-May2021.pdf

31: Evolving Care Models; Aligning care delivery to emerging payment models. American Hospital Association Center for Health Innovation, 2019. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2019/04/MarketInsights_CareModelsReport.pdf

32: Institute for Healthcare Improvement Triple Aim Initiative http://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx

33: Keys to Managing Total Cost of Care for Acute Episodes, Sound Physicians Webinar. https://soundphysicians.com/webinar/5-keys-to-managing-total-cost-of-care-for-acute-episodes/

Related Insights

Related Information

Published

January 19, 2022

Key Contacts

Key Contacts

Downloads

Most Popular Insights

- Beyond Cost Metrics: Recognizing the True Value of Nuclear Energy

- Finally, Pundits Are Talking About Rising Consumer Loan Delinquencies

- A New Era of Medicaid Reform

- Turning Vision and Strategy Into Action: The Role of Operating Model Design

- The Hidden Risk for Data Centers That No One is Talking About