Has the U.S. Energy Sector Finally Learned Its Lesson? It Seems So.

-

February 10, 2022

DownloadsDownload Article

-

Old habits die hard if they die at all. We tend to relapse into bad habits a few times before finally kicking them for good. For the U.S. energy sector, its bad habit of undisciplined drilling activity whenever oil prices enjoy a heady rally has undermined the sector’s prosperity in boom times and brought the industry to its knees three times since 2009, resulting in nearly 550 energy-related bankruptcy filings since 20151.

That’s more than a bad habit, it’s an addiction — enabled by breakthroughs in drilling technology since 2005, namely horizontal drilling and pad drilling in unconventional oil plays, that made new well drilling more efficient and less costly. The temptation for energy producers to “drill, baby, drill” when oil prices are strong is understandable as much as it is irresistible.

In that respect, the U.S. energy sector has been a victim of its own success. For over a decade, independent energy producers were singularly focused on acquiring acreage and increasing drilling activity and production as oil prices consistently held above $75 per barrel and topped triple digits several times. Such investment activity was financed by internally generated cash flow and debt financing, causing industrywide leverage metrics to increase sharply in the last decade. Oil production from major continental shale plays and other tight oil formations made possible by these drilling innovations has more than doubled since 2010, making the United States the world’s leading producer of crude oil for the last several years. That incremental U.S. oil production — some six million barrels per day — combined with Saudi Arabia’s unwillingness to counter overproduction by other OPEC countries has been sufficiently large to have a notable impact on global supplies and oil prices, resulting in two damaging downcycles for the U.S. energy sector over the last six years, mostly due to oversupply.

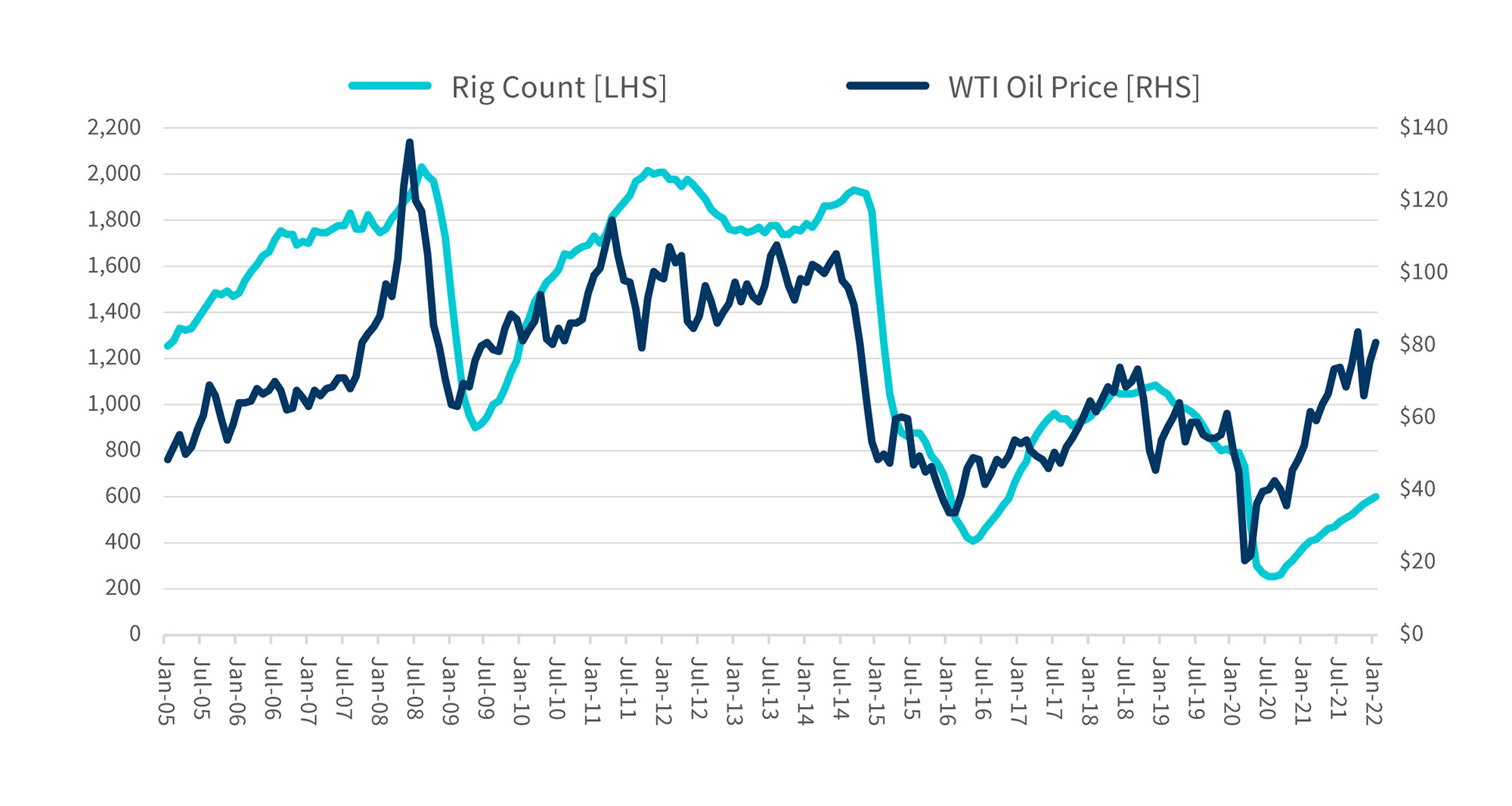

With WTI crude oil prices plunging by nearly 70% from peak to trough, the energy bust of 2015-2016 was a wipeout event for many independent E&Ps that ushered in a new directive from investors and creditors to cool off the unbridled drilling activity. The continental U.S. rig count fell from 1,900 active rigs in late 2014 to just 400 by mid-2016, a stunning decline of nearly 80% (Exhibit 1). But the drilling hiatus did not last long. By mid-2018, with crude oil prices recovering to the mid-$60 per barrel range, the U.S. rig count again surpassed 1,000 for the next 12 months — well below its pre-2015 peak but still a robust level of drilling activity. That prosperity was short-lived as oil prices weakened in 2019 and then collapsed with the sudden arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent supply war between Saudi Arabia and Russia. Drilling activity virtually ceased in the early months of the pandemic, hitting a multi-decade low of 250 active rigs in mid-2020, and set off another round of energy restructuring activity.

One year later, with an economic recovery well underway and many commodity prices rallying across the globe, the U.S. energy sector is again confronted with a familiar dilemma. However, the energy bust of 2020 might have been a moment of clarity for U.S. oil producers, who finally seem to understand the folly of their old ways and are showing surprising restraint in drilling activities this time around even as global energy prices surged in 2021. Moreover, access to capital for drilling activity by traditional lenders to the energy sector has been curtailed for a variety of reasons, prompting most independent E&P companies to redirect internally generated cash flow away from aggressive capital spending towards liability management, debt reduction and return of cash to shareholders. Industry consolidation was also prevalent since 2020, with several large energy M&A deals done in stock-for-stock transactions. Consequently, average U.S. oil production in 2021 fell by nearly 2 million barrels per day (BPD) compared to 2019’s peak of more than 13 million BPD2. Perhaps most impressive, energy-related Chapter 11 filings fell by 75% last year, and it appears stability has come to a volatile sector. Will it stay that way?

A recent article in Bloomberg News3 elicited a doubletake, with CEOs of several large, independent E&P companies expressing concern about rising oil prices, especially if prices were to again approach $100. The prevailing sentiment is that prices above $100 could spark a surge of new drilling activity and potentially create another supply imbalance, with the CEO of Pioneer Natural Resources going so far as to say that oil prices above $100 per barrel are “not going to help our industry.” That is quite an about-face from the mantra of “drill, baby, drill,” and other E&P CEOs went on record to say they remained committed to restraining production growth even as oil prices increase to their highest levels since 2014. They believe the current price range for oil prices is a sweet spot, high enough to be very profitable for E&Ps but low enough to discourage rampant new drilling. Actions often fall short of intentions, but E&Ps are living up to their word so far. The current U.S. active rig count is just 600—about half the peak of 2018—even as oil prices hover above $80 per barrel (Exhibit 1), an impressive display of discipline in an industry not known for self-restraint.

Exhibit 1 - U.S. Rig Count vs. WTI Oil Price

Source: FTI Consulting, Inc.

The news is not all good in the oil patch, as subdued drilling activity continues to afflict oilfield services companies, everyone from drillers to frackers to well tenders whose prosperity depends on healthy levels of well drilling. Strong oil prices don’t do them any good unless it encourages new drilling or well completion. The S&P 1500 Energy Equipment & Supplies Industry Index remains 11% below its pre-pandemic value compared to the S&P 1500 Oil & Gas Index, which is 12% above its pre-COVID level. This relative outperformance makes perfect sense, as the rebound in energy prices since mid-2021 has primarily benefited E&P companies, whose vast reserves are appreciably more valuable with oil prices holding north of $80 per barrel. For the rest of the energy complex, it is a waiting game.

The prospect of oil prices at least holding steady or moving higher over the balance of 2022 is favorable given the ongoing global recovery from COVID, heightened Western tensions with Russia over Ukraine and political or social unrest in some key oil producing nations, such as Kazakhstan. Drilling activity certainly will continue to rebound if prices hold, but it seems highly doubtful that new drilling will approach levels last seen when oil prices were this high — and even 1,000 active rigs seems like a high bar to reach this year.

The U.S. energy sector has accounted for a highly disproportionate share of distressed debt and restructuring activity since 2015 relative to its weight in most major market indexes. In absolute numbers, it has been a perennial leader among all industry sectors in Chapter 11 filings since 2015, but the energy sector is ready to hand off that baton to somebody else in 2022 provided it can stick to its guns.

Footnotes:

1: Haynes Boone, Energy Roundup

2: U.S. Energy Information Administration, U.S. Field Production of Crude Oil, December 2021

3: Bloomberg, Shale CEOs Say $100 Oil Would Upset Industry’s Delicate Balance, January 5, 2022

Related Insights

Related Information

Published

February 10, 2022

Key Contacts

Key Contacts

Global Chairman of Corporate Finance

Downloads

Most Popular Insights

- Beyond Cost Metrics: Recognizing the True Value of Nuclear Energy

- Finally, Pundits Are Talking About Rising Consumer Loan Delinquencies

- A New Era of Medicaid Reform

- Turning Vision and Strategy Into Action: The Role of Operating Model Design

- The Hidden Risk for Data Centers That No One is Talking About