Is Inflation as Bad as the Headlines Indicate?

Not Really, but It Is Still a Problem

-

March 14, 2022

DownloadsDownload Article

-

The U.S. economy is confronting a spike in inflation for the first time in four decades, which means that most Americans have never experienced it in their adult lives until now. The near absence of inflation for decades is no coincidence or happy accident.

Our national experience with inflation and stagflation during the “lost decade” of 1973-1982 was so dreadful and injurious to our economy that policy advisors and monetary policy officials have since been ever vigilant about containing inflation — that is, until recent years when inflationary concerns took a backseat to worries over financial market instability and economic stagnation, and some key policymakers began to believe that the monetary laws of gravity no longer applied. The lost decade was arguably the worst economic period of the post-War era for the United States, and those who remember it firsthand have a deeper appreciation of inflation’s damaging effects than those who did not live through it.

Cable news channels do viewers a disservice with their coverage of inflation-related stories, rushing off to gas stations or supermarkets to interview harried drivers and shoppers every time another economic report points to rising prices. Such stories about “Average Joe” having to make painful spending choices every time he fills the gas tank help fill airtime during slow news cycles but provide little perspective. Yes, most consumers are telling pollsters they are concerned about rising prices, and technically it is true that the rate of inflation for consumer goods is at its highest level in 40 years, but that factoid needs some context before we start invoking any comparisons to the early 1980s. The media’s impression that inflation is wreaking havoc with consumers, most of whom were recipients of large stimulus payments last year and continue to spend aggressively, is exaggerated.

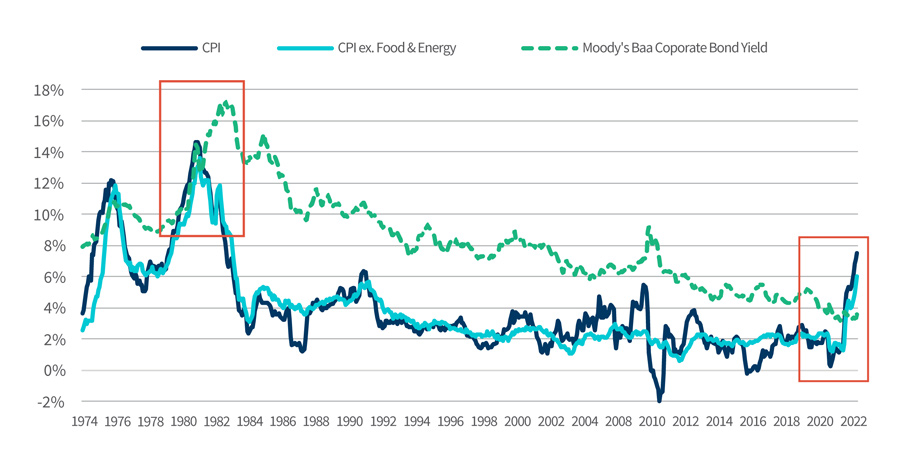

Moreover, the consumer-level inflation rate averaged 8.5% annually over the entirety of that lost decade of high inflation. At its worst point, from early 1979 to early 1981, the CPI index tallied 26 consecutive months of double-digit price increases (Exhibit 1). Now that is inflation—and it took a deliberate Fed-induced recession to tame that beast. The current bout of inflation we are experiencing, however long it may ultimately last, is still in the first round, having just begun in the second half of 2021.

Exhibit 1 – U.S. Consumer Inflation vs. Baa Corporate Interest Rate

Source: FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

The headline statistic getting all the media attention of late is the 7.5% YOY increase in the CPI Index for January 2022 (1) that punctuated a six-month trend of steadily increasing inflation. (The January CPI Index, excluding the volatile food & energy components, increased by a more modest 6.0% rate.) However, a huge spike in vehicle prices in 2021 (mostly due to chip shortages that curbed auto production), which comprise 8.2% of the CPI basket, had an outsized impact, adding 200 basis points to headline inflation rates. If you did not purchase a vehicle within the past year, your personal inflation rate was likely much less than 7.5%. Double-digit price increases for other highly discretionary items such as furniture, hotel rooms, tickets and car rentals contributed another 50 bps to the headline rate. In all, these items accounted for approximately 250 bps of inflation in 2021, so the cost increase of “regular living” was likely closer to 5.0% (still more than double the Fed’s inflation target and a concerning rate of increase for policymakers, but considerably lower than the headline number) while the Fed’s favored inflation indicator (the PCE deflator) is tracking close to 6.0%.

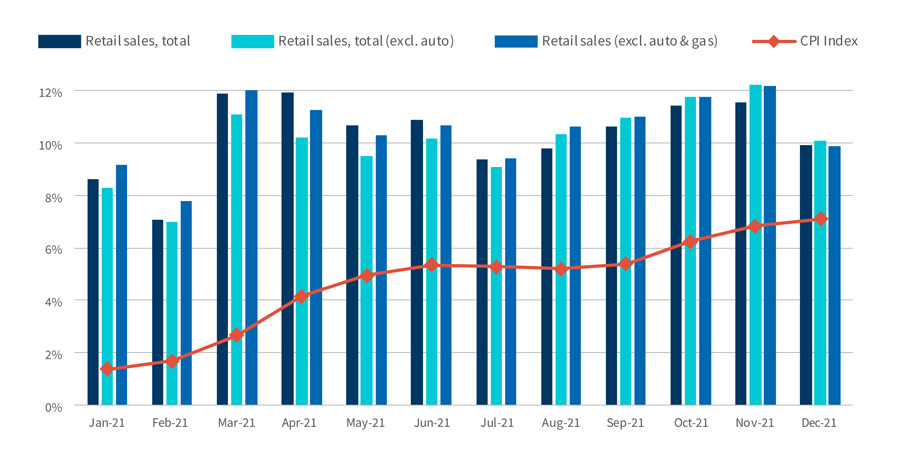

The inflation spike in 2021 almost certainly is attributable to an overstimulated economy. Congress and federal policy officials enacted massive financial relief measures and monetary stimulus to keep the U.S. economy from backsliding long after COVID effects had peaked. However, those concerns were overblown, and the economy was well along on its road to recovery in early 2021 when the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan (ARP) was passed. In all, federal relief measures paid to individuals topped $1 trillion1 in 2021, larger than the $800 billion paid out in 2020 when the pandemic hit hardest. Moreover, less of this financial relief in 2021 went to unemployment assistance while more money was sent in an untargeted way to most tax-filing individuals. Economic historians will likely blame the ARP for setting off inflation — not the cause per se, but a match thrown on kindling wood. The ARP quickly fueled an unprecedented consumer spending spree. Retail sales and inflation shot higher almost immediately after that third round of payments was made to individuals in March 2021 and have not slowed since then (Exhibit 2). Retail sales increased by nearly 18% in 2021, the largest annual increase on record, even as spending on services also began to recover. Any concerns about supply chain disruptions, a new COVID variant and rising prices putting a dent in the holiday season were unfounded and had virtually no impact on consumer spending, with holiday retail sales increasing by nearly 15%, also an all-time high. Consumer spending vigor has continued into 2022 despite the Omicron outbreak, and to date, there is little indication of any spending slowdown. For all their voiced concerns about rising prices, consumers continue to spend with abandon and have tolerated price increases passed on to them, which suggests more inflation is coming.

The most compelling argument against a transitory inflation scenario is strong jobs growth and wage increases, which combined to cause total wage income to jump by 9.1% last year, an income gain of nearly $1 trillion in 2021. Wage gains won by private sector workers have also accelerated, potentially setting up a wage-price inflation spiral. Add another $1 trillion in federal payments to individuals last year and there is a surfeit of personal savings capable of absorbing inflation hits for a while, with above-average personal savings totaling some $3 trillion in 2020-2021.

What is undeniably true today is that interest rates across the spectrum are far too low if inflationary expectations persist. Despite rampant inflation during the lost decade, real rates of return on Baa-rated corporate bonds were rarely less than zero and mostly positive, as nominal yields consistently rose to compensate investors for the diminishing purchasing power of the dollar (Exhibit 1). That world seems long gone, as the abundance of liquidity created by federal financial relief programs and the Fed’s massively stimulative policies since COVID struck have resulted in unnaturally low interest rates, often compromising rational investment decisions, while the U.S. dollar remains inexplicably strong even as inflation takes hold. This dynamic could not persist without these massive interventions. If current inflation rates are indicative of the eroding purchasing power of the dollar, then real rates of return on virtually all corporate debt have gone deeply negative in recent months, as nominal yield increases of 150 bps or so since late 2021 badly trail the uptick in inflation. Investors buying government notes or corporate debt in the current environment are accepting increasingly negative real yields if inflation is not tamed soon.

Exhibit 2 – Retail Sales Growth (2019-2021 CAGR) vs. Inflation

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

All eyes are on the Fed, which has acknowledged that slowing inflation is now its top policy priority. Base rate hikes, namely the Fed Funds rate, will begin this month, but how far and how fast these hikes occur has become a parlor game for Fed watchers and traders, many of whom expect a rate hike at most Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meetings this year. This could bring the Fed Funds rate close to 2.0% by year end from near zero, while the Fed’s balance sheet runoff will put upward pressure on Treasury yields.

However, the conflict in Ukraine has complicated the Fed’s policy decisions until the war’s global effects are better understood. Before that conflict suddenly began, many Fed watchers were expecting a vigorous Fed response to inflation — both in terms of rate hikes and balance sheet contraction — but now the potential for soaring energy prices to slow the economy likely has given pause to an aggressive course of Fed action (at least for now) that could be too oppressive if other macroeconomic factors also dampen growth.

Tighter monetary policy and rising interest rates are inevitable in 2022 regardless of the exact path the Fed chooses to take. The Fed has underestimated the risk of inflation over the last year or so and is compelled to take more aggressive action now that inflation has taken root. However, the outbreak of war in Ukraine could convince the Fed to proceed more slowly than needed. Corporate credit markets have been staying positive about the prospect of bringing inflation under control, but such patience has its limits and market rates of interest could take off if inflation is still running hot at year-end. The leveraged corporate sector is healthy enough to tolerate moderately higher interest rates, but distressed activity will pick up notably should rates move higher by another 200 bps or more, which does not seem like a longshot. One thing is certain: The Fed is about to turn the page on its great experiment with easy money, and nobody knows how this story will turn out.

Footnotes:

1: Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), Effects of Selected Federal Pandemic Response Programs on Personal Income, January 28, 2022

Related Insights

Related Information

Published

March 14, 2022

Key Contacts

Key Contacts

Global Chairman of Corporate Finance

Downloads

Most Popular Insights

- Beyond Cost Metrics: Recognizing the True Value of Nuclear Energy

- Finally, Pundits Are Talking About Rising Consumer Loan Delinquencies

- A New Era of Medicaid Reform

- Turning Vision and Strategy Into Action: The Role of Operating Model Design

- The Hidden Risk for Data Centers That No One is Talking About