The ‘Modern’ DCF Valuation Approach: Theory Versus Practice

-

December 05, 2024

DownloadsDownload Article

-

Reproduced with permission from Law Business Research Ltd. A previous version of this article was published in December 2022 and can be found here: https://globalarbitrationreview.com/guide/the-guide-damages-in-international-arbitration/5th-edition

Summary

The ‘Modern’ Discounted Cash Flow (‘DCF’) approach came to the arbitration community’s attention following the $4.1 billion Tethyan v Pakistan award issued in 2019. Like the standard DCF approach, the ‘Modern’, or certainty equivalent DCF approach is an income-based valuation approach, but how do the two methods differ and does the ‘Modern’ DCF approach actually have any real benefits?

- The only difference between the standard DCF approach and the ‘Modern’ DCF approach is in the way each method adjusts for systematic risks. While the standard DCF approach adjusts for these risks via the discount rate applied to expected cash flows, the ‘Modern’ DCF approach directly adjusts the expected cash flows for risk and then discounts them at the risk-free rate.

- The main theoretical appeal of the ‘Modern’ DCF approach is that it can, in principle, allow a valuer to rely on market signals, notably observed prices for futures contracts, to adjust a valuation for systematic risks. However, this relies on the existence of a liquid market for such futures contracts. In practice, futures contracts for commodities are not liquid beyond a few years, and there are no futures markets at all for many of the inputs which affect a project’s or company’s cash flows.

- Standards of value used in damages assessments in arbitration typically explain that the valuation approach should reflect the inputs and assumptions that would be adopted by market participants. This is problematic for the ‘Modern’ DCF approach which, despite existing for around six decades, does not appear to be commonly used.

What is meant by the ‘Modern’ DCF? What makes this valuation approach potentially appealing, in theory?

What are some relevant factors to consider when evaluating a valuation performed using the ‘Modern’ DCF approach? How does theory pan out in practice when it comes to implementation? As this method is not commonly used by market participants to value companies or projects, what relevance can this have to common damages assessments such as ‘market value’ and ‘fair market value’?

Income Approaches: Standard or Modern?

Under the income approach, the value of an asset is determined by reference to the present value of the future income stream that is expected to be generated by the asset.1

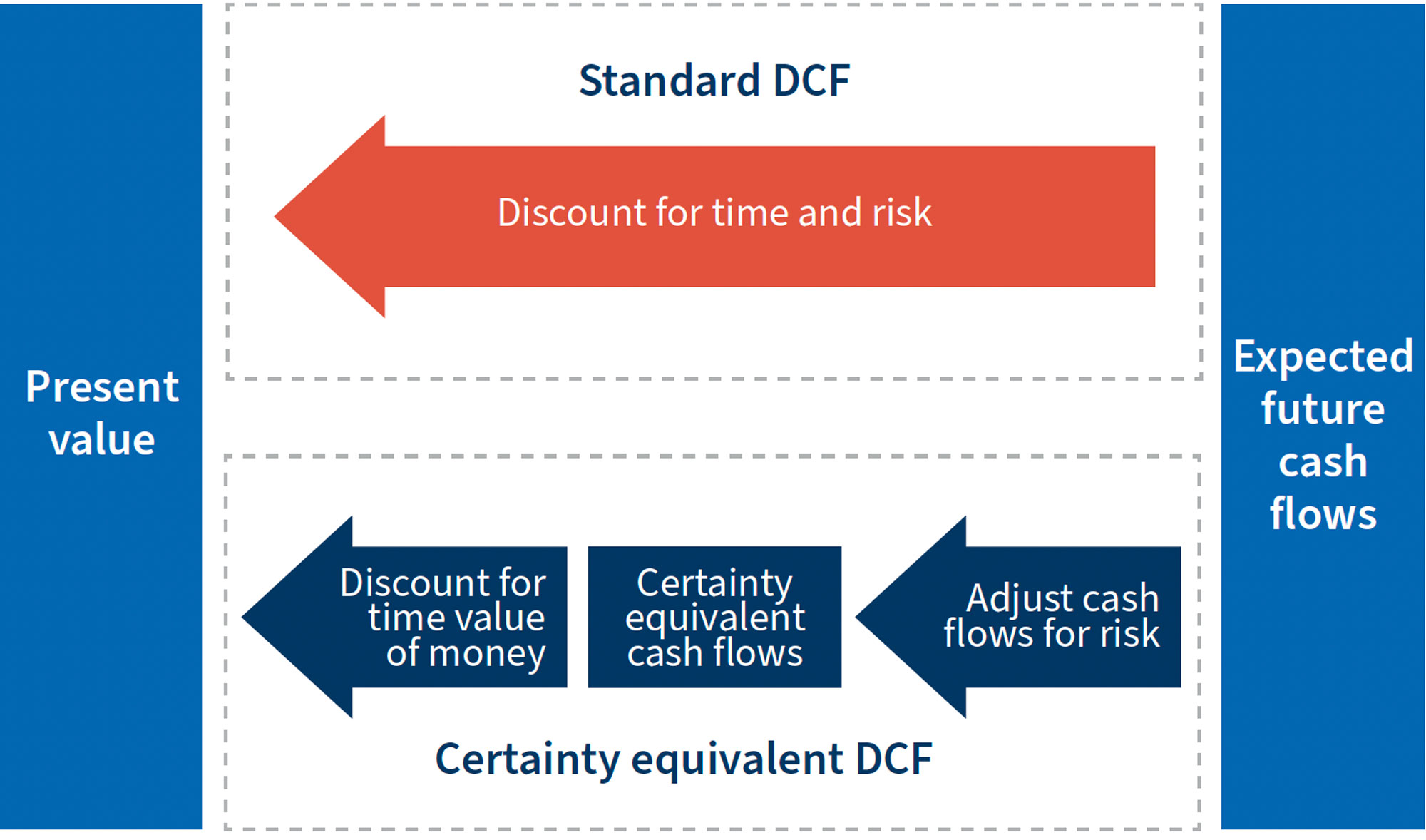

In the most commonly used income approach, the standard DCF approach, the valuer forecasts the expected (that is, probability weighted) future cash flows and discounts these at a risk-adjusted discount rate that reflects both the time value of money (through the risk-free rate) and the systematic risks attached to them (through the incorporation of a risk premium).

An alternative approach is to directly adjust the expected future cash flows for systematic risks and discount these risk-adjusted cash flows at a risk-free rate that reflects only the time value of money. Under this approach, the expected cash flows are replaced with their ‘certainty equivalents’. In terms of financial economics, the concept of a certainty equivalent refers to the certain, risk-free, pay-off that would make a risk-averse investor indifferent between opting for either the certain pay-off or a higher expected pay-off that is subject to risk.2 In other words, this alternative approach is based on the principle that a risk-averse investor would be indifferent between owning the subject asset with its expected cash flows and owning an alternative asset with lower but certain cash flows.

In both cases, the adjustment is made in respect of systematic risks, meaning those risks which cannot be diversified away (for example, some of the oil price risk associated with the value of an oil well cannot be fully diversified away by holding a broad portfolio of assets and, therefore, is a systematic risk). According to financial theory, the market does not compensate investors for taking on risk that can be diversified.

This alternative approach described above goes by various names, including the ‘Modern’ and the ‘certainty equivalent’ DCF – we prefer the latter terminology as it is more descriptive of the approach itself. The term ‘Modern’ DCF is also more open to misinterpretation, considering that, as far as we are aware, this method has been discussed in academic circles since at least the 1960s.3

The term ‘Modern’ DCF is sometimes used to encompass more than just the methodology described above, whereby the subject asset’s expected cash flows are replaced with their certainty equivalents and then discounted at a risk-free rate.

First, the term is sometimes used to encompass the incorporation of an additional concept, real options, into a valuation.4 Real options can be defined as management’s ‘opportunities to modify projects as the future unfolds’.5 As an example of a real option, the manager of an oil well may be able to shut-in (stop) production when oil prices decline and restart production if oil prices subsequently increase. In fact, real options can be used to complement any income approach, including one performed using the standard DCF.6 In other words, the use of real options is not a necessary element of a ‘Modern’ or certainty equivalent DCF, and real options can be used in other contexts.

Second, the term is sometimes used to encompass adjustments made to expected cash flows to account for asymmetric risks.7 An example of an asymmetric risk is the risk of a blowout of an oil well. In fact, asymmetric risks, or indeed any other risks that are not systematic, should be reflected in the expected cash flows under any income approach, including the standard DCF.

Ultimately, the only difference between the ‘Modern’ or certainty equivalent DCF and the standard DCF approaches is in the way they adjust for systematic risks.

Theoretical Appeal of the Certainty Equivalent DCF

According to the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), both the standard DCF and the certainty equivalent DCF can in theory be used to assess the fair value of a project or company.8

To present the theoretical appeal of the certainty equivalent DCF, it can be helpful to consider the arguments presented to the tribunal in Tethyan v Pakistan. In particular, the claimant’s expert, who put forward a valuation based on this approach, argued that the certainty equivalent DCF can resort to ‘very good market signals as to how the market values [systematic] risks’.9 While the claimant also submitted that this method more accurately accounts for asymmetric risks and can incorporate management’s flexibility, we focus on the reference to market signals since, as described above, these other purported benefits are in fact not unique – or necessary – features of the certainty equivalent DCF.

The reference to market signals is to the price of futures contracts. Futures contracts are often cash-settled but can involve a commitment to sell, or purchase, a given number of units of a product at a contractually agreed future date at a certain price. The use of such contracts eliminates the uncertainty in the price at which the predetermined number of units can be sold at the future date. Therefore, the prices of futures contracts could, in theory, allow valuers to rely on market signals to assess certainty equivalent future prices of certain traded commodities. These, in turn, could be used to estimate certainty equivalents of select components of an asset’s net cash flows.

The claimant’s expert in Tethyan v Pakistan also referred to a 2012 letter from the Special Committee of the Canadian Institute of Mining, Metallurgy and Petroleum on the Valuation of Mineral Properties (CIMVal) to the International Valuation Standards Council (IVSC). In this letter, CIMVal explains that its members generally use an income approach ‘where there is sufficient information available to estimate future cash flows generated by a metals-related investment’,10 and describes the standard DCF and the certainty equivalent DCF as two income approaches used to value these investments.

CIMVal points to two reasons a valuer might use the certainty equivalent DCF. First, it allows for the use of targeted risk adjustments for different components of the net cash flows.11 Second, CIMVal considers one reason the certainty equivalent DCF may be used for long-life assets is because it does not assume that risk compounds constantly over time.12 However, academics and CIMVal acknowledge that, in principle, the standard DCF approach can be adjusted to deal with both these issues, if that were to be desired by the valuer.13

Therefore, the main appeal of the certainty equivalent DCF, relative to other income approaches, is that, in theory, it can allow a valuer to rely on market information to adjust expected cash flows for systematic risks. However, what are the practical challenges with achieving this?

Challenges of Implementing the Certainty Equivalent DCF in Practice

Futures contracts are most prevalent in commodity markets. Hence some valuers propose that the certainty equivalent DCF can be used to value commodity assets, including projects in the resource and power sectors.14 In other sectors (for instance, hospitality), such contracts are generally not available to eliminate systematic risks of select cash flow components. Therefore, in the following discussion, we focus on resource projects.

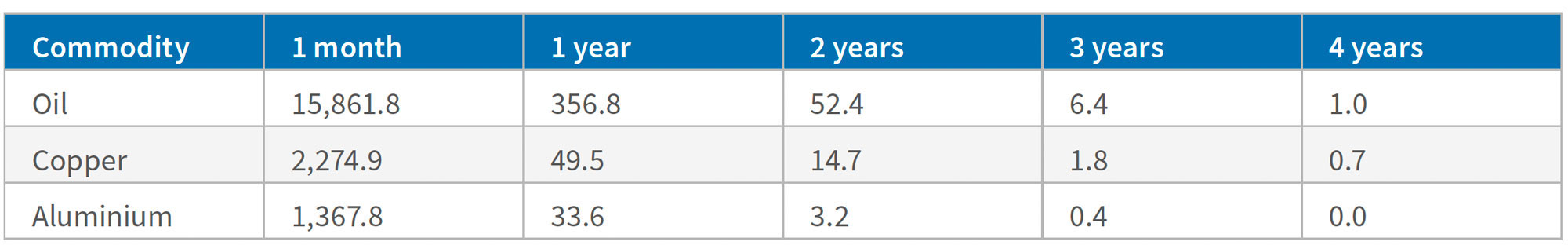

The first challenge with using the certainty equivalent DCF approach is that resource projects typically have a lifespan of several years to a few decades. This can be substantially longer than the maturity of liquid futures contracts. There is often no market, let alone a liquid market, for futures contracts beyond a few initial years. This is illustrated in the table below, which shows the average daily traded value of front month and longer maturity futures contracts for different commodities.

Table 1: Futures contracts, average daily value of contracts traded in 2021/22 ($ million)

Note: Average daily value traded between 1 July 2021 and 30 June 2022. This is based on generic futures contracts expiring in 1 month, 13 months, 25 months, 37 months and 49 months, respectively. Oil is based on futures contracts for Brent oil. Copper and aluminium are based on futures contracts traded on the London Metal Exchange. Source: FTI Consulting analysis of Bloomberg data.

As Table 1 shows, liquidity drops off steeply the further out the maturity of the futures contract. For example, at the date of this exercise, there was limited traded value in futures contracts with expiry beyond three years for oil and copper and beyond two years for aluminium. In addition, in all three commodities analysed, the value of the futures contracts traded with expiry in one year and thereafter was dwarfed by the value of one-month contracts, which some analysts use to assess spot prices. In such illiquid markets, prices may not act as reliable market signals. Further into the future, there is often no market for futures contracts at all.

As a result, valuers using this approach must resort to projecting certainty equivalent prices forward (often for most of the duration of the DCF analysis), for instance by extrapolating from (illiquid) long-term futures and forward prices or by adjusting long-term price forecasts. These forecasts will necessarily involve the valuer’s judgement.

As an illustration of this issue, in Tethyan v Pakistan, the claimant’s expert relied on the forward curve for commodity prices and extrapolated prices beyond this to estimate certainty equivalent cash flows for years extended into the future. The tribunal observed that ‘[i]t is undisputed that there is no market pricing of the systematic risk extending over a 56-year mine life’. To account for this, the tribunal in that case applied a residual risk reduction of 25% to the claimant’s expert’s assessment of the project’s cash flows to adjust for this long-term pricing risk.15

Furthermore, resource projects’ future production and sales volumes are usually uncertain, often highly uncertain in early-stage projects, and these volumes may have a significant systematic risk component. For example, companies may ramp up resource production during periods of high commodity prices and slow down production during periods of low prices. To the extent that there are systematic risk components to forecast future production, a valuer using the certainty equivalent DCF should also adjust expected cash flows for these risks when arriving at the certainty equivalent cash flows.

Another challenge related to relying on futures contracts for commodity prices is that such contracts relate to a particular commodity (of a particular standard) at a particular delivery location. Therefore, there may be a mismatch between the commodity used in the project and that underpinning the futures contract.

However, a much more significant challenge with the implementation of this approach is that, in addition to adjusting cash flows for revenue pricing and volume risk, a valuer using the certainty equivalent DCF needs to adjust the other components of net cash flows for other sources of systematic risk. For instance, resource projects are prone to delays and capital expenditure cost overruns. According to studies,16 73% of large oil and gas projects take longer to complete and 64% of large mining projects suffer cost or schedule overruns – or both. To the extent that there are systematic risk components to any such delays and cost overruns, a valuer using the certainty equivalent DCF should adjust expected cash flows for these risks when arriving at the certainty equivalent cash flows. As an example, initial capital expenditure may include significant labour costs, and those costs may have a systematic component.

A valuer also needs to account for any systematic risks associated with the various components of costs in a resource project. Although futures contracts may exist for some of these components, such as the price of steel, markets for these contracts are also illiquid beyond a few years. For the remaining components, such as labour costs and taxes, futures contract prices are not available. These costs can be substantial and are subject to change, particularly over long periods, and these changes may also have a significant systematic component to them. These cash flow components will need to be adjusted for in arriving at certainty equivalent cash flows, without the possibility of relying on any market signals.

As a result, when estimating certainty equivalent cash flows as part of a certainty equivalent DCF, it is not possible to rely solely on market evidence provided by futures prices. Rather, the valuer will need to make further assumptions which will invariably involve substantial judgement. This is recognised in the CIMVal letter, in which CIMVal states that ‘[a] residual risk adjustment may be necessary to adjust previously risk-adjusted cash flows for risks not explicitly recognized in the model before a final adjustment for the time value of money.’17

Therefore, although the certainty equivalent DCF’s proposition of relying on market signals to adjust expected cash flows for systematic risks is appealing in theory, in practice these market signals are often unavailable for large components of an asset’s expected net cash flows. Adjusting such components to assess their certainty equivalent values typically requires substantial judgement by the valuer, as there is often little or no evidence available of what an appropriate adjustment would be.

The choice of valuation approach is not performed in a vacuum. Rather, valuers will consider what the best valuation approach to apply is, given the evidence available and the specific circumstances that apply to each case. According to the IFRS, whether the certainty equivalent DCF or the standard DCF should be applied ‘will depend on facts and circumstances specific to the asset or liability being measured, the extent to which sufficient data are available and the judgement applied’.18

While the standard DCF also requires judgement by the valuer when assessing the risk premium to apply to the discount rate, the judgement required in this respect is usually to assess how much weight should be put on different pieces of available market evidence. For example, some valuers estimate the equity market risk premium using the historical performance of equity compared to government bonds. Other valuers use current market prices and forecasts to estimate an implied future equity risk premium. The equity market risk premium is then generally multiplied by the ‘beta’, which valuers typically estimate using the correlation between the historical returns on equity of similar companies and the historical returns of the market as a whole, although different valuers may calculate this differently (for example, using different market indexes, time periods and time intervals).

Therefore, the theoretical ability to adjust for systematic risk based on market signals under the certainty equivalent DCF is, in practice, unlikely to constitute a real benefit which reduces the need for valuer judgement in this methodology relative to the judgement required when using the standard DCF approach.

Lack of Use of the Certainty Equivalent DCF by Market Participants

Market value and fair market value are standards of value commonly used in international arbitration. The International Valuation Standards (‘IVS’) define ‘market value’ as ‘the estimated amount for which an asset or liability should exchange on the valuation date between a willing buyer and a willing seller in an arm’s length transaction, after proper marketing and where the parties had each acted knowledgeably, prudently and without compulsion’.19 This is broadly similar to the OECD and US IRS definitions of ‘fair market value’ and the IFRS accounting standards definition of ‘fair value’.20

Market value and fair market value should reflect the price agreed ‘between a willing buyer and a willing seller in an arm’s length transaction’.21 The IVS explain that to assess market value using an income approach, a valuer should use ‘inputs and assumptions that would be adopted by [market] participants’.22 It follows that a relevant factor when evaluating a valuation in the context of an assessment of (fair) market value is whether a valuer’s approach reflects the inputs and assumptions that market participants would adopt in the same circumstances. When this is not the case, it is more likely that the subject valuation may not reflect what willing parties would have agreed to in the market.

A potential drawback of the certainty equivalent DCF approach, when used to assess market value or fair market value, is that it does not appear to be widely used by market participants when valuing companies or projects.

In Tethyan v Pakistan, the claimant’s expert pointed to one transaction in the mining industry in which it was applied.23 However, according to the respondent, this transaction was described in the press as ‘the worst mining deal ever’.24 Therefore, it is not clear that this transaction truly reflected the ‘inputs and assumptions’ normally adopted by market participants. We are not aware of any other transactions in which the certainty equivalent DCF was used in mining or in any other sector.25

In Tethyan v Pakistan, in response to the respondent’s argument that the certainty equivalent DCF is not used in the mining industry, the claimant’s expert referred to the 2012 CIMVal letter26 where CIMVal identifies both the certainty equivalent DCF and the standard DCF as appropriate income approaches to value metals-related investments where sufficient information is available to estimate future cash flows, and discusses why a valuer might use the certainty equivalent DCF. However, in this letter CIMVal does not suggest that this approach is widely used by market participants.27

Additionally, we are not aware of any surveys that discuss the assumptions adopted by market participants in the certainty equivalent DCF, which may reflect that this approach is relatively uncommon.

In our experience, when a market participant has used an income approach to value an asset, this has involved the use of the standard DCF approach. There are also many surveys documenting the assumptions used by valuers and managers when assessing the risk-adjusted discount rate that is used in the standard DCF approach28 illustrating the ‘inputs and assumptions’ that are being adopted in practice by market participants.

The relative use of the standard DCF and certainty equivalent DCF among market participants is reflected in their relative use in arbitration. In the 24 publicly available arbitration awards of damages of more than $100 million recorded on the ‘italaw’ website,29 of the 14 awards that identified the chosen valuation approach, 11 cases used the income approach.30 All 11 of those awards relied on the standard DCF rather than other income approaches.31 Other than Tethyan v Pakistan,32 we are not aware of any case in which the certainty equivalent DCF was relied on in some capacity when awarding damages.

The suitability of different income approaches depends on the available evidence and specific circumstances of each case. The evidence of the limited use of the certainty equivalent DCF by market participants, relative to the standard DCF, suggests that in most cases the specific circumstances and available evidence might better support a standard DCF approach.33 The limited use of the certainty equivalent DCF does not appear to be explained by the purported recency of this methodology, since this approach has co-existed with the standard DCF for around six decades.

Final Thoughts

The main appeal of the certainty equivalent approach is that, in theory, it can allow a valuer to rely on market information to adjust expected cash flows for systematic risks, such that these risk-adjusted cash flows can then be discounted at the risk-free rate. This approach differs from the standard DCF, the most commonly used income approach, in which the systematic risk is accounted for by applying a risk premium to the discount rate, which is then applied to the expected cash flows.

However, this benefit is really only applicable in theory and not reality. In most circumstances, the information that would allow a valuer to rely on market signals to adjust all the components of a project’s or company’s expected net cash flows for systematic risk is usually unavailable or incomplete. As a result, valuers may need to use their judgement to make assumptions for which there is often little or no market evidence. Although valuers applying the standard DCF will also need to rely on judgement to assess the appropriate risk premium, that judgement will usually involve deciding what weight should be applied to several different pieces of available market data.

Standards of value commonly used in damages assessments in arbitration, such as fair market value and fair value, explain that the valuation approach should reflect the inputs and assumptions that would be adopted by market participants. This may be problematic for the certainty equivalent DCF approach because this method does not appear to be commonly used by market participants to value companies or projects. It may be difficult, therefore, to assess whether the certainty equivalent assumptions used by a valuer would in fact reflect those of market participants. Despite co-existing with the certainty equivalent DCF for around six decades, the standard DCF remains much more commonly used by market participants, including in the industries that are in theory well suited to the application of the certainty equivalent DCF – namely oil and gas, mining and power.

Case Study

The Tethyan v Pakistan award, in which the tribunal awarded $4.1 billion in damages,34 arose from a dispute between Pakistan and Tethyan, an Australian mining company, in relation to a mining licence application by Tethyan.35

The tribunal in this matter expressed a preference for an income approach, stating ‘the Tribunal is convinced that in the particular circumstances of this case, it is appropriate . . . to determine [the claimant’s] future profits by using a DCF method’.36

The claimant’s expert used a certainty equivalent DCF to assess damages.37 The tribunal observed that it had ‘not been provided with a traditional [standard] DCF calculation by either Party, or any other income-based calculation’ besides the claimant’s expert’s certainty equivalent DCF.38 The tribunal therefore had to decide whether to rely on the claimant’s expert’s certainty equivalent DCF or to use an alternative to the income approach.

The tribunal decided to rely on the certainty equivalent DCF prepared by the claimant’s expert. However, the tribunal introduced further ‘residual risk adjustments’ to the certainty equivalent cash flows for systematic risks, which it considered had not been ‘fully captured in the available market data’ and the extrapolation of such data.39 In particular, the tribunal concluded that ‘it is likely that a buyer would have assigned a price to assuming this long-term risk by reducing its expectation of the cash flows’. The tribunal therefore reduced the cash flows assessed by the claimant’s expert by 25%, leading to a reduction in value of $2,430 million (about 60% of the tribunal’s pre-interest award of $4,087 million).40

The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and not necessarily the views of FTI Consulting, Inc., its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, or its other professionals. FTI Consulting, Inc., including its subsidiaries and affiliates, is a consulting firm and is not a certified public accounting firm or a law firm.

Footnotes:

1: International Valuation Standards Council (IVSC), IVS 105: 40.1.

2: For instance, an investor might be indifferent between receiving $30 with certainty and receiving an uncertain pay-off that can be either $0 or $100 with equal probability. In this example, $30 would be the certainty equivalent of the risky cash flow with expected pay-ofof $50 ($0 * 50% + $100 * 50% = $50). The exact value or discount of the certainty equivalent will depend on the investor’s degree of risk aversion

3: For example, in Alexander A Robichek and Stewart C Myers, ‘Conceptual problems in the use of risk-adjusted discount rates’ in The Journal of Finance, Volume 21, Issue 4 (December 1966), at 727–30.

4: For instance, the claimant in Tethyan v Pakistan submitted that the ‘Modern’ DCF “incorporates management’s flexibility to choose different options in response to evolving circumstances.” Tethyan v Pakistan Award, at 224.

5: Richard A Brealey, Stewart C Myers and Franklin Allen, ‘Principles of Corporate Finance’, Chapter 10 (tenth edition, 2010), at 240.

6: For instance, Van Putten and MacMillan state that “it seems clear to us that discounted cash flow analysis and real options are complementary and that a project’s total value is the sum of their values. The DCF valuation captures a base estimate of value; the option valuation adds in the impact of the positive potential uncertainty.” See Alexander B van Putten and Ian MacMillan, ‘Making Real Options Really Work’, Harvard Business Review (December 2004).

7: For instance, the claimant in Tethyan v Pakistan submitted that “[t]he modern DCF method more accurately discounts future cash flows for … asymmetric risks’.”TethyanvPakistan Award, at 224.

8: International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) 13, at B29.

9: Tethyanv Pakistan Award, at 346.

10: Letter to IVSC on behalf of CIMVal (Special Committee on the Valuation of Mineral Properties at the Canadian Institute of Mining, Metallurgy and Petroleum), 22 October 2012, available at https://paperzz.com/doc/7603199/012-cimval---international-valuation-standards-council (last accessed 18 October 2022).

11: CIMVal states: “A CeQ [certainty equivalent] DCF approach does not make use of an aggregate discount rate though an implied aggregate discount rate can be derived. The CeQ approach uses targeted risk-adjustments for select cash flow components. These adjustments are done within the CAPM [capital asset pricing model] framework. Market-related uncertainties such as metal and energy prices are risk-adjusted with the CAPM while project-specific uncertainties may be modelled directly with no risk-adjustment. A residual risk adjustment may be necessary to adjust previously risk-adjusted cash flows for risk not explicitly recognized in the model before a final adjustment for the time value of money.” Letter to IVSC.

12: CIMVal states: “A by-product of using the CeQ [certainty equivalent] DCF method is that [the] effective aggregate discount rate implied by this analysis can change with the variation of cash flow uncertainty as a result of changes in operating leverage and other project characteristics. This may be one reason that this approach is used.” Letter to IVSC.

13: In a standard DCF, different discount rates can in principle be used for different cash flows or time periods, although this is rarely done by market participants in practice. In response to the question ‘Do you use multiple discount rates to reflect the changing risk profile as an extractive process moves through its life cycle?’, CIMVal states: “Sometimes. For example, in cases where a static DCF [standard DCF] is being used, higher discount rates may be applied to reflect uncertainties not related to time (such as applying higher discount rates to more geologically uncertain resources).” Letter to IVSC. Brealey, Myers and Allen at 233 state that ‘where risk clearly does not increase steadily’, one should either ‘break the project into segments within which the same [risk-adjusted] discount rate can be reasonably used’ or ‘use the certainty-equivalent version of the DCF model’.

14: For instance, CIMVal stated in its 2012 letter that the certainty equivalent DCF “is used for select types of real assets such as natural resource projects.”

15: Specifically, the tribunal stated: 'It is undisputed that there is no market pricing of the systematic risk extending over a 56-year mine life and Prof. Davis specifically agreed at the Hearing on Quantum that the cash flows acquired by the buyer would remain “highly uncertain and highly risky.” The Tribunal therefore concludes that it is likely that a buyer would have assigned a price to assuming this long-term risk by reducing its expectation of the cash flows that the Reko Diq project would generate over the life of the mine by 25%. This results in a reduction of the value of Claimant’s investment by USD 2,430 million.’ Tethyanv Pakistan Award, at 1425, 1440, 1441, 1521 and 1596.

16: ‘Spotlight on oil and gas megaprojects’, EY, 2014. ‘How better project management can boost mining’s capital productivity’, EY, 2022.

17: Letter to IVSC

18: IFRS 13, at B30.

19: IVS 104 Bases of Value, IVSC, at 30.1.

20: The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development defines ‘fair market value’ as ‘the price a willing buyer would pay a willing seller in a transaction on the open market’ while the US Internal Revenue Service defines it as ‘the price at which the property would change hands between a willing buyer and a willing seller, neither being under compulsion to buy or sell and both having reasonable knowledge of relevant facts’. IFRS 13 explains the ‘fair value’ of an asset or liability ‘is a market-based measurement’, namely ‘the price at which an orderly transaction to sell the asset or to transfer the liability would take place between market participants at the measurement date under current market conditions’. IVS 104 Bases of Value, IVSC, at 30.1, 100.1, 110.1; and IFRS 13, at 2.

21: IVS 104 Bases of Value, IVSC, at 30.1.

22: IVS 104 Bases of Value, IVSC, at 30.5.

23: Tethyan v Pakistan Award, at 254.

24:Ibid, at 254.

25: This includes the experience of one of the authors at various investment banks (between 1994 and 2015, Stuart Amor worked at Credit Suisse, ING, UniCredit and RFC Ambrian) as either an equity analyst covering the oil and gas industry or as a global head of research overseeing the bank’s coverage of all sectors, including mining.

26: TethyanvPakistan Award, at 347.

27: In its ‘Standards and Guidelines for Valuation of Mineral Properties’, dated February 2003, CIMVal comments that the certainty equivalent DCF was “[n]ot widely used and not widely understood but gaining in acceptance.” CIMVal refers to the certainty equivalent DCF as an ‘Option Pricing’ income approach; available at https://mrmr.cim.org/media/1020/ cimval-standards-guidelines.pdf (last accessed 18 October 2022).

28: For instance, Professor Pablo Fernandez regularly conducts surveys of the risk-free rate and equity risk premium used by analysts, managers of companies and finance and economics professors. For example, see Survey: market risk premium and risk-free rate used for 95 countries in 2022, Fernandez et al, 24 May 2022.

29: We used the filter on the italaw website (https://www.italaw.com/) to identify all awards for which damages of more than $100 million were recorded. Research conducted around Q3 2022.

30: Some of these 11 awards combined the income approach with other approaches. For instance, in ICSID Case No. ARB/13/1, the tribunal relied on the income approach for some heads of claim and the cost approach for others. In the remaining three awards where the tribunal did not rely on an income approach, the tribunal instead used a market (comparable) approach, a cost approach and a combination of a market approach and a cost approach.

31: Based on our review, the tribunal relied on a standard DCF approach in the awards in the following 11 cases: SCC Case No. V 2014/163; ICC Case No. 20549/ASM/JPA (C-20550/ASM); ICSID Cases No. ARB(AF)/09/1, No. ARB/13/1, No. ARB/08/6, No. ARB/13/36, No. ARB/13/31, No. ARB/11/25, No. ARB/07/27 and No. ARB/15/44; and MCCI Case No. A-2013/29.

32: The Tethyan v Pakistan award was not included in the results of our italaw search described above as its damages were not recorded on the italaw website.

33: The limited use of the certainty equivalent DCF relative to the standard DCF might also be related to the complexities involved in estimating certainty equivalent cash flows as discussed above. For instance, Professor Damodaran explains that estimating a discount rate using risk and return models such as CAPM is “a convenient way of adjusting for risk and it is no surprise that they are in the toolboxes of most analysts who deal with risky investments.” Regarding the estimation of certainty equivalent cash flows, he explains that the practical challenges of doing so remain ‘daunting’. Damodaran, ‘Risk adjusted value’, at page 5 and 10.

34: Tethyanv Pakistan Award, at 1601, 1858.

35: Ibid, at 86.

36: Ibid, at 335.

37: Ibid, at 336.

38: Ibid, at 1651

39: Ibid , at 1521

40: Ibid, at 1600 and 1601.

Published

December 05, 2024

Key Contacts

Key Contacts

Senior Managing Director

Managing Director

Senior Director

Downloads

Most Popular Insights

- Beyond Cost Metrics: Recognizing the True Value of Nuclear Energy

- Finally, Pundits Are Talking About Rising Consumer Loan Delinquencies

- A New Era of Medicaid Reform

- Turning Vision and Strategy Into Action: The Role of Operating Model Design

- The Hidden Risk for Data Centers That No One is Talking About