- Home

- / Insights

- / Whitepapers

- / The 2022 Australian Federal Election

The 2022 Australian Federal Election

-

April 13, 2022

DownloadsDownload Whitepaper

-

On 21 May 2022, the Australian electorate will go to the polls in what most expect to be one of the hardest fought and most contentious elections during a time when contentious elections have become the norm. To help business navigate this unpredictable landscape, FTI Consulting lays out the path to the election, the various scenarios that could arise, and highlights implications for business.

Introduction – Certainty and Uncertainty

Along with the rest of the world, Australia has had to contend with the changing phases of the COVID-19 pandemic over the last three years. The public health challenge soon became a global lockdown and, while Australia initially fared better than some of its contemporaries, the challenges of administering the vaccine rollout and responding to the Delta and Omicron variants has put enormous pressure on the Australian Government.

The crisis in Ukraine remains a major geopolitical issue for the Government and also continues to put pressure on the cost of living, fuel prices, and supply chains for Australians.

On top of these global issues, Australia has also faced devastating floods in 2022, and months of catastrophic bushfires through the summer of 2019 and 2020. Prime Minister Scott Morrison MP and the Liberal National Coalition have also failed to pass a number of key legislative commitments 1, while concurrently defending itself against intense political attacks – from both outside the Government and within - on a range of high-profile social issues.

It has clearly been a turbulent and testing term and, if the content and reaction to the recent handing down of the Federal Budget is any indication,2, 3 the coming election is likely to be the culmination of one of the hardest-fought and contentious campaigns in recent years.

The result4 is likely to come down to voting in a small number of marginal seats across the country. While the Coalition is in a difficult position, currently holding only a one-seat majority, it has often been easier for an incumbent to hold what they have, rather than an opposition try to gain government.

Broadly, most agree there are four possible outcomes, a victory by either the Coalition or the Australian Labor Party, or a minority government formed by either side with the support of independents. The importance of smaller parties and independent candidates has increased significantly and may well dictate the outcome of this election.

With the election looming, we want to provide some information on the possibilities and potential outcomes and what business can do to navigate this uncertain landscape.

Put simply, Australia’s new policy and regulatory regime for the next three years will be decided in May - if the Coalition wins outright, it will be business as usual. If they depend on independents in a minority government, the independents will hold sway over policy and regulation.

If Labor wins (or a Labor Minority Government occurs), there will be a substantial shift in policy and regulation. It will be critical for business, especially those in heavily regulated sectors, to be agile and adjust business plans to respond to the impact of new policy.

In these unprecedented times, it might seem like the only certainty is uncertainty, but we can explore the implications of the upcoming election and how best to prepare for what comes next.

The Australian System – Setting the Scene

Under the Australian Constitution, elections for the House of Representatives must be held at least every three years; the Prime Minister decides the exact date.

Each House member is elected using a system of preferential voting that is designed to elect a single member with an absolute majority at the end of the process.

Under the preferential voting system:

- Voters write a number in the box beside every name on the ballot-paper in a ranked order.

- If a candidate gains an absolute majority of first preference votes, they win the seat.

- If no candidate receives an absolute majority, the candidate with the least number of votes is excluded and their votes are redistributed according to second preferences

- This process of redistribution continues until one candidate receives more than 50 per cent of the vote.

The preferences of seemingly minor candidates who are knocked out early in the count can therefore be very important.

Following the election, the Australian Government is formed by the party or coalition with a majority in the House. The Prime Minister is the parliamentary leader who has the support of a majority of members in the House.

As government is determined by having control of the majority of seats in the House, it is important to understand that it is the number of seats that determines who wins an election and not who wins the cumulative number of votes at a national level.

This is why any national polling5 that measures ‘two party preferred’ voting intention is only really a measure of overall voter sentiment. There are many historical examples of situations where a government has been formed with less than 50 percent of the overall vote but with a majority of seats in the House. Consequently, political parties and professional pollsters pay significant attention to marginal seats because that is where the contest for government can be won or lost.

The Australian Federal System

- Australia is a Constitutional Monarchy and part of the UK Commonwealth.

- It is a federation comprising of a national government, six states and two self-governing territories (each with their own parliaments, governments and laws), underpinned by the Constitution of Australia.

- It is a representative Westminster-style, parliamentary democracy with three separate arms: Parliament, Executive and Judiciary.

- The Australian Parliament is located in Canberra and comprises two chambers: the House of Representatives and the Senate.

- The House is comprised of 151 members6 who each represent one geographic area of Australia. On average, 150 000 people live in each electorate, with an average of 105 000 voters. Members are elected for a 3-year term.

- The Senate is comprised of 76 senators, twelve from each of the six states and two from each of the mainland territories.

- Senators are elected for six years so, generally, half of the Senate is up for election every three years, when the House is up for election.

- Legislation must pass both the House of Representatives and the Senate to become law in Australia.

- Australia has a compulsory voting system and all Australians over 18 years must vote on election day in person or by post.

The composition of the Senate and the ability to manage the Senate, is also crucial to the agenda of any government. Few modern Australian governments have enjoyed a majority in both Houses. The ability to negotiate legislation through the Parliament is often down to a few key individual Senators with specific agendas.

The Main Players – an Increasingly Complex Picture

The main parties contesting this election in the House are: the Coalition (Liberal and National Parties), the Australian Labor Party (ALP), the Greens, Katter’s Australian Party, the Centre Alliance, the United Australia Party, and a range of independent candidates.

In the Senate, it is a more complicated picture, with dozens of single-issue parties and candidates hoping to gather enough preferences to gain important sway by having an influence on the balance of power. These parties cover the gamut of issues, from environmental concerns to immigration and nationalist reform.

Predicting an outcome is very difficult especially in this unprecedented period of uncertainty. In recent state elections, the pandemic favoured incumbents in Queensland, Tasmania, Australian Capital Territory, Northern Territory and Western Australia. In the most recent election in South Australia, however, the Labor Party claimed a decisive victory over the incumbent Liberal Party government which illustrates that the advantages of incumbency cannot be taken for granted7.

Existing uncertainty has been compounded by the recent unreliability of political polling. In Australia the main issue has been a failure in methodology. Each poll asks the question, ‘If an election was held today. who would you give your first preference to?’ with the possible answers including ‘The Coalition’, ‘the ALP’, ‘The Greens’, ‘Undecided’ and some version of ‘Other parties or independents’. A formula is then used to calculate preference flows and determine which of the two main parties will receive the highest two-party preferred vote. In previous years, pollsters split the ‘undecided’ using a mathematical formula along the same lines as the rest of the population. That is, if the ALP received 52% of the two party preferred vote in the poll, apart from the undecided votes, and the Coalition received 48% of the two party preferred, apart from the undecided votes, then those undecided votes would also be split 52/48.

In 2016, that formula didn’t work. The polls leading up to the election recorded the ALP at 52% and the Coalition at 48%, but the undecided voters didn’t behave as the pollsters predicted. Instead, they actually voted in greater numbers for the Coalition, giving them a narrow victory. The pollsters are sure they have fixed the mistakes in their formulas and are more confident in their ability to predict the outcome in 2022; of course, that remains to be seen.

Colouring the situation further are the more than 30 Voices candidates that have emerged. They are a loosely-related group of independent candidates who are running on the basis of dissatisfaction with the platforms of the major parties. In recent times, they have stood for greater action on climate change, maintaining funding for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, and increased government integrity, tapping into liberal voters who are unlikely to vote Labor, but might consider a credible, ‘small-l’ liberal independent candidate. They believe that action on these issues is being stymied by conservative elements within the two parties.

Perhaps half-a-dozen have a chance of winning their seats. Given a scenario in which neither major party wins enough seats to govern outright is a real possibility, successful Voices candidates may find themselves at the centre of negotiations around forming a minority government with the ALP or Coalition.

If nothing else, they will prompt the Coalition to defend seats they have traditionally taken for granted, which means they’ll have to divert resources from defending other seats or winning new ones.

Clive Palmer and the United Australia Party (UAP) are also increasing their profile. The party spent more than $50 million in the lead-up to the 2019 election and, as is the case today, this advertising was aimed against both the ALP and the Coalition at the start of the campaign, the UAP is expected to increasingly target Labor now that the election campaign has officially begun.

The UAP is tapping into the groundswell of right-wing populist opposition to COVID-19 public health measures – lockdowns, mask requirements, and vaccine mandates – that has been rising in Australia and across many other countries during the pandemic. The re-election of various state governments during the pandemic suggests the audience for Palmer and the UAP may not be large, but based on his advertising spend alone, it is certain that Palmer will have an impact. It is possible the UAP could stymie the ALP’s targeting of conservative-leaning electorates, thereby bolstering the possibility of a minority government, as well as the likelihood of the UAP gaining a seat in the Senate.

Similarly, albeit with less of a national profile, Katter’s Australian Party and the Centre Alliance will continue to have a say in the composition of the Senate, and further complicate things for the major parties on preferences in key seats.

Scenarios and Outcomes - Implications for Business

Navigating the election period will be a challenge, but there are some indicators that may make it easier.

The last Federal Budget8 before the election was handed down on 29 March. With the budget so close to the election, it provided an indication of the Government’s priorities leading into the election campaign.

“Obviously, I’m focusing on winning the next election. But I’m very proud of the fact that Australia’s economic recovery now leads the world9” — Treasurer The Hon Josh Frydenberg MP

Compounded by the impacts of the pandemic and the conflict in Ukraine, Australians are struggling with the sudden rise in the cost of living with record high fuel prices and increases in the weekly grocery bill for families.

As widely predicted, the budget was squarely aimed at delivering a short-term boost to families and middle-income earners in what has been described as a springboard into an election campaign with relief for petrol prices, a tax break for lower income workers and one-off payments for those on welfare.

The Government has pledged to increase10 defence spending, promising a $10 billion boost over the next decade in the area of cybersecurity as well as increasing the numbers of those in uniform.

There was a considerable boost11 for business in the region with $7.1 billion allocated to establish strategic investment hubs in the Northern Territory, north and central Queensland, the Pilbara and the Hunter – these areas will be key in the election outcome.

Campaign Golden Rules

- Avoid being a backdrop during the campaign: political parties have long memories.

- Adjust the timing of business announcements: this will avoid political fallout before and during the election campaign.

- Avoid being captured by party announcements during factory visits: unless there is a specific strategy and need for this.

- Don’t pick winners: you may end up at the wrong post-election party!

There was also support12 for businesses that employ apprentices with $2.8 billion added to the more than $5 billion delivered to trades and apprentices since the beginning of the pandemic.

As the election campaign begins in earnest, however, business should recognise that it provides both opportunity and risk. It is critical that any business is not seen to take sides which is especially important in an election cycle like this one. Businesses should watch for election campaign announcements and explore the implications then, where possible, look to their industry association to advocate on their behalf on these key policy issues in party election statements and platforms.

It is important for business to know which electorates their business footprint extends to and to understand how campaign commitments might have a direct and local impact. This is especially important as the upcoming campaign will likely coalesce around a small number of marginal seats. The outcomes in these seats – especially those in rural and regional areas – will be critical, no more so than if an independent wins and finds themselves in a balance of power position.

Making election predictions is always fraught, not least in a period of enormous uncertainty, but it is worth highlighting that for the second time in Australian federal politics there is a real possibility of a minority government.

If a minority government is formed by either party, they may have a difficult time governing. However, if the experience of the Gillard Government (the only other federal minority government in Australia’s history since the Second World War) and the current Trudeauled Government in Canada are any guide, a minority government can still execute a significant policy agenda – how they go about it is crucial.

The key to engaging with a minority government revolves around compromise, building relationships, and pursuing a consistent agenda. A minority government creates the need to prioritise wider consultation with backbenchers and independents, meaning that MPs have more input into the policy agenda. This creates opportunities to work within the system to bring matters to national prominence. To be successful, the Government must concentrate on building relationships through the parliament and compromise on individual issues in pursuit of their overall strategy.

Additionally, business should guard against a sole focus on results in the House. The Senate will be critical for the passing of legislation as the Government will need to work much more closely with minor parties to reach agreement. Business, especially Government Business Enterprises, will need to watch for Senate Committees and inquiries in new term to look for opportunities but also to identify where they might be in the Government’s sights.

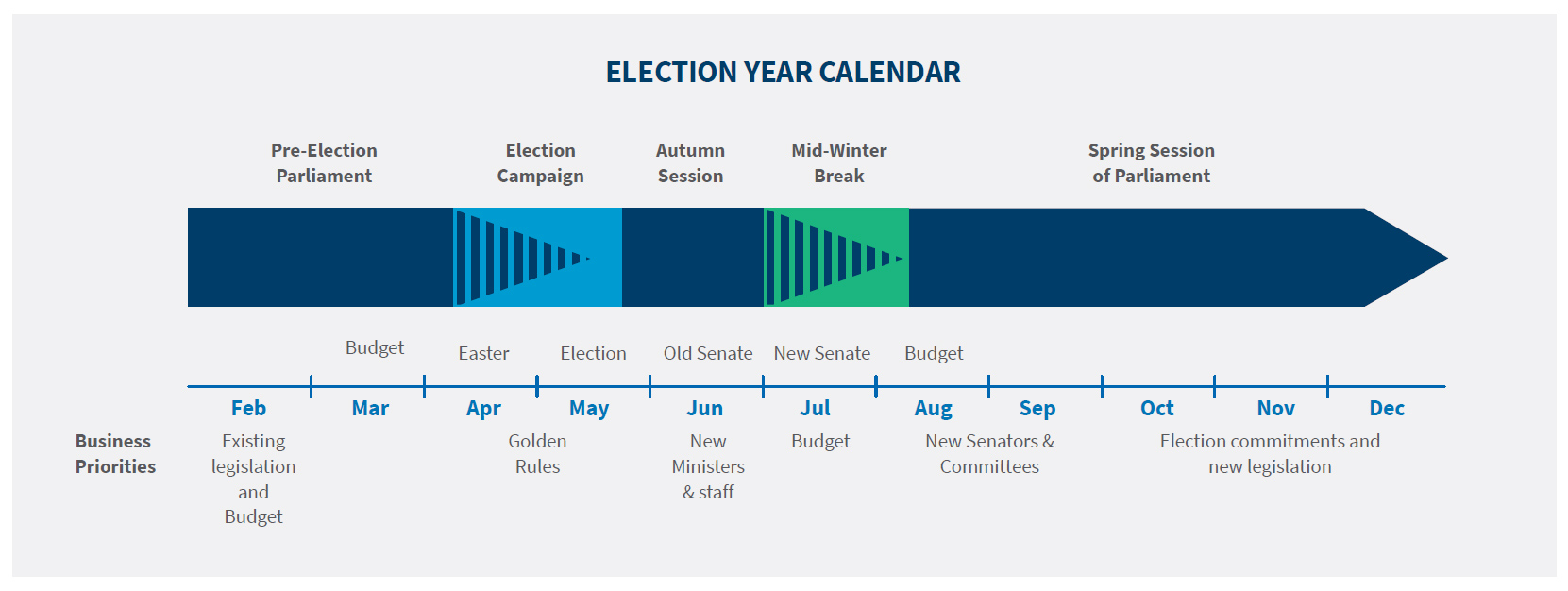

With such a short election campaign and then a short Parliamentary sitting before the mid-Winter break, the best time to engage with Ministers will be in their electorate during the break. There will be a mini-budget or another August budget after the election, especially if Labor wins. The Spring session will focus on implementing election commitments, so this is the time to get business proposals into the policy mix. Watch out for new Senate Committees and inquiries driven by Independents.

This period of greater access to the policy agenda is a real opportunity for business but, on the other hand, a minority government might also result in the major parties remaining on a campaign footing. This will mean they will spend the term of government trying to win points towards the next election where they would aim to win an outright majority. Finding a path to engage with government in a meaningful way through this turbulence would likely prove a challenge.

Regardless of the outcome of the election or the make-up of the parliament, there are some things that won’t change and some challenges that any incoming government will have to contend with.

The pandemic is not over and remains a concern while cost of living – despite the short term relief afforded by the budget measures announced on 29 March – will continue to be a bigger issue for voters this year.

While the Australian economy has weathered the effects of the Omicron variants reasonably well, with global ratings agency S&P reaffirming Australia’s AAA credit in January based on an ‘improving’ fiscal outlook, the effects of the crisis in Ukraine on fuel prices and supply chains will continue to have a big impact on Australians.

Even with the cost of living measures announced, a tax cut designed to boost consumer spending is expected, regardless of the election outcome. The next government will have to look to restrict spending in 2023 to address Australia’s large Budget deficit. Further tax reform will be on the agenda if a return to more robust levels of growth and record iron ore exports do not continue.

While the establishing of a National Cabinet as a forum for the Prime Minister, Premiers and Chief Ministers to meet and work collaboratively through the pandemic has been a necessary and, overall, beneficial measure over the last two years, it has also brought into sharper focus the tensions between the Federal Government and the States. As Australia navigates the next phase of the pandemic, and plans for a sustained, long-term recovery, these tensions and differences will likely increase. How an incoming government approaches this relationship will be crucial in preventing National Cabinet from becoming just an added layer of debate and an inhibitor of national business.

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission will have a new Chair – lawyer Gina Cass-Gottlieb – who is widely expected to have a greater focus on enforcement over policy. For business, this means that compliance will be high on the agenda.

The Australian Government will continue to closely watch foreign investment proposals, especially by China and in key sectors, such as logistics and technology. Australia’s Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) - which examines foreign investment proposals for national security and national interest implications – has said it will be assessing applications with the protection of sensitive Australian data as a priority.

While the FIRB process will remain an important check for business, the recent announcement of greater cooperation between Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States through the AUKUS agreement has the potential to provide a significant increase in foreign investment in Australian businesses, predominantly from the United States. The agreement will help deepen cooperation and investment between the countries, specifically in the sectors of cyber, artificial intelligence, quantum technologies, aerospace, resources, and manufacturing. AUKUS will be a big priority for the next government as it sets out to turn intentions into tangible outcomes for Australian businesses, workers, and the economy.

Finally, there are policy issues that have remained unresolved in this current term, including calls to establish a federal independent corruption commission, the fate of the stalled Religious Discrimination Bill, the fulfillment of the Indigenous Voice to Parliament plan, and increasing pressure for faster and more comprehensive action on climate change.

There will be renewed pressure to deal with these hangover contentious issues swiftly so they do not dominate the next term and, if a number of independent Voices candidates are elected, the focus will be acute, along with renewed campaigning for equal pay and attention to issues of gender.

Conclusion

If the last decade in global government, politics, and elections has shown anything, it is that predicting what might happen on 21 May is difficult to say the least. Businesses can ensure they are prepared and able to navigate uncertainty, however.

Indeed, the outcome of the South Australian State Election has illustrated that, in Australia, incumbency should not be taken for granted and that the electorate does not appear to fear change.

At the end of it all, no matter the outcome of the election, there are some things that won’t change over the next three years.

Australia will still be contending with the impacts of the global pandemic, and the Government – whether new or returned – will prioritise continued economic rationalisation and budget repair.

Cost of living issues, especially as regards fuel prices, will remain front of mind for Australians as the effects of the Ukraine crisis continue to be felt.

While all four outcomes remain a possibility, it is highly likely that the next government will need to compromise and seek ever closer relationships across the parliament, with stakeholders, and business if it is to realise its agenda.

This will provide fertile ground for businesses that can align with the central focus of the new government.

Footnotes:

1: Morrison’s three key laws still in limbo as Parliament ends”, The New Daily, 2/12/21, https://thenewdaily.com.au/news/2021/12/02/morrison-key-laws-parliament

2: Budget in the black with voters but not like 2019: Poll”, AFR, 4/04/22, https://www.afr.com/politics/federal/budget-in-the-black-with-voters-but-not-like-2019-poll-20220403-p5aaeg

3: Coalition splashes $8.6 billion on election pitch to voters”, SMH, 29/03/22, https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/put-it-on-the-tab-coalition-splashes-8-6b-on-pitch-tovoters-20220322-p5a6x6.html

4: Australian federal election: the seats that may decide the poll”, The Guardian Australia, 5/12/2021, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/dec/05/australian-federal-election-the-seatsthat-may-decide-the-poll

5: “NewsPoll”, The Australian, accessed 5/04/22, https://www.theaustralian.com.au/nation/newspoll

6: About the House of Representatives”, Parliament of Australia, https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/House_of_Representatives/About_the_House_of_Representatives

7: “Steven Marshall’s Timing Problem”, The Australian Financial Review, 18/03/22, https://www.afr.com/politics/steven-marshall-s-timing-problem-20220318-p5a5zv

8: “Budget documents», https://budget.gov.au/2022-23/content/documents.htm

9: “Practical and temporary’: Frydenberg’s budget pitch to voters”, The Australian Financial Review, 29/03/22, https://www.afr.com/politics/federal/cash-splash-pours-billions-into-must-win-seats-20220328-p5a8pf

10: “Budget 2022-23 delivers record investment in Defence and supporting our veterans”, Department of Defence, 29/03/2022, https://www.minister.defence.gov.au/minister/peter-dutton/media-releases/budget-2022-23-delivers-record-investment-defence-and

11: ”Federal Budget 2022-23 Key Policies at a Glance”, William Buck, 29/03/22, https://williambuck.com/news/business/general/federal-budget-2022-23-key-policies-at-a-glance/#:~:text=The%20Government%20is%20investing%20%247.1,manufacturing%20hubs%20in%20these%20regions

12: “Budget 2022-23”, Budget.gov.au, 29/03/22 https://budget.gov.au/2022-23/content/download/glossy_jobs.pdf, p.10

Published

April 13, 2022