Why Are Financial Markets Ignoring Recession and Stagflation Risk?

-

April 21, 2022

DownloadsDownload Article

-

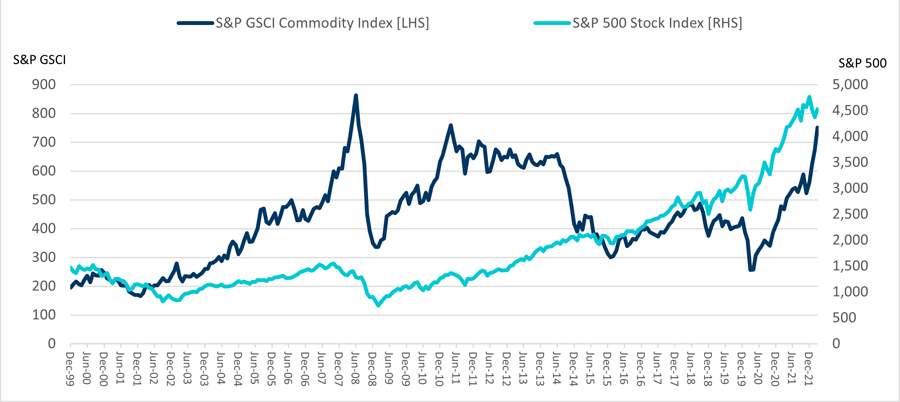

Last month we commented that consumer-level inflation had accelerated to an unacceptably high rate but wasn’t quite as bad as headlines suggested. However, a lot has happened in one short month, mainly a vicious war in Ukraine that has caused prices to soar across the global commodities complex. This spike in prices extends well beyond the grain and energy commodities directly impacted by the war and subsequent sanctions imposed on Russia. Industrial metals, fertilizers, pulp & paper products, construction materials, plastics & resins, and other petroleum-derived chemicals have seen appreciable market price increases since February. The S&P GSCI Global Commodity Index jumped 12% in March, 34% since year end and 61% year-over-year (Exhibit 1). The only time this century that the S&P GSCI Commodity Index was higher than it was in late March was in June 2008, when crude oil prices topped $140 per barrel.

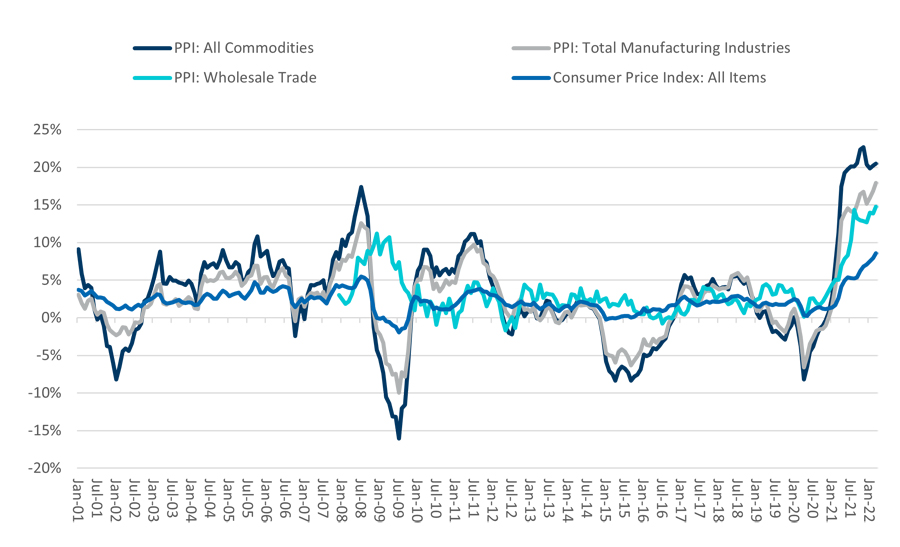

Heavy speculation and profiteering surely have contributed to recent commodity price surges, but the war in Ukraine and the related Russian sanctions threaten to disrupt the supply of certain key global commodities for months to come, further exacerbating an inflation problem already underway and potentially dampening global demand. These price increases already are hitting producers’ costs but haven’t fully worked their way into final product prices (Exhibit 2), which strongly implies that inflation for consumers and other end users will worsen in the months ahead. Most economists believe that inflation will worsen before it begins to moderate, while consumer sentiment dropped to an 11-year low in March primarily because of inflation concerns.

Furthermore, comments from Federal Reserve (Fed) Chairman Powell in March hinted at six more rate hikes this year while the likelihood of a couple of 50 bps hikes has also increased, with several Federal Open Market Committee members indicating support for larger hikes to address inflation more aggressively1. Consequently, 10-year Treasuries have topped 2.75% for the first time since 2019 while mortgage rates have soared to 5.0% within a few months. The Fed is challenged with the tall order of cooling off an overheated economy without snuffing out the recovery. The uncertainty around the duration of war-related inflation spikes and their negative impact on aggregate demand will complicate the Fed’s task. These conditions have the ingredients of a demand-killing recession, or worse, stagflation — a prolonged period of stagnant economic growth coupled with high inflation — should they persist into the second-half of the year. Economists at Goldman Sachs and others have recently put the odds of a U.S. recession in 2023 as high as 35%, well above a normal mid-cycle probability of a downturn2. So why are U.S. financial markets seemingly ignoring these growing economic threats?

Markets are signaling they don’t expect inflation spikes to persist, though reasons for such optimism aren’t obvious or compelling. Domestically, the yield difference between 10-year inflation-indexed Treasury yield and nominal yield implies an inflation expectation of 3.0%, far lower than any inflation gauge currently is running, while market yields on speculative grade bonds have increased by 200-250 bps since year end, a relatively modest uptick compared to the inflation surge. Most economists expect that U.S. inflation will ease towards 5.0% by year end, with some pundits even forecasting inflation as low as 3.0%-4.0% by the end of 2022 despite the added inflation risk posed by the Ukraine war3. In equity markets, the S&P 500 and DJIA have recouped more than half their losses after entering correction territory shortly after the Russian invasion of Ukraine began, and currently are less than 5.0% off their all-time highs despite global turmoil to date. This too shall pass — the mantra of financial markets in times of economic adversity for several years running — remains the prevailing market sentiment, though the Fed doesn’t have investors’ backs this time.

The war in Ukraine and its wider fallout could have an outsized impact on the global economy, and the conflict is looking more like a protracted slog rather than a brief skirmish. A detached look at events transpiring in Ukraine to date raises skepticism of a lasting cessation of hostilities and the disruptions the war is causing. After one month of fighting, both sides are firmly dug in, and the war is taking shape as a stalemate. As both sides in the conflict take account of their mounting losses, the willingness of either side to make significant concessions on issues that might facilitate an end to the conflict arguably becomes less likely. President Zelenskyy has repeatedly said that Ukraine will not cede territory to Russia as part of a ceasefire or resolution while President Putin has few face-saving options that don’t include annexing parts of Ukraine, so the common ground for a mutually acceptable solution seems rather shaky, while trust has been shattered.

Beyond the horrific human toll and destruction that the war is inflicting, it also threatens to weaken or undermine economic growth beyond the borders of the conflict, particularly if economic sanctions and corporate boycotts on Russia are widened and enforced, which will inflict a toll on the global economy. Roughly one-half of Russia’s $500 billion of annual exports are bought by European countries and are predominantly energy-related. Energy commodities account for 43% of total Russian exports. Economic forecasts for the EU bloc have already been cut for 2022, particularly for the heavy industrial sector, such as automobile production. Europe is far more dependent on trade with Russia than the United States is and more vulnerable to a recession, hence the reluctance of some EU nations to endorse harsh sanctions.

Moreover, whenever hostilities do cease, it’s hard to imagine that normal supply flows of impacted commodities to global markets can resume in short order, or that Russia will be readily readmitted into the community of trading nations as if none of this ever happened. Most foreign policy experts have opined that relations between a Putin-led Russia and Western alliance nations have been deeply damaged by this incursion and will take years to reset. For many nations, the resumption of normal relations with Russia, including trade, will remain a politically sensitive issue even after hostilities cease, while public pressure on corporations to refrain from doing business in or with Russia likely will continue.

Recently there are some perceptible signs that global uncertainties surrounding events in Ukraine combined with the Fed’s signaling of monetary tightening moves to come in 2022 are already impacting the leveraged corporate sector.

Leveraged credit issuance in 1Q22 was down by 50% from a year ago and almost certainly will decrease materially this year compared to 2021. Market yields on leveraged debt remain tolerable for most borrowers but are trending higher and have already exceeded most expectations going into the year. Corporate Chapter 11 filings picked up appreciably in Marchand early April compared to depressed levels in January and February, while default rate forecasts for year-end by S&P and Moody’s have ticked up modestly of late versus late 2021 estimates but remain below average. S&P’s Weakest Link listing, which tallies the number of very low rated issuers (B- or worse) vulnerable to a ratings downgrade in the months ahead, increased by 57 issuers in March – a 29% jump from January and the first monthly increase at all since June 2020, with most of the increase being issuers in Eastern Europe and Russia4.

Admittedly, this scattershot of evidence is hardly a resounding argument that a recession is soon coming or that business conditions are rapidly deteriorating, but it’s still early in this new game, and it does seem safe to say that the environment for corporate restructuring activity likely hit rock bottom in late 2021 to early 2022 and can only pick up momentum from here. A more definitive expectation than that would sound like wishful thinking. On the other hand, financial markets are betting that the economic effects of the war in Ukraine will remain contained and the Fed will thread the needle by bringing inflation under control by year end without tanking the economy — and that seems more like pie in the sky thinking currently.

Exhibit 1 – S&P GSCI Commodity Index vs. S&P 500

Source: Bloomberg

Exhibit 2 – U.S. Producer Price Indexes vs. CPI

Source: FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Footnotes:

3: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/10/business/economy/inflation-expectations.html

4: Global Weakest Links Tally Rises for the First Time Since 2020, S&P Global Ratings Research, March 22, 2022

Published

April 21, 2022

Key Contacts

Key Contacts

Global Chairman of Corporate Finance

Downloads

Most Popular Insights

- Beyond Cost Metrics: Recognizing the True Value of Nuclear Energy

- Finally, Pundits Are Talking About Rising Consumer Loan Delinquencies

- A New Era of Medicaid Reform

- Turning Vision and Strategy Into Action: The Role of Operating Model Design

- The Hidden Risk for Data Centers That No One is Talking About