Inflation Is Raging, Rates Are Rising and Markets Are Reeling. Where Are All the Bankruptcies?

-

June 17, 2022

DownloadsDownload Article

-

The war in Ukraine is now in its fourth month with no visible end in sight to the hostilities and little prospect that the disruptive global economic impacts of the war will dissipate anytime soon. On the contrary, a new $40 billion weapons and aid package to Ukraine by the United States, coupled with 20 other nations pledging further security assistance for Ukraine, and Sweden and Finland applying to join NATO have further ratcheted up tensions between Russia and the Western Alliance nations. With each passing month of death and destruction, it seems increasingly certain that a Putin-led Russia indefinitely will remain an isolated country on the world stage while Ukraine’s economy is decimated.

Beyond U.S.- and EU-imposed sanctions, a growing list of major corporations have chosen to exit their business operations in Russia. Ukraine still has no access to its ports on the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov, forcing it to redirect exports of grains and other products to land routes, thereby greatly reducing export quantities. None of these developments suggests an end is near.

Consequently, the war’s wider effects on the global economy have become entrenched — just ask any farmer that uses fertilizer or any factory owner that uses coal or steel. While the media obsesses over gasoline prices, U.S. natural gas prices are near all-time highs at the prospect of more LNG exports to Europe to compensate for reduced Russian supplies, with economists warning that domestic electricity prices will soar this summer if we experience an unusually hot season. Most global commodity prices are off their multi-year peaks of early March but remain very elevated. They will likely remain higher for longer than anyone imagined earlier in 2022. It has been reported that many energy companies are reducing their price hedging contracts for late 2022 into 2023, a sign that energy producers are increasingly confident that petroleum-based product prices will remain high.1 Putting it all together, any scenario of a short conflict in Ukraine with a limited and transitory global economic impact seems less likely with each passing day, and recent financial market turmoil at least partially reflects a collective recalibration of the duration and impact of that conflict.

The damaging effects of persistent inflation on the U.S. economy became evident last month across the retail sector. Monthly retail sales growth was unexpectedly strong in April compared to a stellar prior-year month in 2021 when stimulus checks had just hit consumers’ bank accounts, an indicator of still-robust consumer demand that all but ensures another 50 bps rate hike from the Federal Reserve in June. However, retail sales growth decelerated and now trails the rate of inflation for consumer goods, meaning that real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) sales growth has become negligible or negative for most retailers. That same week, Walmart, Target and Kohls reported results for 1Q22 that badly missed expectations and lowered earnings guidance for the quarters ahead.2 Despite decent topline growth, these large retailers attributed earnings shortfalls to wage and product inflation, higher distribution and fulfillment costs, and supply chain bottlenecks, all of which depressed operating margins and are expected to persist in the months ahead. Markets did not take these earnings misses lightly. Walmart and Target had their largest two-day price declines since the Black Monday market crash of 1987.

Kohl’s 1Q22 earnings miss was accompanied by significantly lower EPS guidance for 2022, causing some analysts to cool on the prospect of a takeover bid anywhere near the price range previously expected. More broadly, market values of most big-box retailers also were mauled that week. Last month, Amazon also reported disappointing quarterly earnings, and its market value is now back at pre-COVID levels. Overall, May was a tough month for equity markets. Still, a brutal one for the retail sector and other consumer-facing companies, as investors reset their expectations about the impact and duration of inflation on consumer demand and corporate operating performance for the balance of the year. In fact, May’s sell-off of retail stocks was so vicious that it could be signaling the beginning of the end to a two-year spending splurge by consumers since COVID began, as investors apparently have thrown in the towel on the sector. Inflation likely will peak sometime in 2022 but fewer economists now believe it will be tamed by year-end, as several factors contributing to global price spikes have intractable causes beyond the control or influence of government policymakers and central banks, which can only hope to slow demand via rate hikes and monetary contraction. Though more acute in the United States, inflation has become problematic across most developed economies.

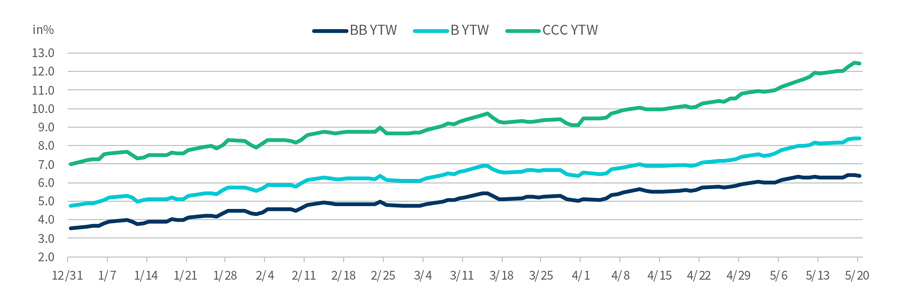

Corporate credit markets were relatively well behaved in early 2022 when equity markets began to sputter but finally have started to reflect the expectation of aggressive Fed rate hikes, sticky inflation and increased credit risk. Speculative-grade corporate bond yields drifted gradually higher to start the year in anticipation of Fed tightening but have widened considerably since early April, with BB-, B- and CCC-rated bond yields moved another 140 bps, 200 bps and 330 bps higher, respectively, since the end of March (Exhibit 1) — considerably more than the 50 bps increase in Treasury note yields in that time.

Where the Heck Are All the Bankruptcies?

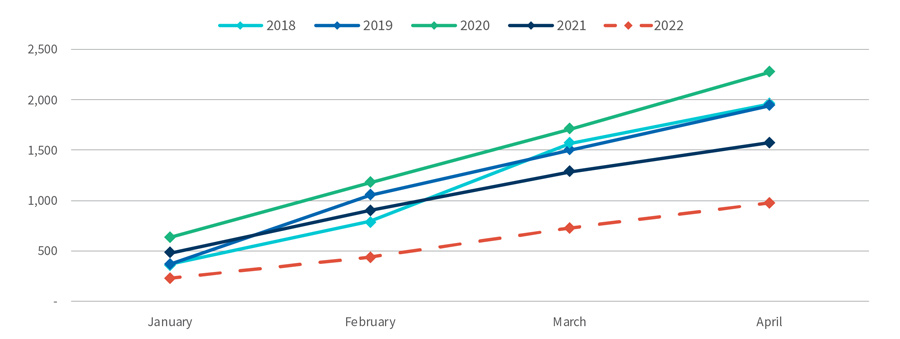

Given the weakening economic backdrop, it seems fair to ask why corporate bankruptcy filings remain so tame nearly halfway through the year. The obvious but unsatisfying answer is that it’s just too soon to expect an appreciable upturn in filings. History says there is a normally a time lag of six to nine months between changes in the economic climate and their impact on restructuring activity. We aren’t quite there yet. However, that explanation is becoming a bit tiresome and, perhaps, less persuasive as the year progresses. Four months into this period of global turmoil, large corporate filings (liabilities at filing greater than $50 million) have increased to levels that can only be considered average at best — around nine or ten per month — with little to suggest we’re on the cusp of a significant upswing. Commercial Chapter 11 filings (all sizes) to date are 40% lower than a year earlier and 50% below pre-Covid filing levels (Exhibit 2), while Reorg First Day reported that YTD 2022 filings through late May (liabilities at filing greater than $10 million) were down 31% from 2021 and approximately 45% from average levels in 2016-2019. Filing activity has picked up since 1Q22, but YTD totals nonetheless are dismal.

Exhibit 1 – Speculative Grade Bond Yields

Source: Credit Suisse and Bloomberg

Exhibit 2 – Cumulative YTD Commercial Chapter 11 Filings

Source: EPIQ Systems

As for the argument that filing activity is depressed because many restructurings are getting done via distressed debt exchanges that avoid the courthouse, that assertion doesn’t fully explain the absence of activity. Distressed exchanges have indeed accounted for an unusually large share of total debt defaults since 2020 (distressed debt exchanges are considered defaults by the rating agencies); however, the speculative-grade default rate remains abysmally low at around 1.4% — little changed since year-end — meaning that the totality of default activity, both in-court and out-of-court, remains depressed.

More discouraging, the usually reliable harbingers of restructuring activity also remain subdued. Distressed debt levels have picked up noticeably from near record lows but remain modest, while S&P’s distressed debt ratio remains near its lowest reading since 2014. Wider speculative-grade bond spreads since year-end imply merely average levels of default activity by early 2023.

Perhaps most concerning, the most recent default rate forecasts from the two preeminent rating agencies expect relatively modest upticks in defaults a year hence, to about 3.0%-3.5% by early 2023 — a doubling from near-historic lows but still below the long-term historical average and nothing resembling default cycle activity.3 These modest default forecasts are expected to prevail domestically and in Europe, where the continent’s proximity to the war and its economic impacts and vulnerability to recession are more acute. Worst yet, S&P’s pessimistic scenario, which includes a U.S. recession, has a projected default rate of just 6.0% by March 2023. However, Moody’s pessimistic scenario default forecast of 13% is much more consistent with historical default rates during a default cycle. It’s hard to fathom exactly why these base-case default rate forecasts are so low. Still, it’s possible that rating agencies have become gun shy about making bold forecasts given how off the mark they were in anticipating and modeling the pandemic-driven default cycle, which materialized quickly but peaked far lower and fizzled out far sooner than they expected.

The most plausible explanation for still-muted restructuring activity is closely tied to leveraged credit market conditions that prevailed in 2020-2021. During this window, higher-risk issuers were able to borrow huge sums at low rates with few strings attached in the way of performance-based maintenance covenants and fewer restrictions on access to and uses of capital (and, often, underlying collateral), giving them financial runway and flexibility to withstand adverse business conditions for an extended period without consequence until liquidity is exhausted, if it comes to that. The list of troubled issuers that undoubtedly would have restructured by now were it not for opportunistic credit market rescues or forbearance by lenders has grown lengthy, and many continue to confront challenges in fixing their businesses.

Traditional safeguards in credit documents that have given lenders or other debtholders the ability to intervene in a troubled credit long before the money runs out often have been weakened or negotiated away by borrowers in recent years. This trend has been in place for a while but now seems like standard practice in leveraged lending circles. Moreover, in those instances when financial covenants have been tripped or events of technical default have occurred since Covid struck, many lenders have been reluctant to exercise their full rights and remedies. They are more inclined to grant a waiver, amend credit documents and collect a fee. That tendency remains in place even after Covid-related business impacts have faded. These developments can either postpone or avert a restructuring event, depending on what companies can accomplish with this breathing room.

Consequently, the current expectation in credit markets may be that many highly leveraged borrowers have sufficient liquidity to ride out whatever adversity comes their way in the next year. Of course, that all depends on the severity and duration of that adversity. Nobody has a clear read on that currently, with forecasts of recession, earnings and inflation being all over the place. We are in uncharted waters today, and nobody should have strong convictions about where the global economy will be a year from now.

Footnotes:

Related Insights

Related Information

Published

June 17, 2022

Key Contacts

Key Contacts

Global Chairman of Corporate Finance

Downloads

Most Popular Insights

- Beyond Cost Metrics: Recognizing the True Value of Nuclear Energy

- Finally, Pundits Are Talking About Rising Consumer Loan Delinquencies

- A New Era of Medicaid Reform

- Turning Vision and Strategy Into Action: The Role of Operating Model Design

- The Hidden Risk for Data Centers That No One is Talking About